Surprised or not surprised? Qantas schedules A380 flights to Johannesburg in 2024

Qantas recently announced the deployment of the A380 on flights between Sydney (SYD) and Johannesburg (JNB) effective 7 July 2024. The move surprised many observers who perceived it as a significant upgrade from the B789-9, with the 485 seat A380 carrying significantly more passengers than the 236 seat B787-9. While it is a significant increase in gauge this analysis shows that when combined with Qantas’s careful capacity management and the indefinite absence of South African Airways (SAA) from Australia, the net increase in capacity is limited, and may even result in a net reduction in capacity. This analysis considers the history of routes between Australia and South Africa, analysing capacity, gauge, network as well as important competitive and strategic considerations.

History of Qantas and SAA operations between Australia and South Africa

Qantas and SAA both have a long history flying between Australia and South Africa, beginning in the 1940s and 1950s. Following the political isolation of South Africa and the implementation of sanctions against the Apartheid government, Qantas suspended flights to South Africa in 1976. These flights were eventually replaced with services to neighbouring Harare (HRE) in Zimbabwe in 1982. SAA continued to serve Australia until 1987 before landing rights in Australia were revoked. After the fall of Apartheid, Qantas and SAA returned to operate routes between Australia and South Africa in 1992. Qantas maintained a dual operation to both South Africa and Zimbabwe for an additional 18 months, exiting Zimbabwe altogether in 1993.

Since the early 1990s, Qantas and SAA have operated various route configurations. Initially, Qantas and SAA both operated JNB–Perth(PER)–SYD (with SAA enjoying local traffic rights on the PER–SYD sector for continuing passengers). In 2000, Qantas and SAA entered a codeshare partnership, later becoming a joint venture of sorts. The partnership resulted in both airlines ceasing the one-stop flights, instead replacing them with non-stop services, with SAA operating JNB–PER and Qantas operating SYD–JNB. Notably, this was approved by the International Air Services Commission (IASC) on the basis that the arrangement was likely to contribute to a net increase in capacity with both airlines increasing frequency over time. Qantas and SAA both responded by increasing their respective services from 4x to 5x weekly soon thereafter.

In addition to codeshare capacity on each others’ non-stop flights, the partnership also allowed both airlines to offer onward connections via each other’s domestic and regional networks. For example, SAA was able to access Qantas‘s entire domestic network from both PER and SYD, with amongst others, important connections to Melbourne (MEL), Brisbane (BNE) and Adelaide (ADL), while Qantas was able to access SAA‘s entire domestic and regional network from JNB. This included domestic connections to Cape Town (CPT) and Durban (DUR), but also to regional centres (e.g., the previously served HRE). The increased capacity and network access provided significant public benefit alongside shorter flight times.

The partnership was periodically reviewed and extended by IASC with various conditions, however scrutiny from the IASC and the ACCC increased over time. Increasingly shorter extensions with more stringent conditions sent a signal that the IASC would cease to extend the approval at some point. The public benefit was dependent on increasing capacity by both Qantas and SAA, which was limited by stronger competition from stopover carriers. Furthermore, both airlines had alternatives to provide domestic and/or regional feed with the emergence of Comair, the now defunct British Airways franchisee in South Africa, and Virgin Australia on the Australian end. Qantas and SAA went their seperate ways and ended their partnership in 2014, although it is highly likely that this was in anticipation of the IASC rejecting the next reauthorisation.

Qantas and SAA maintained the split operation with SAA serving PER and Qantas serving SYD. SAA entered codeshare partnerships with Virgin and Air New Zealand, while Qantas entered into a codeshare partnership with Comair. Virgin had their own foray into South Africa in 2010, flying MEL–JNB for 12 months between March 2010 and February 2011. The operation was short lived despite Virgin achieving higher load factors than Qantas and SAA, and attaining a very respectable market share of 15% (17% of seat capacity) on direct services.

