Why airlines aren't supermarkets & why investing in a new airline in Australia is stupid

And what would change our mind!

Qantas is due to publish their half year results at the end of February. If their margins and profits increase get ready for a cacophony of criticism regarding price gouging and profiteering. If margins and profits decline get ready for a similar cacophony of criticism calling management incompetent. Both are bad takes!

Meanwhile, as is typical in the #avgeek commentariat, our mate Caleb (name changed to protect their identity) reckons he can run Qantas better than the current management. Armchair CEO Caleb has a clear strategy: hire more staff, insourcing all the staff the airline has previously outsourced, buying the latest kit from Airbus and Boeing, including just paying what is needed to get ahead in the queue, installing the best hard product, wifi and entertainment, obviously much better food and drink, an improved customer-centric frequent flyer programme including lots of cheap redemptions (particularly business class upgrades), and obviously reduce ticket prices.

Caleb is confident that this will be it hit! It will generate a similar level of profit and everyone will be happy, particularly staff. Customers will love Qantas again, just like they did in their nostalgic past. He reminds us that Ansett was like this. Everyone loved Ansett, the traveling public, staff and even the media!

Caleb is convinced that his new and improved Qantas can incur dramatically higher costs while tolerating lower revenue and still somehow come out better off. The secret sauce Caleb tells us is that he knows the customer better. Because it’ll be a nicer Qantas they’ll sell more of these cheaper tickets to make up for it. This conveniently ignores that airlines aren’t flying around with a large number of empty seats at the moment. Across the Qantas group, load factors have been increasing consistently over the last decade, varying between 82% and 84% in recent years, significantly higher than the mid-70s in the early 2000s.

Another thing that Caleb’s analysis appears to miss is that prices aren’t actually high. He wants to drop prices that have actually been declining for years. Averaged across the operation, unit revenue (revenue per available seat kilometer or RASK) and yield (revenue per passenger kilometer or RPK) have been consistently declining over the last two decades. Despite the spike in the post-COVID era, inflation adjusted RASK and yield have declined 16% and 23%, respectively. If it hadn’t been for the pandemic, inflation adjusted RASK and yield declined 22% and 43%, respectively, between 2001 and 2019. So how much more does Caleb want to drop prices?!

As an aside, in order for prices to decline, costs have had to also decline. Between 2001 and 2024, unit cost (costs per available seat kilometer or CASK) has declined 26% in inflation adjusted terms. This is despite fuel cost per available seat kilometer rising 41%, meaning that unit cost excluding fuel has declined a phenomenal 37% in inflation adjusted terms during the same period! This might appear a didactic point, but if you want to sell tickets for cheaper, you need to reduce costs commensurately. But we’ll come back to this later.

Is profit enough?

Something the commentariat doesn’t always consider is that making a profit isn’t enough to build a sustainable the airline. When a new A350-1000 costs upwards of US$ 300 million, Qantas is going to need to make a lot more than a nominal amount of profit each year to justify spending that. No investor is going to give Qantas that US$ 300 million (either in equity investment or as a loan) if they’re only going to make $1.

So just how much profit must Qantas generate each year to justify that shiny new A350-1000? If an investor took that US$ 300 million and purchased a 20 year government bond they’d earn 5% annually through maturity for very little risk. Thus Qantas need to make their investors US$15 million of A$24 million each year just to match the risk free alternative.

But airlines are risky enterprises, they’re going to have to earn a lot more than just A$24 million each year. It’ll need to generate a risk premium to encourage those investors not buy the government bond and invest in them instead. And that’s just one aircraft! Scaling-up across the whole airline and the number get big really quickly!

With A$ 15.2 billion invested in fixed assets (mostly aircraft) at present, Qantas need to earn A$ 760 million annually just to match the risk free rate. So just how does an airline generate such a return? Let’s delve into the capital model of airlines a little more. Let’s first start with margins and understand how capital intensive they are and why they need to generate much higher margins than many other businesses …

Coles and Woollies do just fine with less than 5% profit margin, so why does Qantas need a 10% margin?

