EU261: there's no such thing as a free lunch

Note: we started working on this piece in December 2024 when there was a lot of discussion regarding the implementation of a flight cancellation and delay compensation scheme in Australia. We kinda forgot about it, but picked it up again given that the Aviation Industry Ombuds Scheme is due to be released soon.

EU261 is the European Union’s Air Passengers Rights Regulation that is often view as a model for air travel regulation in Australia. A defining and popular feature of EU261 is the compensation that passengers are due in the case of cancelled or delayed flights. Who wouldn’t want to be compensated €600 if your flights was cancelled or delayed?

While this sounds enticing, few consider the unintended consequences of regulations. Simply put, “there’s no such thing as a free lunch”, and fixed cost compensation schemes will likely result in airlines optimising their operations to minimise compensation rather than minimising cancellations and delays. Let’s delve a little deeper into understanding how airlines are likely to respond.

The mechanics of EU261

Since EU261 is often refereed to as a model for compensation schemes, let’s look at how E261 works, and doesn’t work. You may be due compensation of €250. €400 or €600 if your flight is delayed, with the amount depending on the length of flight and delay.

For flights <1,500 km, you are due €250 if you arrive at your final destination more than 2 hours late;

For flights >1,500 km <3,500 km, you are due €400 if you arrive at your final destination more than 3 hours late;

For flights >3,500 km, you are due €600 if you arrive at your final destination more than 4 hours late.

Most proponents of EU261 often forget the words “may be due compensation” since there are a multitude of exemptions where passengers aren’t due compensation due to extraordinary circumstances. These are typically factors outside the airline’s control, like weather or air traffic control problems, but also safety. These exemptions are critical since regulators don’t want to encourage airlines to take unnecessary safety risks to avoid compensation.

As with many things within EU bureaucracy, there is plenty of guidance on how to interpret these exemptions. For example, mechanical faults are included but only pertains to the flight on which the problem occurred. If the flight you are on encounters a mechanical fault them you aren’t due compensation, but a delay to the following flight on the same aircraft would be due compensation. Another example is a strike by airline staff which isn’t considered extraordinary circumstances, but a strike by an airline supplier is.

In addition to delays, passengers may also be due compensation if a flight is cancelled. Again there’s a catch, as you’re only due compensation if you’re notified of the cancellation less than two weeks prior to departure. This means that airlines have carte blanche to cancel flights two weeks in advance.

If notified of cancellation between one and two weeks prior to departure, no compensation is due if passenger is rerouted so that they can depart no more than two hours earlier than scheduled, and arrive no more than four hours later than scheduled. And if notified of cancellation less than one week prior to departure, no compensation is due if passenger is rerouted so that they can depart no more than one hour earlier than scheduled, and arrive no more than two hours later than scheduled.

