Implications of the Australian government’s decision to block additional frequencies for Qatar Airways

On 10 July 2023, the Minister for Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Local Government, Catherine King, rejected Qatar Airways’s (QR) request for permission to operate 28 additional weekly flights to Australia. The decision has been widely criticised for stifling competition and taking a protectionist approach, ostensibly protecting the interests of Qantas Airways (QF). QF have confirmed reports that they wrote to the Minister to note their objections and this has added to the increasing criticism that QF have faced in the media and on social media in recent years.

The decision to reject QR’s request has received far more attention that a similar denial for Turkish Airline’s request for additional frequencies to facilitate their entry to the Australian market with daily flights to Sydney (SYD) and Melbourne (MEL). One might speculate as to why the QR decision has received so much more attention, but that is not the focus of this analysis.

While the decision to reject QR‘s application is not likely in the public interest, the arguments that QF put forward have been widely ignored in the public discourse. The purpose of this analysis it to evaluate the impact of the decision in the context of QR’s Australian operations and review the impact that approving QR‘s request may have had on the market. Furthermore, it will evaluate the arguments put forward by various stakeholders, both for and against.

Background and context

International flights operate under a global system of bilateral and multilateral agreements. Before an airline can fly to a foreign country, the governments of both countries need to come to an agreement how flights between the countries are managed. Several different types of legal instruments are used including a Bilateral Air Services Agreements or a Memorandum of Understanding. These cover many areas, including the number of flights airlines can operate, the number of passengers they can carry, the airports they can fly to, and the countries that they may stop over in along the way or continue onto. They also cover a range of technical issues including safety standards and taxes. Generally, they are based on reciprocity, meaning that the countries treat each other equally, and the access granted to one country is in return for the same access granted by the other country.

The agreement between Australia and Qatar establishes a limited number of frequencies (i.e., flights per week), and limits the destinations in Australia that the airlines can fly to and from. The same limits apply to both countries and the agreement is not in any way unusual. At present, the agreement allows the following for both countries (see Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts’s Register of Register of available capacity for Australian international airlines—8 September 2023):

28 flights per week between Doha (DOH) and SYD, MEL, Brisbane (BNE), or Perth (PER), with no limitations of aircraft size;

7 more flights per week between DOH and SYD, MEL, BNE, or PER provided the flight operates via another point in Australia other than SYD, MEL, BNE, or PER (e.g., Adelaide (ADL), Canberra (CBR), Cairns (CNS), Darwin (DRW), Gold Coast (OOL)), or beyond to any other point in Australia (again other than SYD, MEL, BNE, or PER). For example, this additional flight must fly DOH–ADL–MEL (via) or fly DOH–SYD–CBR (beyond);

In addition to these 35 weekly flights, there are unlimited frequencies with any aircraft type to or from any point in Australia other SYD, MEL, BNE, or PER, meaning that they have unlimited capacity to for direct flights to ADL, CBR, CNS, DRW, OOL, etc.

At present, QR are utilising all frequencies in the first two points, as well as one additional daily frequency under point 3. No Australian airlines are utilising any of their potential allocations. It has also been revised frequently, with the main block (point 1) having increased from 14 to 21 in September 2015, and 21 to 28 frequencies in (possibly February) 2022.

However, this capacity is significantly smaller than competing stop-over carriers like Emirates Airline (EK) and Singapore Airlines (SQ) have, however this is likely a function of QR’s later entry to Australia, and their more recent growth. Australia and Singapore have an open skies agreement, with no limits on the number of frequencies or restrictions on airports. Australia and the United Arab Emirates have a similarly bilateral to the Qatar bilateral, however allowing 154 weekly services to SYD, MEL, BNE, or PER with no limitations on aircraft size, and 21 additional weekly services if they operate via another point or point beyond SYD, MEL, BNE, or PER.

The request by QR was to increase the number of frequencies available in the main block (point 1) by an addition 21 or 28 frequencies per week. Some reports claim this to be 21, while others indicate this to be 28. The confusion may arise from the treatment of existing flights in block 2 shifting to block 1.

Qatar Airways’s utilisation and capacity

The bilateral limits the frequencies that QR may operate but does not place any limits on aircraft size. Given the significant variation in QR’s fleet, with aircraft varying from the 254 seats B788 to the 517 seat A380 (see Table 1). This provides them with significant capacity flexibility. For example, 28 weekly A380 flights would provide 14,476 seats per week in each direction, more than double what the same schedule could provide flying the smaller B788 (7,112 weekly seats).