At the time, Virgin complained of several operational challenges including Australia’s conservative approach to ETOPS operations which placed an 180 minute limit on he twin-engined B777-300ER they operated on the route, requiring a significant diversions from optimal routings, increasing flight time and fuel burn. Notably, Australia has since modernised EDTO (replacing ETOPS) regulations allowing a more generous 330 minute limit (see Figure 1). Furthermore, the B777 was also subject to payload restrictions on the eastbound sector due to JNB’s hot-and-high performance challenges (due to JNB‘s altitude of 5,558ft above mean sea level). Meanwhile, Qantas and SAA were operating four-engined aircraft that were not subject to the same operational and performance limitations.

Capacity between Australia and South Africa in the post-Apartheid period

Capacity between Australia and South Africa is shared between direct services and a range of stopover carriers. Data presented as part of the IASC determination in 2000 (and a later ACCC determination) indicated that Qantas and SAA‘s direct services accounted for between 67.3% and 79.4% of the market between 1997 and 2012 (Figure 2). In the late 1990s, the most established stopover carriers were Singapore Airlines and Malaysian Airlines. Malaysian later exited South Africa, while Emirates Airline and other Middle Eastern stopover carriers have grown in prominence in both the Australian and South African markets. By 2012, Singapore had maintained 9.1% of the market, with Malaysian declining to 3.9%, and Emirates growing to a prominent 6.2%. Contemporary data is from these sources do not appear to be available. One may speculate that Emirates and other Middle Eastern stopover carriers have since grown their market share as their access to both the Australian and South African markets has increased.

Unfortunately, market share data since 2012 is not available. Instead, we can rely on BITRE data covering direct services. These data also have the advantage of being available on a monthly basis, as well as by origin and destination, and also allowing analysis by frequency and gauge. Capacity on direct services has increased consistently since the early 1990s (Figure 3). After increasing from an average of 9,249 seats per month in 1992 to 27,695 in 2003, capacity growth stalled. Notably capacity growth resumed in 2009 (average of 32,471 seats per month). Virgin’s short-lived entry gave the market a temporary capacity boost. Sustained capacity continued to grow and peaked in 2014 (average of 38,131 seats per month), declining slowly through the end of 2019 (average of 33,844 per month).

The status quo remained remarkably unchanged until the COVID-19 pandemic. Qantas continued to operate SYD–JNB and SAA JNB–PER. Both managed capacity on routes with both adjusting frequencies on a seasonal basis. This was particularly noticeable from 2014 onwards. SAA also managed capacity through frequent adjustment of aircraft size, flying variations of the A340-200, A340-300, and A340-600 on a day-to-day basis from the early 2000s (with 250, 253, and 317 seats, respectively). After the withdrawal of the A340-200 in 2011, the A330-200 (222 seats) was occasionally spotted in PER. Qantas’s aircraft choice was more consistent, flying the B747-400/400ER. Over time, capacity growth came from increasing frequencies, with the gauge remaining result unchanged for long periods. Figure 4 shows the number of flights per month increasing significantly through to the early 2010s with a very small decline in gauge.

The COVID-19 pandemic

Flights between Australia and South Africa ended abruptly in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Qantas returned to South Africa in January 2022, however SAA have yet to return, with the scale of their operation severely curtailed after entering “business rescue” (South Africa’s version of bankruptcy protection) just before the start the pandemic. It is uncertain when or even if SA will return. At present they operate only two widebody aircraft on regional routes and are scheduled to return to their first intercontinental route to Brazil in November 2023.

Qantas had planned to retire the B747-400 in 2020, but this was brought forward during the pandemic. Since returning to South Africa, they have flown SYD–JNB with the B787-9, resulting in a significant decline in gauge (236 seats on the B787, compared to 365 on the B747). In addition to the decline in gauge, the B787 also has operational and performance challenges on the eastbound sector. While Qantas now operate the B787 under more generous EDTO 330 restrictions (compared to the ETOPS 180 that Virgin operated the B777-300ER with), route diversions are relatively minor compared to ETOPS 180. Payload restrictions may be a constraint, but it is likely offset by lower operating costs. However, the loss of capacity is significant, with 903 fewer seats per week in each direction (Figure 5).