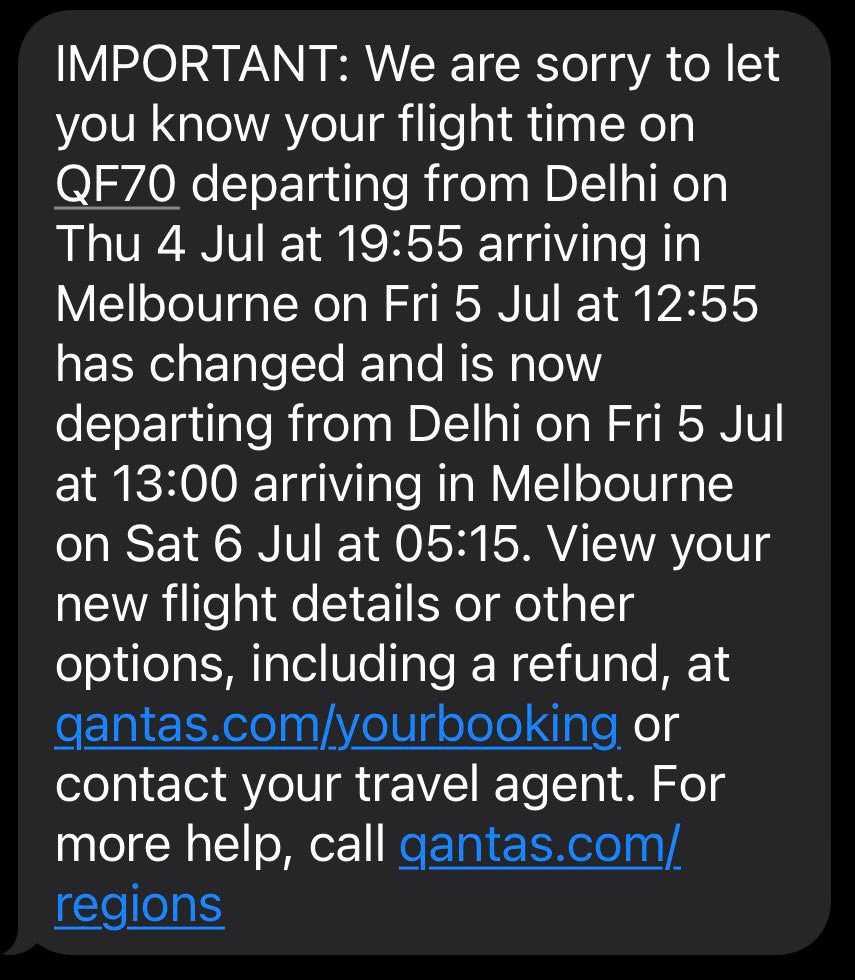

Note that the threshold doesn’t refer to when the flight is cancelled, but when the passenger is notified. Recall that this distinction is important in light of Qantas’s ghost flight case where the ACCC argued that Qantas’s failure wasn’t just the cancellation of the flights but the delay in customer notification.

Any compensation scheme needs cutoffs and thresholds

A key feature of any compensation scheme like EU261 are the cutoffs or thresholds, for example the length of the delay determining if compensation is due or how much compensation is due, or how long in advance a flight is cancelled. Why are these cutoffs and thresholds required?

Firstly, it’s not reasonable to apply the same compensation to a short delay versus a long delay, or a shorter cheaper flight versus a longer more expensive flight. This should be obvious as a 1 hour delay just isn’t the same as a 12 hour delay, nor is a 1 hour delay to a 1 hour domestic flight and a 1 hour delay to a 16 hour ultra long haul flight.

However, the cutoffs are based on discrete thresholds and ultimately arbitrary. A flight that covers a distance of 1,499km that is delayed 3 hours gets €250, but a 1,501km flight that is delayed 3 hours gets €400. Similarly, notification of a flight cancellation 15 days out isn’t due compensation, while 13 days out is. Once again, this two week line in the sand is arbitrary, but it has to be drawn somewhere.

Gaming the system #1: exploiting 2 week threshold

Air travel with legacy airlines can be booked up to 11 months in advance. That’s the typical timeline when airline reservations systems (at least legacy GDS) make inventory available for sale to the public. Some airlines, particularly low cost airlines have significantly shorter timelines for inventory availability.

Advanced reservations has benefits for both airlines and customers. It allows airlines to increase cash flow but also gauge demand, allowing time to adjust capacity to meet market demand. It also gives customers greater flexibility and choice, and most importantly, cheaper fares.

Hypothetical, let’s consider what would happen if airlines had to pay compensation for any cancellation, irrespective of how far in advance the flight is cancelled. This would increase their costs of making inventory available in advance and/or reduce their benefit of making inventory available far in advance.

Ultimately, it increases the risk of making inventory available in advance and their likely response will be to shorten the advance period, reduce capacity made available in advance including the availability of cheaper fares (since the relative risk is higher due to fixed cost nature of the compensation), or dripping capacity into the market. Furthermore, they might disproportionately apply these to flights that may be at higher relative risk, particularly lower yielding flights (again, due to fixed cost nature of the compensation). Any combination of these would be a poor outcome for passengers.

So imposing a cutoff is necessary but this is only the first part of the problem. Once a cutoff is imposed the arbitrary nature of the threshold generates incentives for airlines that they can (and will) build optimisation models around. Here’s a typical example of what might happen and it’s actually a real-world example that we encountered a few years ago:

We booked a flight on 31 December 2023 for travel on 24 July 2024 on Wizz Air. The flight was booked 7 months in advance. The itinerary was Santorini to Tel Aviv, departing 10:35am, arriving 12:25pm; costing €497.98 for two passengers.

On 6 May 2024, Wizz Air notified us that our original flight has been cancelled. They offer us an alternative flight on 22 July 2024 (departing 6:45pm). This is already 4 months after we made the reservations, so obviously we’ve already made other other reservations including other flights and accomodation, making leaving two days earlier not at all viable.

So we have to opt for the full refund and make our own alternative arrangements. But since 4 months have passed and just 2.5 months remaining before the flight, alternative options are likely to be more expensive.