Let’s take a quick look at supermarkets. Like Qantas, they’ve received a lot of attention in the popular media in recent years and a fair bit from pollies too. They’ve probably experienced just as big a pile-on as Qantas.

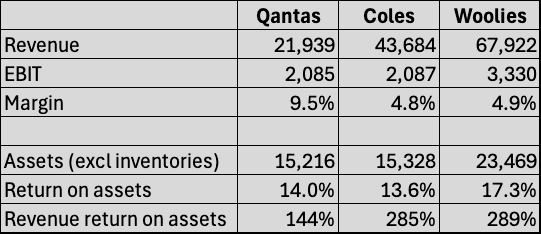

In their last financial year, Coles and Woolies made $2.1 and $3.3 billion in profit as measured by EBIT (earnings before interest and tax; we wanted to strip the decision between shareholder and debt financing for the moment, hence using EBIT). Coles and Woolies needed to generate $43.6 and $67.9 billion in revenue (i.e. sales) to make that profit, meaning EBIT profit margins of 4.8% and 4.9%, respectively. Another way to look at this was for every $1 you spend at Coles or Woolies they made 4.8c and 4.9c in profit before paying any loan interest and income tax.

Qantas on the other hand are a very different business. They made $2.1 billion EBIT but did so on only $21.9 billion in revenue, generating an EBIT profit margin of 9.5%. For every $1 you spend with Qantas they made 9.5c in profit! But why do Qantas have double the profit margin of Coles and Woolies?

The naive answer would be saying “something, something, price gouging, something, something”. Ultimately it’s because they have to! Qantas aren’t more profitable than Coles and Woolies, but how can we justify that statement?

A key difference between Qantas and the supermarkets is the amount they must invest in fixed assets to earn revenue. For Qantas this is mainly aircraft and engines but also includes a range of supporting equipment including flight simulators and maintenance equipment. For Coles and Woolies this includes property, fridges and delivery trucks.

At the end of the last financial year, Qantas needed to have $15.2 billion invested in assets excluding inventories (i.e. the stock on the shelves and the spare parts in the warehouse). For every $1 invested in assets, Qantas earned $1.44 in revenue. Comparatively, Coles and Woolies earned $2.85 and $2.89 in revenue for every $1 invested in assets. This goes a long way to show how asset intensive airlines are compared to supermarkets.

But revenue isn’t enough as it doesn’t compensate investors, profit does. When looking at profit relative to those asset a common turn of phrase is return on assets (i.e. the rate of profit earned on those assets). Intriguingly, all three firms have more similar return on assets. Qantas and Coles earned 14.0% and 13.6% on assets, while Woolies was a littler higher at 17.3%. Abstractly, we can view this as shareholders demanding a somewhat consistent return on their investments.

But in order for Qantas to generate the profit needed to establish such a return on assets they must earn higher profit margins, capeesh? Let’s look at this another way: if Qantas delivered a profit margin of only 4.9% (same as Woolies), it’s revenue of $21.9 billion would only return EBIT of $1.1 billion (instead of $2.1 billion). On an asset base of $15.2 billion this would then return only 7.0% instead of 14.0%. With only a 7% return on assets why would investors give money to Qantas when Coles and Woolies can earn double that?!

In essence, the more capital intensive a business is, the higher the margins need to be to justify the relatively larger investment in assets required to produce each $1 of revenue. This is the the ultimate challenge for an airline!

You might wonder why we’ve only mentioned Qantas; what about Virgin?

Airlines have several ways that aircraft can be financed. A binary construct makes it a choice between buying and leasing. Historically, these were treated very differently on an airline’s income statement and balance sheet.

Buying the aircraft resulted in the aircraft being listed as an asset on the balance sheet with any debt accrued to finance it listed as a liability. The aircraft depreciated in value over time and incurred a depreciation cost on the income statement that simultaneously reduced the carrying value of the asset on the balance sheet.

Leasing aircraft didn’t affect the balance sheet (with the exception of any deposits held by the lessor or maintenance reserves) and the cost of the lease incurred a cost on the income statement. Aircraft leasing is just an alternative financing mechanism and led to this sometimes being called off-balance sheet financing as the asset and debt was held on someone else’s balance sheet (i.e. the lessor).