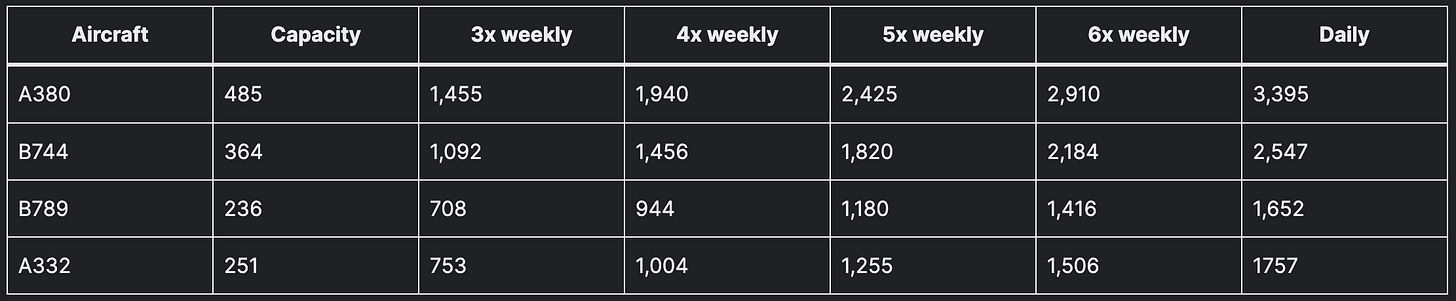

The net result has been a significantly loss in capacity since the COVID-19 pandemic. Qantas could conceptually make up the capacity shortfall at times of year when the B747 may have been operating less than daily, with higher frequency B787 operations, but there are limits. For example, daily B787 service provides more capacity (1,652 seats per week) than 4x weekly B747 service (1,456 sears per week), but B787 cannot cover the capacity once a 5x weekly B747 operated (see Table 2). Examining the timetables in the year before the pandemic, Qantas operated a minimum of 5x weekly B747, up to daily services.

The capacity loss due to the change of gauge also needs to be considered alongside the loss of capacity due to SA’s delayed return (possibly indefinitely). In response, Qantas make a strategic move to cover some of the capacity loss by introducing a new seasonal PER–JNB flight for the summer season (30 October 2022 to 25 March 2023). The 3x weekly A330-200 service covered some of the lost capacity from the change in gauge on SYD–JNB, but also the capacity loss from SA’s exit. This provided an additional 753 seats per week in each direction. When combined with the daily daily SYD–JNB service, capacity amounted to amounted to 2,405 seats per week in each direction, yet this is still marginally short of the capacity provided by a daily B747 service.

Qantas had originally planned to enter the PER–JNB market in direct competition with SAA in 2018, however the planned flight never materialised after a dispute with PER airport on terminal allocations. Qantas wanted the flight to operate from Terminals 3 and 4 to provide within-terminal connections to/from Qantas’s domestic network, with PER airport wishing Qantas to operate the flight from Terminal 1, PER‘s dedicated international terminal. While this may appear trivial, Terminal 1 is located on the eastern side of the airfield, while Terminals 3 and 4 are located on the western side, several kilometres apart. Qantas‘s other intercontinental flights in PER also operate to/from Terminals 3 and 4 (e.g., London, Rome, and Singapore).

Qantas operated the seasonal PER–JNB flight in the summer of 2022/23, intending to operate from Terminal 3 and 4, however the flight eventually operated with the inbound into Terminal 1 due to what was described as challenges related to a lack of international passenger processing facilities in Terminal 1 (alongside flights from Indonesia). Qantas does not intend to bring back the seasonal JNB–PER flights for the foreseeable future as long as it continues to encounter these operational challenges.

Enter the A380

Routes between Australia and South Africa are operating at significantly lower capacity compared to the pre-pandemic baseline. This is due to a combination of factors: SAA‘s indefinite absence from the market, Qantas‘s reduction in gauge, and Qantas‘s inability to maintain the capacity loss through sustained operation of PER–JNB.

Qantas initially attempted to fill a small part of the capacity loss with seasonal PER–JNB flights, however this has not been sustained. Looking forward, Qantas has shifted strategy upgauging the JNB–SYD flights from July 2024. At first look, switching from the B787 to the A380 appears to be a rather large increase in gauge. A daily A380 flight would carry 3,395 passengers per week in each direction compared to only 1,652 on the B787. However, there are several more considerations to look at before drawing a conclusion, including the appropriate baseline and analysis of Qantas‘s capacity management through frequency adjustments.