Our best option was to rebook on Aegean Airlines, departing on 24 July 2024, departing 2:55pm, arriving 6:50pm, and flighting via Athens. This trip takes us a little longer and costs us €596.80.

So we’re out of pocket €98.82 and taken more than double the flight time, but because we’ve been notified more than 2 weeks in advance we’re not due any compensation. In this specific case they actually notified us 10 weeks in advance (nice of them to do so), and highlights a key point, that thresholds are arbitrary. A line in the sand has to be drawn somewhere, whether that be 2 weeks, less than 2 weeks, or more than 2 weeks.

Wherever these thresholds are drawn and whatever the penalties (i.e. compensation), they just become the parameters around which airlines make optimising decisions. Increasing 2 weeks to 2 months will just push airlines to cancel flights earlier. This will benefit passengers on flights that are cancelled but will also increase the risk for airlines and result in other unintended consequences.

But it gets worse: we started with the lease egregious example! The next examples show how it can get worse for passengers as airlines can (and will) find methods to minimise compensation due from delays.

Gaming the system #2: distribute delays

While the goal of a compensation policy like EU261 is to reduce or eliminate cancellations or delays, the use of compensation as a tool will actually result in airlines optimising their operations to minimise compensation. Once again, it’s about discrete thresholds. Let’s take the EU261 thresholds and apply them to the Australian domestic market in a practical example:

Airline X has a Melbourne-Sydney sector scheduled to depart Melbourne at 10:00am, with a scheduled arrival time in Sydney of 11:30am. It’s due to be operated by an aircraft flying into Melbourne from Brisbane with a scheduled arrive in Melbourne of 9:00am.

The airline’s operations centre learns that the inbound from Brisbane has been delayed 3 hours due to a mechanical fault. While the Brisbane-Melbourne flight isn’t due any compensation as its delay is due to a mechanical fault, this protection doesn’t extend to the following sector. However, it results in the delay of the Melbourne-Sydney departure from 10:00am to 1:00pm, with a new estimated arrival at 2:30pm instead of 11:30am.

The resulting 3 hour arrival delay would result in passengers being due A$450 (€250) in compensation. Airline X will want to avoid paying this compensation. The goal isn’t to avoid the delay, but rather avoid the A$450 in compensation!

So the operations centre starts looking for an alternate aircraft. Can they cannibalise an aircraft from another flight? Importantly, they’re not looking for an aircraft that can depart Melbourne at 10:00am, but anytime up to 12:00pm, as this will mean arriving in Sydney by by 1:30pm. As long as they arrive in Sydney by 1:30pm they’ll avoid paying compensation which is only becomes due if the flight is delayed by more than 2 hours.

The operations centre find a Melbourne-Adelaide that’s scheduled to depart Melbourne at 12:00pm, arriving in Adelaide at 12:40pm. The airline takes this aircraft and transfers it to the Melbourne-Sydney flight. The flight departs Melbourne at 12:00pm and arrives in Sydney at 1:30pm. It’s arrived 2 hours late instead of 3 hours late. This is a better outcome for the Sydney bound passengers, but more importantly, Airline X doesn’t have to pay compensation.

But what about the Melbourne-Adelaide flight? It now takes the aircraft originally scheduled for Melbourne-Sydney aircraft that arrives from Brisbane at 12:00pm. It departs Melbourne at 1:00pm and arrives in Adelaide at 1:40pm, with a 1 hour delay.

So instead instead of 180 passengers delayed 3 hours (540 hours), we have 180 passengers delayed 2 hours (360 hours) and another 180 delayed 1 hour (180 hours) (360 + 180 = 540).

Airline X has taken a 3 hour delay on a single flight and redistributed that single 3 hour delay across two different flights of 2 and 1 hour, respectively. By redistributing the delay they’ve managed to avoid paying compensation. The threat of compensation hasn’t removed the delay but generated an incentive for the airline to optimise their tactical plan to eliminate paying compensation. We can debates which is better or worse, however it’s entirely subjective!

EU261 was meant to reduce delays, however it inadvertently incentivises airlines to minimise compensation rather than delays. It’s reduced the delay for some passengers, but introduced a delay for passengers that otherwise wouldn’t have been delayed at all. In effect, it socialises the externalities of the delays.

