Chart of the week #7: How much of an impact did open skies have on Australia-US travel? Part 2

Last week’s “chart of the week” looked at the impact of an open skies agreement between Australia and United States that entered into force in 2008. The open skies agreement led to dramatic growth in passenger traffic between Australia and the US. In the 18 years before open skies, annual passenger traffic increased from 1.0 to 1.7 million (700,000 increase). In a little over a decade since (11 years), annual passenger traffic increased from 1.7 to 3.3 million (1.6 million increase)!

The open skies agreement was a clear structural break leading to a surge in passenger flows between Australia and the US. But how did it change the game?

Last week we highlighted how the previously restrictive BASA made it difficult for new entrants to gain a foothold in the market. Combined with the dominance of incumbent carriers, new entrants were limited by an inability to grow a competitive network quickly enough. So let’s look at a breakdown of passengers numbers by airlines before and after open skies to examine this in more detail.

Before open skies

In the early 1990s, Qantas and United Airlines were already the dominant carriers between Australia and the US. United had acquired the routes via its purchase of Pan American World Airways’ Pacific division in 1985. However, they were not the only US carriers on the routes. Both Continental Airways and Northwest Airlines had a significant foothold in the market, but these is some nuance …

Air travel in the early 1990s was a little different to now. Until the introduction of the B747-400 in 1989, most routes between Australia and the US mainland required fuel stops. The B747 SP allowed non-stop flights, however its smaller capacity and significantly higher operating costs made it a niche aircraft.

Most airlines and flights took at least one stop, but sometimes two, aboard B747-200s or DC-10s. For example, Qantas and United flew B747-200s via Honolulu, Fiji, Tahiti, and/or Auckland (in addition to non-stop B747 SP flights). Continental operated two-stop flights with B747-200s and DC-10s via Honolulu, Tahiti and/or Auckland.

In the 1990s, non-stop flights became the norm as Qantas and United were early adopters of the B747-400. Meanwhile, Continental didn’t order the B747-400, lost their ability to compete with non-stop flights and subsequently excited the market in 1994. Meanwhile, Northwest Airlines entered the route in 1991, however choosing to fly to Australia via Japan, exploiting fifth freedom rights they enjoyed between Japan and Australia. That service was short-lived and they also exited the market in 1994.

Finally, there were several third country carriers enjoying fifth freedom services between Australia and the US. This included Canadian International Airlines (and their successor Air Canada), however these flights only carried fifth freedom traffic to/from Honolulu, not the US mainland. These fifth freedom flights were typical of their generation where aircraft were unable to operate non-stop long haul flights. While Continental and Northwest exited, fifth freedom services continued and even grew. Air Canada continued to operate via Hawaii all the way through to 2007 whereafter flights were shifted to non-stop services.

Additionally, Air New Zealand exploited similar opportunity, extending their own flights between New Zealand and the US onto Australia (e.g. routing SYD-AKL-NAN-HNL-LAX). Following the elimination on the limitation of “beyond rights” as part of the extension of the Australia-New Zealand Single Aviation Market in the early 2000s, Air New Zealand shifted to offering non-stop flights between Australia and the US (assisted by the the introduction of the B747-400).

After open skies

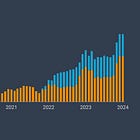

Following the implementation of open skies the market boomed. The removal of capacity and growth constraints brought about the entry and growth of new carriers including Virgin Australia (initially V Australia), Delta, Hawaiian, Jetstar, and American.

Virgin entered in 2009 and grew capacity quickly, something that wouldn’t have been possibly under open skies. By 2019, the accounted for 15% of the market! Delta also entered in 2019 and while they didn’t grow capacity they partnered with Virgin in a joint venture. By 2019, their combined capacity amounted to 21% of the market.

Hawaiian had entered the market in 2004, but their growth was limited. Between 2004 and 2008, their passenger volumes were flat, whereas by 2019 they were carrying more than four times as many passengers annually.

American entered the market in 2015, and has grown their capacity achieving a 5.5% market share by 2019. However, American’s capacity can’t be separated from Qantas who they partner with via a joint venture. This highlights the most consequential observation from the figure. What happened to Qantas in all of this?

Between 2009 and 2019, Qantas and Jetstar combined have carried 43% more passengers while their market share has decline from 59% to 51%. They have a smaller piece of the pie, but a smaller piece of a much bigger pie! When combined with the joint venture partner, they have carried 59% more passengers while their market share only decline from 59% to 56%! A superficial view is often that incumbent carriers won’t benefit from open skies, but this example highlights how incumbent carriers can exploit and even thrive under open skies!

United’s passenger numbers increased by only 14% between 2009 and 2019. Their growth was likely challenges by the greater number of new entrants on the US side of the market. However, that changed dramatically in the post-pandemic market where United has dramatically increased capacity with limited success. See our more detailed analysis of recent trends in the Australia-US market here:

One casualty from open skies has been the loss of fifth freedom carriers. While many commentators argue fifth freedom routes to be a panacea for competition their likelihood of succeeding is low. They tend to be most successful in a limited range of scenarios including where technical stops are required, where the marginal cost of operating the route is very low, or where capacity is otherwise severely limited. We have also discussed this in detail before:

The constrained BASA in the pre open skies era created an opportunity for fifth freedom carriers, however shift to open skies has increased competition that has driven out the remaining fifth freedom carriers. However, however the net increase in capacity negates their loss, and then some!