While the introduction of the A380 will boost capacity compared to the B787, it only approximately matches the capacity provided by the mixed SYD/PER operation between November 2022 and March 2023 (Figure 6). However, compared to the pre-pandemic baseline, the increase in capacity is somewhat smaller. While Qantas will provide more seats in July 2024 compared to July 2019, it is scheduled to provide fewer seats in August and September 2024 compared to the same months in 2019. This does not even take into account the lost capacity from SAA.

The net loss in capacity is achieved through a combination of the aircraft changes (recalling that the pre-pandemic flights were operated by the B747 and not the B787) and frequency adjustments. The A380 will be introduced from 7 July 2024, initially operating 6x weekly flights (2,910 seats per week), but the frequency is scheduled to be reduced to 4x weekly flights (1,940 seats per week) from the beginning of August 2024 until the end of the current scheduling window. Ironically, the increase in gauge at the expense of the decline in frequency and results in a net decline in capacity compared to Qantas‘s own pre-pandemic capacity (Figure 7). And even in July 2024, when Qantas‘s capacity will be greater than the July 2019, it is still a net decline from the combined Qantas and SAA capacity in July 2019. On balance, this is somewhat disappointing.

There are also additional externalities that need to be considered. Firstly, while Qantas have historically managed capacity with seasonal frequency adjustments (e.g., reducing daily to 6x weekly, and sometimes even 5x weekly for very short periods), the reduction in frequency to 4x weekly over a longer period of time is far more significant. Excluding the COVID-19 pandemic, one has to go all the way back to 2004 since the last time Qantas operated this low a frequency on the route. Even then, this was complemented by its access to codeshare capacity on SAA on the alternating days. Lower frequency operations may generate unwanted network effects (e.g., limitations of connections to lower frequency destinations), but more importantly it reduces the competitiveness of Qantas’s product, particularly to higher yielding business travellers. However, these may be partially mitigated by the shortage of direct competition with SA‘s continued absence and reduced competition from stopover carriers. While Singapore Airlines and Qatar Airways have returned most of their pre-pandemic capacity to both Australia and South Africa, Cathay Pacific and Emirates have not returned and it remains to be seen if and when this will return (this will be discussed on an upcoming analysis).

Qantas may argue that the premium heavy configuration of the A380, including the first class product, provides an offsetting competitive advantage. Furthermore, the change also allows the reallocation of the B787 to other routes where increased frequency may be more important at present (the is always a trade-off). Furthermore, the A380 also provides some performance and operational advantages over the B787, particularly on the eastbound sector, minimising or even eliminating any payload restrictions. As capacity from other carriers continues to return (SAA or stopover carriers), Qantas may be forced to reconsider, however the uncertainty in both of this timeline gives Qantas the time and space to experiment and find the optimal balance between frequency, gauge, and even other route configurations.

Conclusions

There has been a substantial loss of capacity between Australia and South Africa since the COVID-19 pandemic due to the continued absence of SAA and a reduction in gauge by Qantas due to the retirement of the B747-400.

Qantas attempted to fill some of this capacity on a seasonal basis with the introduction of flights between PER and JNB, however operational constraints have undermined the viability of the route which will not return for the foreseeable future.

Qantas have announced the introduction of the A380 to SYD–JNB from July 2024, replacing the B787-9 that has been operating since the resumption of services in 2022.

The A380 provides a significant increase in gauge but this will be offset by a reduction in frequency; the net result is an increase in capacity in the short term, but a decline in capacity in most months when compared to Qantas’s pre-pandemic capacity.

While the upgauging of flights from the B787 to the A380 has been met with some surprise, it is not a dramatic increase in capacity. When combined with Qantas’s careful and conservative capacity management trading off an increase in gauge with a reduction in frequency, capacity is relatively unchanged. As highlighted, this is somewhat concerning given the broader capacity loss in the market and competitive risks generated by the reduction in frequency. This analysis is limited by scheduling constraints with published schedules only available a year ahead. A follow-up analysis will consider Qantas’s future strategy in more detail, analysing options that its future fleet may provide, including the potential of PER, and future flights to/from MEL and CPT.