A secondary and even more egregious consequence is that once a flight (with no recovery options) is delayed beyond 2 hours, the airline’s incentive switches once again. Recall that the airline pays the same compensation whether the flight is delayed 3 or 8 hours. If the airline has other flights with a risk of delay exceeding 2 hours it can manipulate operational schedules - just like we showed in the example - and pack the additional delays into the one flight that’s already due compensation. In effect, this flight now becomes the “donor flight” as the airline has an incentive to delay this flight further to eliminate >2 hour delays on other flights in the network.

For example, it can take the aircraft from the original 2+ hour delay and utilise it to avoid a 2+ hour delay elsewhere. This’ll progressively increase the delay on the donor flight. So one unlucky flight might see its delay increased from 3 hours to 8 hours to eliminate compensation due on other flights. Again, this results in concentrating delays and is objectively bad!

Gaming the system #3: overbooking

Another unintended consequence is how it gives airlines full cost transparency for overbooking, a practice where an airline sells more seats on a particular flight than there are seats available. There are several reasons why airlines overbook flights (explained below) and we’re not defending the practice of overbooking, rather considering how EU261 affects it. This is importance since the genesis of EU261 was to force airlines to pay compensation to passengers in the event of denied boarding (the term EU261 uses).

Why do airlines overbook flights?

Revenue maximisation:

Let’s assume an airline sells all the seats on a particular flight for fares between €100 and €300 each. The flight is ostensibly sold out, but on the day a customer walks up to the counter and is willing to pay €500 to be on that flight. Despite not having a seat available, the airline goes ahead and sells the customer a ticket for €500.

They’ll now have to remove a ticketed passenger from the flight to make space. If they remove someone who paid €100 they’ll make a gain of €400, while removing someone who paid €300 will result in a gain of €200. Thus, as long as the oversold ticket is more expensive than the passenger who is removed, the airline gains.

It’s even become common practice in the US for airlines to offer passengers inducements to voluntarily take a later flight. As long as this inducement costs less than €200 it’ll result in a net gain and very likely result in two happy customers!

Risk of missed connections and no shows:

Some airlines operate hub-and-spoke models that connect passengers from one flight to another. Some inbound passengers will arrive late and miss their connections. Alternatively, some passengers just don’t turn up, including those with flexible tickets. Missed connections and no-shows cost airlines lost revenue when seats go empty.

This leads them to selling more tickets with the expectation of some missed connections and no-shows. Airlines have pretty good data to estimate the number of passengers that are likely to miss a flight. In some cases, it can be quite granular with flight, day and seasonal specific estimates. The challenge comes when the number of missed connections or no-shows is less than expected, leading to oversold flights.

So now if a passenger is denied boarding due to overbooking, then the airline must pay the passenger €250 if they are unable to get the passenger to their destination on another flight that’ll arrive at their destination within 2 hours of the originally scheduled arrival time.

But here’s the kicker: now that the airline knows their penalty they also know the marginal revenue required to overbook!

In the example, the passenger that bought the overbooked ticket on the day of the flight paid €500, replacing a passenger on a cheap ticket that cost €100. The airline’s marginal revenue was €400. But the airline now knows that as long as the marginal revenue is greater than the €250 compensation then they’re in the money and a marginal profit of €150 (€400 less €250). Thus, as long as the marginal revenue exceeds compensation, the compensation generates incentives for the airline to overbook more, not less!

The problem isn’t regulation per se, but rather that airlines must pay compensation. And since compensation is fixed, and this fixed any potential cost for the airline. While the example of overbooking appears trivial in comparison to the previous two examples, it highlights how better regulation without compensation is likely to generate better outcomes. But what is this alternative regulatory option?

It’s actually quite simple, just require that a confirmed ticket guarantees a seat. i.e. an airline must seat all ticketed passengers! And if they can’t then they must find a willing volunteer to give up their seat. Willing buyer, willing seller!

Rather than fix compensation, airlines would have to offer an inducement to a passenger or several passengers to give up their seat. Instead of fixing compensation, they’ll have to pay what people are willing to accept. For example, they’ll probably have to pay a lot more to get passengers to give up their seat at 5pm on a Friday afternoon than they would at 11am on a Sunday. They’d also have to pay successively larger amounts for more passengers.

The opportunity cost for every passenger is different, and may also vary by time or day of the week. So why should the compensation be the same? Forcing an airline to find a willing volunteer ensures that overbooking is properly priced rather than being priced by a bureaucrat in Brussels or Canberra.

And if an airline ends up having to pay a lot of money, exceeding their marginal revenue, then that’s their problem. If that happens too often and costs them too much money they’ll adjust their overbooking policies accordingly. Ultimately, it’ll force airlines to price risk accordingly, rather than fixing their risk based on an arbitrary price.