The challenge with this is that the balance sheet didn’t show the liability for future lease commitments. Aircraft leases are typically quite long and generate long term commitments for an airline. For example, if a new aircraft is leased over a 10 year period there was no explicit accounting on the balance sheet for the liability of future lease costs even though the company was contractually committed to it. Instead, each year the rental costs were simply written up on the income statement.

In 2019, a significant change was implemented in global accounting standards which recognised this nuance by treating leased aircraft as an asset with future lease payments as a liability on the balance sheet (International Financial Reporting Standards 16, implemented in Australia as Australian Accounting Standards Board 16.). This is prudent as the airline is committed to the future lease payments just as they would be for a loan. This means that instead of leases being written up as a cost on the income statement, they incur a depreciation cost as a “right of use asset” that reduces the book value on the asset side while the rental payments also reduce the future lease payments on the liability side.

Before IFRS/AASB 16 was implemented it was difficult to measure assets used to generate revenue as the choice between on- and off-balance sheet financing (i.e. owning versus leasing). If an airline leased all its aircraft then the value of assets on the balance sheet would be very low compared to the same airline if all aircraft were owned. An example of this is Virgin: since they’re no longer ASX listed their financials aren’t reporting in line with IFRS/AASB 16 meaning we can’t analyse them alongside Qantas. FWIW, in their last financial year they reported an EBIT margin of 12.1%, somewhat higher than Qantas’s!

As an aside, IFRS/AASB 16 doesn’t apply to short term leases (less than one year) which are still treated as an expense.

If you’re not yet convinced …

So where are we going with this. Firstly, it’s clear airlines and supermarket need to operate at very different margins to earn a similar return on assets. Since airlines need to invest a lot more in assets to earn each dollar of revenue, higher margins are required to generate the profit needed to ensure shareholders earn the necessary return to make the investment in new aircraft. Airlines are very capital intensive!

We’ll be a little provocative and argue that this is why airlines need to be in more concentrated markets with fewer firms. If we had less concentrated markets and more competition the increased price competition would result in declining margins. This would lead to lower or insufficient return on assets and a shortage of capital available for investment in aircraft.

It seems somewhat abstract but we can take a somewhat extreme lesson from typical undergraduate economics courses where extreme examples are taught, not because your professor thinks they are true, but rather to frame the boundaries. Once we become familiar with the mechanisms assumptions can be relaxed to develop more realistic models.

When teaching market structures we develop two stylistic models: perfect competition where firms enter and exit the market freely and equilibrium is achieved where price equals the marginal cost and the consumer surplus is maximised. The second is a monopoly, where a single firm sets prices above marginal cost thereby reducing the consumer surplus. We relax these assumptions to develop models of duopoly, oligopoly and price discrimination. You probably/hopefully remember some of these!

You also might remember the obtuse example of the natural monopoly! Natural monopolies occur in sectors were very high infrastructure costs create a natural barrier to entry for the second supplier to the market. For example, high speed rail! The costs of laying tracks, signalling equipment, buying rolling stock is argued to be so high that this creates a natural barrier to entry for a competitor to enter the market (whether public or private).

Defining natural monopolies are easier said than done and can even be controversial, especially when technological change occurs. Historically, public utilities like water, electricity, telecommunications and post were often considered natural monopolies. Classical economists advocates that natural monopolies should be regulated as public goods.

To be clear: airlines aren’t natural monopolies and definitely not public goods, however they bare similarities of high infrastructure costs. These generate natural barriers to entry and (partly) explains why there aren’t countless investors lining up to pump billions into new start-ups to take on the incumbents! Contrary to armchair CEO Caleb’s claim, it’s not as easy as he thinks!

The correct arguments have been made that Bonza and Rex were undercapitalised. Indeed, major institutional investors weren’t lining up to pump money into them, but that’s not all of it. If it’s as easy as Cabeb thinks and if Qantas and Virgin are really milking us, then why aren’t countless other foreign airlines who have the expertise and access to capital lining up? Qatar are choosing to invest their money in Virgin, an existing operator. Singapore and Air New Zealand and a few others already tried their hand at Virgin. Why is nobody brave enough to just restart Ansett 3.0?

