Why regional jets are misunderstood and why they wouldn't have worked for Bonza

A very common comment that you’ll come across when engaging in the popular aviation discourse is that route X to Y will be a good size for **insert type of regional jet**. The context will be in relation to a thinner regional route, for example when Bonza went bankrupt in April 2024, many comments were that many/most of their routes would have been better suited to smaller aircraft like a 100 seat E190 as opposed to the 186 seat B737-8 aircraft they were flying.

The comment isn’t misplaced as many/most of Bonza’s routes didn’t have sufficient demand to fill 186 seats at a price that was able to cover their costs and earn a sufficient profit to generate the required return on assets. This is important as Bonza’s administrators specifically pointed to their pricing as one of the reasons for their failure. The administrators calculated Bonza's average fare at A$ 104, 26% lower than market average of A$ 141.

Essentially, in order to fill aircraft sufficiently, Bonza were having to price tickets too low to cover their costs. The challenge is that had Bonza raised their prices they likely would have seen lower passenger numbers. Higher prices would have resulted in some customers switching to alternatives like other airlines, connecting options or even driving. Furthermore, lower prices were stimulating demand, and thus higher prices would have failed to stimulate demand.

So smaller aircraft would have been more sustainable, however there is a key problem as the smaller the aircraft, the higher the unit cost. Therein lies one of the most misunderstood dynamics in the business: the cost dynamics of regional jets. Let’s explore …

Some context about cost structure

There are two important definitions that we need to understand for this analysis:

Trip cost: the total cost of making a given trip.

Unit cost: the total cost of making a given trip divided by the number of passengers the aircraft carries, often presented as the cost per available seat kilometer (CASK) or mile (CASM).

As a generalisation, smaller regional jets like an E190 will have a lower trip cost than a narrowbody jet like a B737 or A320 for a given trip as it’ll burn less fuel, incur lower enroute navigation charges, lower airport fees, lower staff costs (fewer cabin crew), etc.

However, smaller regional jets will have a higher unit cost than narrowbody jet on that same route, as the larger narrowbody jet will be able to share the fixed costs over a larger number of passengers and because variable costs increase at a decreasing rate (declining marginal costs).

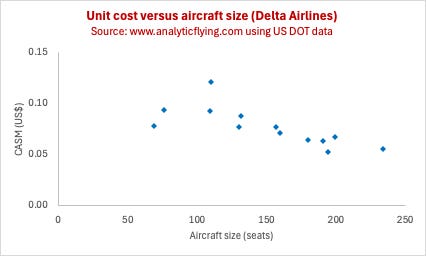

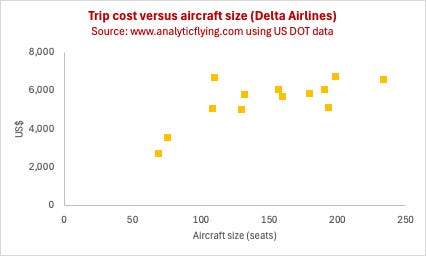

Conceptually, this makes sense, but is there empirical data to support this? Data from the United States allows us to show this in action. We use a single airline (Delta Airlines) to show the relationship between unit cost and aircraft size, and trip cost and aircraft size across their regional and narrowbody fleet fleet. Using a single airline is import since we can assume a consistent underlying cost structure.

Using this example, the first figure (below) shows us how the unit cost of Delta’s fleet declined as as the aircraft size increases. There is one outlier at the 110 seat size, however the data shows a clear picture. For example, the B737-800s has a unit costs of 7.1 cents per available seat mile, 24% lower than the 9.3 cents per available seat mile of the CRJ 900.

However, the second figure shows how trip cost increases with aircraft size, with the CRJ 900 - despite the higher unit cost - has a significantly lower trip cost than the B737-800. The CRJ 900 will cost US$ 2686 to cover a 500 mile trip, 53% less than the US$ 5671 on the B737-800.

So the empirical evidence supports the conceptual argument that larger narrobodies are more efficient than their smaller regional jet contemporaries. But there’s a big but, as this only benefits the airline if they are able to fill the extra space, and fill it at a higher enough price. However, flying around larger aircraft generates more risk due to the higher trip cost.

Meanwhile, a regional jet presents lower risk than a narrobody jet since its trip cost is much lower in the event of an empty flight. However, its higher unit cost means that it’s required to earn a higher unit revenue (revenue per available seat kilometer or RASK), all else being held constant. This presents a conundrum for airlines.

So why do airlines then operate regional jets?

The contemporary history of regional jets takes us back to the US where major legacy airlines like American, Delta and United have an extensive fleet of regional jets flying with feeder airlines. These typically operate under linked but seperate brands (e.g. American Eagle, Delta Connection and United Express). The feeder airlines are wholly owned subsidiaries (e.g. Delta’s subsidiary Endeavor Air) or contracted out to independent firms (e.g. Delta also utilise capacity operated by Republic Airways and SkyWest Airlines).