Concluding thoughts

No doubt, some will read this and label us as (airline) apologists. Australian airlines have seen their reputations go downhill in recent years and they’ve become media cannon fodder. High rates of cancelled and delayed flights have added fuel to the fire, especially in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. We recognise the displeasure the public has with the industry and how this makes compensation policies like EU261 popular. Such policies will penalise the perpetrators and give the aggrieved a sense of justice. We get it and we understand it!

But what is the purpose of compensation policies like EU261? Is it an archaic sense of justice where perpetrators of bad things must face penalties to bring about justice for the victims? Let’s be frank, this isn’t a violent crime or property crime. It’s a cancelled or delayed flight.

Instead of being apologists, we’re simply showing how compensation policies aren’t likely to be effective at reducing flight cancellations or delays, or even reducing the length of those delays. Airlines are cunning and they’ll respond to the incentives in front of them. The challenge for regulators is that compensation policies generate incentives for airlines to minimise compensation, not minimise cancellations and delays.

We showed some mechanisms they’ll use to game the system, for example changing the distribution of delays rather than the total quantity of delays. So instead of only some passengers being delayed, a larger number of passengers who would otherwise not have been delayed will now have to be delayed in order to minimise compensation. Alternatively, passengers who are due compensation may experience longer delays than they otherwise would have to limit compensation having to be paid to other passengers. We also showed how the application of compensation to overbooking might actually increase overbooking as fixed compensation provides transparency of the cost of overbooking for airlines.

So what should regulators do? It’s rich to critique what they shouldn’t do without actually saying what they should do! Firstly, policy makers would be better advised to conduct a thorough and comprehensive assessments regarding the cause of cancellations and delays. This seems like we’re punting, but without understanding the cause and variance of cancellations and delays, it’s difficult to design solutions to reduce them.

Secondly, what about introducing more graduations into the system, as suggested during discussions on social media? There’s some validity to this, but this introduces even more (arbitrary) discrete thresholds with fixed cost parameters for airlines to optimise around. It misses the point that a compensation based systems will always have an objective function to minimise penalties, not improve underlying behaviours.

Thirdly, require transparency. Some cancellations and delays are inevitable or unavoidable, whether they’re a result of mechanical faults or poor weather. Others aren’t inevitable or unavoidable and the responsibility of airlines, whether that be due to poor planning or execution. However, we very little understanding of cancellations and delays in Australia.

For example, BITRE data on cancellations and delays just tells us the percentage of flights cancelled or delays by airline and route. Inexplicably, it doesn’t tell us anything about the length of delay and a 16 minute delay is counted the same as an 8 hour delay. It also doesn’t tell us about the day of the week but more importantly it says nothing about cause of delay and thus who bares responsibility! This piles the responsibility on airlines and absolves the rest of the supply chain of responsibility, whether that be weather, airport congestion or ATC staffing shortages.

The other side of transparency is not about regulation, but airlines themselves. Most airlines don’t have a culture of transparency when it comes to cancellations and delays. Often they don’t say anything while at other times they’ll say vague things like "your flight is delayed by weather".

Why don't more they communicate more transparently? Do they think people don't want to know, don’t care or can't understand? We’re not suggesting a sinister motive, rather just risk aversion, but we argue that transparency builds trust!