Come on mythical investor, we’re counting on you

For an airline to be successful you need to achieve sufficient economies of scale. You need to be large enough to share the fixed costs over a large enough number of aircraft but also generate sufficient redundancy so that single or narrow events won’t take you down. We saw Tiger suffer from a lack of redundancy early on that was nearly impossible to recover from.

Furthermore, scale develops operational redundancy. When you have an aircraft going down for a few days due to a maintenance issue this’ll have a greater effect when you’re Rex with 10 narrowbody aircraft compared to Qantas (75 excluding Qantas Link), Jetstar (77) and Virgin (96). We’ve even see Qantas struggle with redundancy issues on their widebody fleet in recent years, reinforcing the challenge for an even smaller player.

Let’s say just one quarter of the size of Qantas will be sufficient. That would require approximately $3.8 billion in assets? Now you’d need to generate 14% of that a year in profits to match Qantas, so that would be EBIT of $532 million annually. If you could achieve Qantas’s margin of 9.5% that would mean needing to generate about $5.6 billion in revenue annually.

That’s a very tall order but the problem is that is that adding a third significant player is going to reduce margins. But while margins decline, it doesn’t mean that shareholders are going to reduce the return on assets they require! Investors aren’t coming in wanting to earn less!

So instead, let’s assume that margins degrade to 6%. They still need to earn EBIT of $532 million annually to generate a 14% return on the $3.8 billion in assets. But now they’ll have to generate $8.9 billion in revenue, but still doing it on the same amount of assets? The math is no longer making sense …

But some have succeeded?

We’re sounding quite cynical and we confess, we’re playing a bit of devil’s advocate. New entrants have succeeded, but how? They tend to succeed under one or more of three conditions:

They bring some dramatic and permanent innovation that generates a sustained cost or revenue earning advantage over incumbents.

At least one incumbent is so grossly inefficient that a new entrant can generate an efficiency advantage for a sustained period that ultimately forces an incumbent into submission.

Macroeconomic shocks including exogenous geo-political events create openings.

The low cost airline revolution in Europe in the 1990s is an important case study. Led by Ryanair and EasyJet they threw away the rule book dramatically undercutting incumbent prices to win customers away from legacy carriers and even from other modes of transport. In order to undercut prices they needed dramatic changes to the business model to reduce their cost structure dramatically.

They did away with free baggage and on board services like food and drink. In fact they turned these into revenue generating opportunities. They increased cabin density to reduce per unit costs. They flew to secondary airports that were cheaper than incumbent airports. They threw away network effects and eliminated online connections, helping increase aircraft utilisation.

These are just some of the many innovations that these airlines brought (you can add your favourite one to the list). Over time, legacy carriers have borrowed some of these to reduce their own cost structures to remain competitive. Reading the list above you might think that any number of these could be implemented in Australia.

However, this misses key exogenous events that sparked some of the innovation, particularly labor mobility within the EU meant that LCCs could hire staff from lower cost jurisdictions. Start-up carriers could exploit this and undercut incumbent carriers bound by long term wage agreements.

Secondly, the European Common Aviation Area turned the EU into a single market, allowing any airline from any EU country to operates routes between two 3rd countries (e.g. Ryanair could operate flights between Italy and Greece). This meant LCCs could build scale across multiple countries.

LCCs are actually more complicated than they appear

We’ve argue before that LCCs are misunderstood as they are rarely the same thing. It refers to a principle which is that if you want to sell cheaper tickets you need to reduce your cost base.

A challenge is that some mechanisms to reduce costs ultimately reduce revenue generating potential. For example, higher utilisation means flying at times that are less convenient which in turn may degrade revenue, or operating to a secondary airport may in turn cost less but also degrade revenue.

At the same time, the aircraft are much the same and all else being held constant, LCCs still need to earn the same return on assets but on lower revenue meaning they may even need to earn higher margins! This means cost reductions must exceed price reductions! It was all good and well for Bonza to fly (full) B737s (we have our doubts about full, but let’s go with it) but they had to still generate the same or higher return on assets that Qantas and Virgin needed, yet doing it earning less revenue.