At present, QR operate 42 weekly flights to Australia, including daily flights to SYD, MEL, PER, and BNE exploiting the 28 weekly frequencies allocated in block 1, an additional daily flight to MEL (flying onto ADL) allocated under block 2, and a daily flight to ADL allocated under block 3. Flights to SYD and PER are operated with an A380, MEL (including the additional flight) and BNE are operated with a B77W, and the direct ADL service with an A359, providing 16,653 seats per week in each direction (Table 2).

This fully utilises the allocation under blocks 1 and 2 (there are no limitations on block 3). While QR are utilising all their allocated frequencies, they are not maximum their capacity since they are not utilising their largest aircraft on all routes. For example, increasing BNE or either of the MEL flights from a B77W to A380 would add an additional 1,141 seats per week in each direction.

The additional daily flight to MEL operated under the block 2 allocation has come in for recent scrutiny and even ridicule. It continued onto ADL which QR already operate a non-stop service to under their unlimited frequencies under block 3. Furthermore, it operates with a rather peculiar schedule (Table 3) with a 6-hour layover in MEL on the outbound! While the layover on the return leg is more reasonable it seems unlikely that passengers would voluntarily book this flight (it is bookable) when a non-stop service is available. One might argue that the purpose and spirit of the bilateral is to encourage airlines to service secondary cities like ADL, however QR may simply be exploiting a poorly conceived structure.

Clearly QR 909/989 is flown to exploit the 5th additional daily frequency, by flying only ADL after MEL. The absurdly long layover in MEL shows that QR have little interest in carrying passengers onwards to ADL. While the flight is bookable (i.e., DOH to ADL) this is likely only available to ensure compliance with the bilateral. QR’s schedule, including the ground times are likely optimised for crew scheduling and timing of departure and arrival times in DOH to align to QR’s connecting banks.

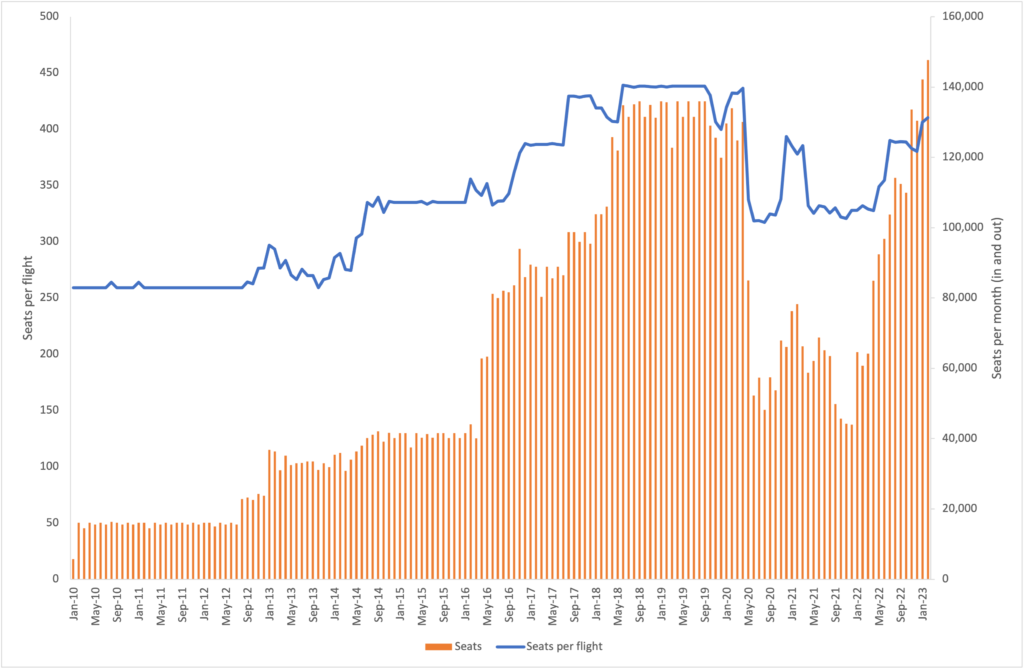

QR’s capacity to Australia has grown remarkably since their entry to Australia in 2010. Starting with daily flights to MEL, adding PER in 2012, followed by SYD and ADL in 2016. Capacity to MEL and SYD increased significantly in 2017 and 2018, respectively (Figure 1). Capacity increases have been supported by additional frequencies and increases in gauge. The increase in gauge is notable by tracking the average seats per flight alongside total capacity over time (Figure 2). Notably, while average seats per flight have increased as capacity has returned following the COVID-19 pandemic, the average gauge is still below pre-pandemic levels.