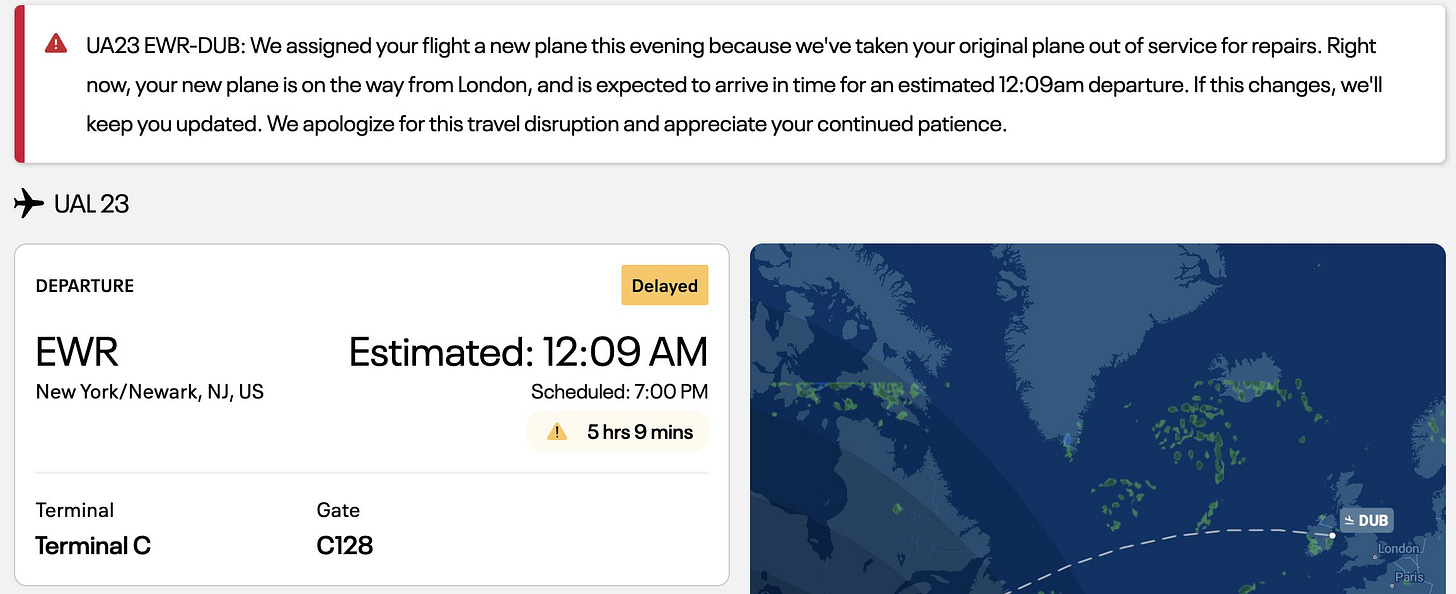

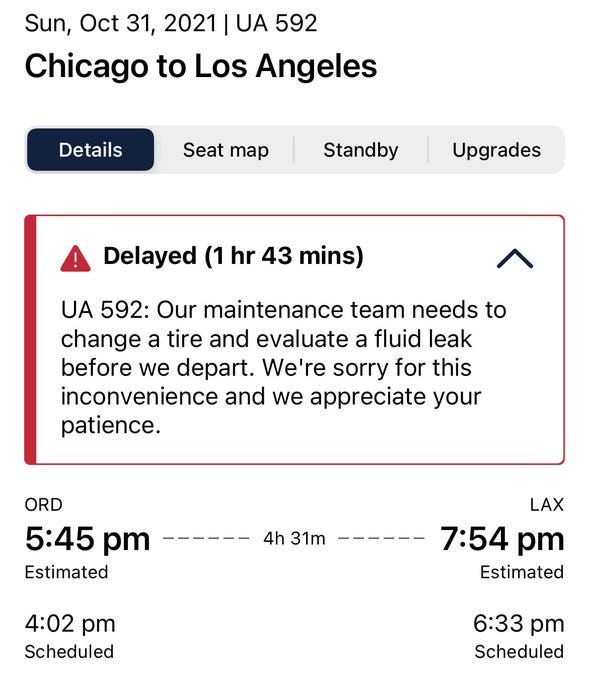

Since 2018, United Airlines have been taking a very different approach with a narrative of "every flight has a story". They argue that it reinforces a culture of transparency and builds trust. In many cases, they’re providing mundane details but it pushes back against the commoditisation of air travel, just a little.

It's the mundaneness that is so brilliant! It would be very easy to just come across with sophistry (clearly why we shouldn't be allowed to write them!!!). It's got to be specific enough not to seem generic and vague, but mundane enough to avoid appearance of sophistry!

Transparency won’t solve the problem, but it also shows that arbitrary thresholds and penalties will do the same. It’ll give a handful of people a good story to tell their mates at the pub about how they got a few hundred bucks off Virgin or Qantas for a delayed flight, while all their other mates complain they didn’t get compensation despite their flights being delayed.

Meanwhile, the number of cancelled and delayed flights hasn’t declined, and we can’t even say if the length of delays has changed, or whether there have been any changes in the reasons for those delays.

But it would’ve created a whole new bureaucracy to implement it, including dodgy ambulance chasers offering their help getting compensation. Policy makers will pat themselves on the back for implementing policies to help the public, despite it not really doing so. Welcome to AU261!

Doesn't that shift the gamification from the airlines to the consumer. I'd start booking on seats which I expect I can give up for high compensation.