The only way is a higher margin. So what were their great innovations to operate more efficiently than the incumbents so that their cost reductions would exceed price reductions? All while doing this with fewer economies of scale? We await the revelation!

Earlier on we briefly touched on Qantas’s cost structure, highlighting how their unit cost has declined 26% in inflation adjusted terms between 2001 and 2024 (37% when stripping out fuel). This has allowed them to increase profitability and return on assets while seeing unit revenue and yields decline 16% and 23%, respectively. What this really highlights is Qantas’s efficiency, and their increasing efficiency over time! Qantas are actually very efficient!

But Virgin Blue did it?

An important counterpoint is Virgin Blue. While younger readers likely see Virgin as a permanent fixture alongside Qantas, they’re still relatively young having been established in August 2000. But Virgin was founded while Ansett was smouldering and waiting for the inevitable. Virgin bet that Ansett wouldn’t be able to find (a close to impossible) agreement between shareholders, labor, banks and government to continue, and that they would go under. Virgin’s timing was impeccable and Ansett’s demise was hastened by the 9/11, but in hindsight their demise was inevitable.

Outside of exogenous events, the pathways lead back to the same point: the new entrant needs to generate some efficiency advantage, whether that be through innovation or incumbents running a terribly inefficient ship! Which leaves us as at the question: is there something that Qantas and Virgin are missing in terms of efficiency, something that a well-capitalised start-up can bring to market? Particularly something that Qantas and Virgin aren’t capable of doing?

And no, this isn’t “something, something, AI, something, something, decentralised, blockchain”. Let’s be real and pragmatic! While we’ve ridiculed wannabe start-up Koala Airlines for vague promises of such they’re (inadvertently) onto something. That something probably isn’t AI, but it recognises that success requires innovation.

The argument can certainly be made that pre-COVID Virgin were inefficient with a weak balance sheet and large debt dragging their results down and leaving them vulnerable. Rex made a bet that Virgin would go the same way as Ansett in the face of an exogenous macroeconomic shock. However, their bet failed and Virgin didn’t succumb. Instead, Virgin were restructured and recapitalised under new ownership (Bain Capital). While Virgin were weak and vulnerable, Rex lacked the capital and scale to fill the gap, and fill it quickly enough.

So what would change our mind?

Any new entrant is going to face the same labor market conditions and supply side constraints as the incumbents. They’re likely to face similar or more challenging capital constraints. They’re going to be less efficient and operate at an efficiency disadvantage for some time, undermined by a lack of scale and redundancy.

This will require investors with a high risk appetite and a very long term view whose capital constraints may differ. It seems from this vantage point that the only possibility would be a benevolent investor, one that isn’t as interested in return on assets. In return for what? Ego? Strategic or geo-political interests? Sounds more like a Tom Clancy novel than reality.

Something that we haven’t mentioned are the slot constraints that a new entrant will face. This receives a lot of attention in the public discourse, albeit somewhat distorted. A huge advantage that incumbents hold is that the lack of available slots at Sydney and to a lesser extend Melbourne, particularly at peak time. An argument that we’ve made before is that redistributing slots from incumbents to new entrants isn’t likely to bring about a significant public benefit. New entrants that take slots will be less efficient than incumbents. Just as we saw with Rex, without any cost advantage they simply couldn’t maintain lower ticket prices. Furthermore, this will make incumbents less efficient at the same time as they’ll lose some of their economies of scale!

However, what will interest us is an exogenous shock that significantly increases the number of slots available at major airports. Rather than move the deckchairs around on the Titanic, let’s consider making more deckchairs available! The increase in slots would need to be significant enough to generate enough space for a new entrant to establish sufficient scale that would encourage investment. Ring-fencing these new slots for new entrants for a fixed period would achieve this.

So how do you create more slots? Well, the answer is simple: built more runways and the associated terminal space. Sounds easy, right? Well, it takes political will, and there isn’t much of that going around!