How much capacity will the additional frequencies add?

There have been claims that the additional frequencies would add dramatic capacity to the market. These claims have gone as far as QR’s Australian partner Virgin Australia (VA) arguing that the additional frequencies would have added a million seats a year to the market and reduced prices by 40%. This is a rather wild exaggeration. Let’s consider …

VA’s claim presumes that the additional 21 frequencies (applied as an additional daily frequency to SYD, BNE and PER) simply scale up existing flights at the same gauge. For example, this would increase daily A380 flights to SYD and PER to twice daily A380 flights, and daily B77W flights to BNE to twice daily B77W flights (Table 4).

This is an overly optimistic assumption. Firstly, it’s unlikely that the additional frequencies would remain at the same gauge (at least to all destinations), but secondly there is a strong case to be made that they may decrease the gauge of both exiting and additional frequencies. Network carriers strongly prefer to operate routes at higher frequency, often on smaller aircraft, rather than maximising capacity on a smaller number of frequencies with larger aircraft. Even though more flights on a smaller gauge has a higher fixed cost than a smaller number of flights on larger aircraft (assuming the same total capacity), higher frequency generates higher yields and can be more profitable. As routes get longer the trade-off between frequency and capacity declines.

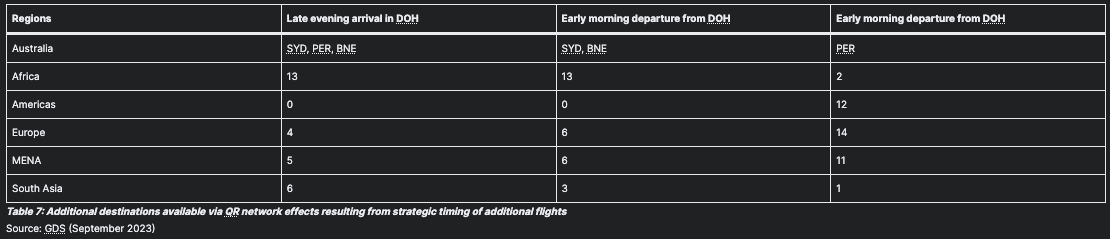

For example, at present SQ operate 3 daily flights between SIN and BNE, operating a 303 seat A350-900, providing 909 seats per day. However, the same capacity could be operated by a twice daily A380 (942 seats per day), likely at lower cost. Distributing the three flights across the day (Table 5) allows SQ to generate higher yields, increasing total revenue by more than the additional costs of operating the third daily flight. The higher yields are generated through several benefits, including a competitive advantage over lower frequency operators, but importantly by providing a greater number of connecting options at SIN (e.g., to other destinations in the network that are operates at low frequency). For example, only SQ 245 connects to SQ’s flights to Johannesburg (JNB) and Cape Town (CPT) (SQ 236 departing SIN at 1:30am), while only SQ 245 connects to the return flight from JNB and CPT to SIN (SQ 479 arriving SIN at 6:10am), despite SQ 236 not the turnaround flights from SQ 245. While SQ 236 will connect well to long haul destinations to the west of SIN, it does not provide good connecting options to the Asia-Pacific region (APAC) (SQ 246 is most efficient). And similarly, while SQ 245 will carry connections from those long-haul destinations to the west of SIN, it is not efficient carrying connecting traffic from APAC countries (SQ 255 and 235 more efficient). Not only does the higher frequency schedule generate greater yields by providing customers more options and a strategic advantage over lower frequency operations, but it allows SQ customers accesses a greater number of connection options at SIN.

The degree to which carriers organise connecting options around connecting banks (i.e., highly concentrated patterns of inbound flights followed by highly concentrated patterns of outbound flights) may depend on several factors. Carriers like QF do not focus on banks since they connect a relatively large number of passengers to a relatively small number of destinations (e.g., a larger proportion of connecting passengers at SYD are likely connecting to MEL and BNE). QR’s network is strongly focused on connecting banks. This is somewhat evident from their relatively high number of destinations served relative to capacity. For example, QR fly to 173 destinations compared to EK’s 133, despite having a smaller fleet and carrying fewer passengers.