All US legacy carriers are strongly dependent on the hub-and-spoke model due to the fragmentation of the US population with most hubs operating as hybrids between banked and rolling hubs to differing extents. Irrespective of the banking strategy, hub-and-spoke models favour higher frequency operations, lending itself to more flights on smaller aircraft rather than fewer flights on larger aircraft, all else being held constant.

For example, if an airline has two aircraft types, a 50 seat regional jet and a 150 seat narrowbody, a route with an expected daily demand for 150 seats can be operated 3x daily on the 50 seat regional jet or 1x daily on the 150 seat narrowbody. The higher frequency operation will enable more connections and offer more flexibility for customers, thereby increasing yields and unit revenue. However, the million dollar question is whether the increase in yields will be sufficient to increase unit revenue more than the increase in unit cost imposed by regional jets?!

The second consideration is that crew at regional carriers are paid less than their counterparts at mainline carriers. This led to the development of “scope clauses” in labor bargaining agreements that limit the capacity that mainline carriers can employ with regional jets. For example, Delta’s agreements with crew unions limits them to operate a maximum of 125 aircraft with 50 or fewer seats, 102 aircraft with 51-70 seats, and 233 aircraft with 71-76 seats (there are other constraints that limit stage lengths and hub versus non-hub flying).

Another interesting artefact of US regional jets is how some operate with relatively low density premium layouts. This is ostensibly to maintain aircraft within scope clause limits. For example, Delta’s CRJ 900s are fitted with 76 seats (12 first/business and 64 economy) whereas many other legacy carriers like Lufthansa and SAS operate the same aircraft with 90 seats. Other examples include the Delta’s E175 with 76 seats (12 first/business and 64 economy) compared to 88 and 82 on KLM and LOT, respectively.

The same is found at other cutoffs, sometimes with rather peculiar configurations. For example, United wanted to replace some 50 seater regional jets, but the with the CRJ 200 out of production, they took new CRJ 700s with a reduced MTOW and fitted it with 50 seats (10 first/business and 40 economy), calling it the CRJ 550. Comparatively, United’s original CRJ 700s seat 70 passengers (6 first/business and 64 economy). All this to remain within the scope of the scope clauses!

It works for US legacies, so why isn’t this a generalisable solution?

Regional jets are a generalisable solution, as evidenced by them operating in many other countries, not just the US. Scope clauses aren’t just a US phenomenon either with them being present in Canada, while other countries may have similar considerations within Enterprise Bargaining Agreements, although fixed limits on the number of aircraft and aircraft size isn’t as widespread. However, the complication remain the same: can the airline generate sufficient revenue premium to offset the higher unit cost?

A great example of this is Qantas who utilise a range of regional jets under the QantasLink brand. In some cases they use regional hets to operate a single daily flight on thinner routes (e.g. Qantas deploy the A220 on its once daily Melbourne-Coffs Habour flight), while on other routes it allows them to operate at greater frequency than they would utilising a narrowbody (e.g. Qantas deplot the A220 4x daily on Melbourne-Hobart), thus generating more connections and increasing passenger flexibility.

But it means that the higher unit costs needs to be recovered in higher ticket prices. On thiner routes, it results in higher ticket prices for all passengers while on routes where regional jets are deployed to increase frequency it can be recovered through a yield premium for some passengers on some flights through price discrimination including generating higher yields off increased network flows and passengers willing/able to pay for greater schedule flexibility.

But this isn’t generalisable to all airlines. For example, this simply doesn’t work for most LCCs as their business model relies on reducing or minimising unit costs relative to competing or incumbent carriers. This is needed to allow for lower unit revenues and thus ticket prices. In fact, as we’ve argued before, LCCs must reduce unit costs by more than the decline unit revenues to achieve the same return on the asset.

The lesson: the higher unit costs of regional jets doesn’t suit LCCs

So back to Bonza, it’s simply not the case that their routes were better suited to a regional jet, well at least not within their business model! While regional jets would better match capacity with demand, it would significantly increase unit costs and thus require them to increase ticket prices, which as we’ve already noted, were too low to cover the costs of the B737-8s.

But this isn’t really Bonza specific. Just like any LCCs, they wouldn’t be able to generating higher yields from increased network flows and passengers willing/able to pay for greater schedule flexibility, since they didn’t have this to begin with. It simply isn’t part of the business model, or any conventional LCC for that matter.

But this also goes a long way to explain why LCCs typically don’t fly regional jets. It’s often argued that LCCs typically operate one fleet type as a cost savings measure for crew and maintenance. This is true, but it’s also a function of the narrower scope of aircraft that suit the LCC business model. Regional jets typically don’t suit their business model due to higher unit costs, while larger widebody aircraft undermine other cost structure needs, including turnaround times.

Smaller niche LCCs might find the lower trip cost useful, particularly in environments with limited or not competition, or where incumbents are so inefficient that even flying regional jets would result in a lower unit cost than incumbents, but these sound more like outliers than generalisations.