QR’s Australian schedule would be benefited by frequency rather than capacity, and this is already in QR’s existing Australian network (Table 6). For example, the two MEL flights depart DOH at very different times, the earlier at 3:05am and the later at 8:25pm. It’s noticeable that PER, SYD, and BNE flights are split between the banks, with PER departing at a similar time to the earlier MEL departure, and BNE and SYD at a similar time to the later MEL departure. On the return, departure times ex-Australia are less important than the arrival times in DOH that are timed to connect into the connecting banks. Again, the two MEL flights arrive at very different times, first in the morning bank at 4:30am and the later in the late evening bank at 10:50pm. All other Australian departures are timed for arrival into the morning bank at DOH.

QR’s additional flight will be timed to connect to and from a second connecting bank in DOH, similar to the second existing MEL flight. For example, we can expect the second SYD and BNE flights to depart DOH between 2:00am and 3:00am, arriving at BNE and SYD in the late evening (although the SYD flight may run into some curfew issues requiring some creative or aggressive scheduling, possibly with long ground times in SYD like EK’s SYD operation). The return departure will likely be timed for afternoon (like QR 989 MEL–DOH) requiring significant ground time at BNE and SYD. These network effects are incredibly important. A second daily SYD, PER, or BNE flight departing from Australia timed to arrive at DOH in the late evening (rather than the existing early morning arrival) will open benefit connections to Africa more than other regions (and the same for the return flight) (Table 7). This is in addition to additional capacity to existing destinations through multiple frequencies. For example, 22 European destinations are available during both banks on the outbound, and 20 on the return.

There is no guarantee that QR will maintain the gauge of either the existing or additional flights when adding frequencies. As previously shown in Table 4, if the additional capacity maintained the same gauge, 21 additional frequencies to SYD, BNE and PER would add 9,716 seats per week, an increase of 58%. However, an adjustment of gauge is likely on some, if not all routes. For example, instead of increasing from a daily to twice daily A380 to PER, they may substitute with a smaller B77W on both flights. Instead of capacity increasing by 3,619 seats per week, the increase will be limited to 1,337 seats per week (Table 8a and 8b). A similar strategy may be applied to SYD (A380 to B77W) and BNE (B77W to A359). Furthermore, not all 21 frequencies may be incremental increases and 7 may be used to replace the existing second daily MEL flight (operated under the block 2 allocation) with a non-stop flight (i.e., removing the ADL leg). If this were to replace the assumed second daily PER frequency, this may limit capacity increases to SYD and BNE only.

The net increase in annual capacity will be substantially lower than VA’s claim of 1 million additional seats. The most conservative strategy and assumptions may add as few as 293,384 seats annually, but a more pragmatic strategy and assumptions may still add less than half of VA’s estimate. One might argue that VA’s lobbying is as cynical as QF’s. Obviously, these estimates are speculative and we have no knowledge regarding how QR might apply new frequencies or adjust gauge, however it’s also speculative – and somewhat cynical – to assume that they would simply add capacity at the existing gauge. Arguably, adding frequencies at the existing gauge is the least likely scenario since it would appear inconsistent with QR’s existing strategy of not maximising capacity of existing frequencies to MEL and BNE.

Conclusions

QR have significantly increased capacity to Australia over the last decade through a combination of increased frequencies and increase of gauge.

QR fully utilise the frequencies available to them under the bilateral agreements between Australia and Qatar, including the

creative and cynicaluse of frequencies designed to attract capacity to secondary cities in Australia.While frequencies are fully utilised, QR are still able to increase capacity through increasing gauge of existing flights to MEL and/or BNE; furthermore; additional capacity is available to other secondary cities.

QR’s strategy focuses on increasing capacity to Australia while also increasing frequency which would enable benefit QR’s operating by increasing the number of connecting options in DOH allowing them to compete more effectively with other stop-over carriers like EK and SQ.

The impact of the additional frequencies on increasing capacity and the impact on the market are likely significantly overstated, however the increase in capacity would be dependent on QR’s strategy of how to allocate frequencies and likely adjustment of gauge on existing and additional frequencies.

Additional follow-up analyses will consider a secondary question: who stands to benefit from the decision to block? Much of the public discourse has focused on QF’s lobbying and the narrative from the government that the decision explicitly protects QF from unfair competition. However, as the next analysis will highlight, QF‘s market share on competing routes (with QR) is incomparably small compared to QR and other stopover carriers.