What limits fifth freedom flights to Australia?

Last week, there was an interesting exchange on social media regarding the granting of fifth freedom rights on routes to/from Australia. The discussion stemmed from the controversial decision by the Australian government to block access to additional market access for Qatar Airways which we have discussed in detail in two previous blog posts: Implications of the Australian government’s decision to block an additional frequencies for Qatar Airways and Who stands to benefit from Australia’s decision to block additional market access to Qatar Airways?.

Fifth freedoms are defined by the ICAO as the “the right or privilege, in respect of scheduled international air services, granted by one State to another State to put down and to take on, in the territory of the first State, traffic coming from or destined to a third State.”

Some prominent examples of fifth freedom flights involving Australia include Qantas and British Airways’s SYD–SIN–LHR flights where QF carry local traffic on the SIN–LHR sector (in addition to the SYD–SIN and SYD–LHR sectors), and BA carry local traffic on the SIN–SYD sector (in addition to the LHR–SIN and LHR–SYD sectors). An alternative application is where foreign airlines flying to Australia continue onto New Zealand carrying local traffic between Australia and New Zealand (or to New Zealand continuing onto Australia). Contemporary examples include EK’s DXB–SYD flights continuing to CHC, or LA’s SCL–AKL flights continuing to SYD.

It is argued that fifth freedom flights advance competition by adding capacity and increasing consumer choice. Many commentators go further to argue that expanding fifth freedom access to foreign carriers would go a long way to solve market concentration challenges in Australia. Recently the ACCC went as far as arguing that allowing foreign carriers access to the Australian domestic market would do the same. Called cabotage, this is an extension of fifth freedoms (also called eighth freedoms). This analysis questions these assumption, analysing the history and context of fifth freedom services, using the Australia-New Zealand market as a case study. The analysis shows how complex market dynamics generate operational and economic challenges for fifth freedom operations that limit their ability to compete with the incumbent home market carriers. This goes a long way to explain why fifth freedom rights are significantly underutilised and unlikely the most effective solution to increasing competition in the market.

History of fifth freedom privileges, why do they exist?

Fifth freedom rights and privileges are generally more widely available than assumed. While it may surprise many readers, most BASAs provide for some fifth freedom opportunities, although with significant limitations more often than not. Even when they are available without limitations, they are still significantly underutilised. To understand this, let’s first consider the history of fifth freedom rights and flights.

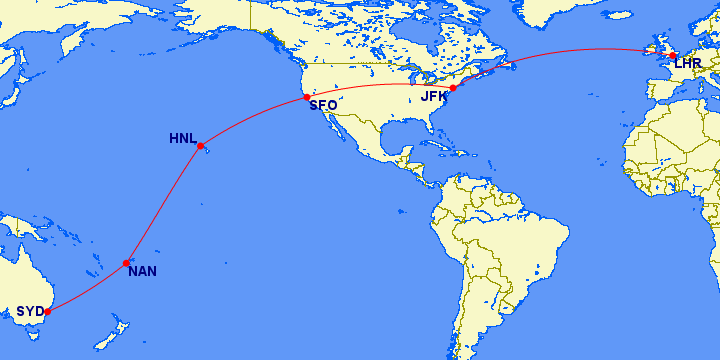

Contemporary long haul aircraft can reach Europe from eastern Australia with one-stop, or the United States non-stop. However, this is a relatively recent phenomenon. One-stop SYD–LHR flights were only achieved in 1990 with the introduction of the B747-400, while the first jet flights on the B707-100 in 1959 needed as many as 7 or 8 stops stops to complete the same flight, either via Asia or via the US. The maps in Figure 1 show this progression over time.

Figure 1: Evolution of QF‘s SYD–LON services over time

Historically, long haul flights operated at much lower frequency than present day flights. Furthermore, airline partnerships including codeshares and joint ventures were not well developed, and airline long-haul networks served a larger number of destination rather than relying on connecting short haul flights provided by partner airlines through foreign hub. Thus long-haul flights with multiple stops served a dual purposes, allowing airlines to connect passengers to a greater variety of destinations. However, serving a large number of destinations on a single flight results in unbalanced traffic through the intermediate destinations and fifth freedom rights were vital to the viability of long haul flying. They were generally granted and utilised on a reciprocal basis, limiting protectionist instincts of governments. However, continuous improvements in aircraft range over time reduced the number of stops long haul flights needed to make. This also coincided with the development of the hub-and-spoke model (spurned by airline deregulation in the US in the late 1970s) and the contemporary model of connecting networks through airline partnerships including joint ventures and codeshares.

The trend towards liberalisation

As the demand for long-haul flights grew so did the movement towards liberalisation of BASAs, including the increased popularity of open skies agreements. While older generation BASAs allowed provided for a large number of fifth freedoms, they were more likely to limit frequency and/or capacity, or explicitly state or limit intermediate or beyond points. Older generation BASAs also tended to be very specific about the routes, frequencies or capacity that even home carriers were limited to. Over time, these agreements were liberalised, removing many of these constraints, including on fifth freedoms. However, some of these BASAs are still in place, often due to the inability of countries to find consensus on a more modern architecture.

The Australia-France BASA (1965) is still in place and is a typical example from that era. The agreement specifies the fifth freedom options for both intermediate points (e.g., between Australia and France) and points beyond (e.g., flights from Australia to France, continuing onwards). The combination of these points would appear generous by today’s standards, allowing airlines to fly an Asian routing via ATH, one of CAI/THR/BGW, one of KHI/CMB, one of BKK/RGN, and/or one of SIN/KUL/CGK), and also beyond to LON. Airlines flying a Pacific routing were allowed NAN (mandatory), PPT, SFO, NYC and/or LON, with onwards service to one of FCO/ATH. Furthermore, both routings could be combined.

However, the BASA uses a (now) archaic method of limiting capacity that creates de facto on frequency. Each country is allowed to allocate 3 units of capacity (weekly) with a flight counting for parts of a unit based on aircraft size. For example, QF’s B787-9 (236 seats) would amount to 0.5 units, allowing 6x weekly services, while QF’s A380 (485 seats) would count for a full unit, allowing 3x weekly services. While these constraints would be somewhat limiting in a contemporary setting, the capacity was likely adequate for its time.

Contemporary BASAs are somewhat simpler, often specifying frequencies or total market capacity rather than units, and simplifying fifth freedom options (often by a smaller list of exclusions rather than specifying inclusions). Open skies agreements remove all of these specifications. For example, the Australia-New Zealand open skies agreement allows airlines from each country to fly any route at any frequency, with any intermediate stops or points beyond. This allows limitless fifth freedom possibilities, subject to the arrangements with third countries. So why is it that so few fifth freedom flights between Australia and New Zealand exist?

Fifth freedom flights between Australia and New Zealand

Liberalisation of air travel between Australia and New Zealand began with the Single Aviation Market in 1996, followed by an open skies agreement that entered into force in 2000 (even though the treaty instrument itself was only agreed to in 2003). The reforms removed all caps and limitations on capacity, frequencies, destinations and services beyond. This meant that any Australian or New Zealand domiciled airline could fly any routes between the two countries at any frequency or scale. It also allowed airlines from each country to operate domestic services in the other country, and a range of services beyond (subject to limitations that may exist in arrangements with the third country). Furthermore, it also increased fifth freedom privileges between Australia and New Zealand by carriers from third countries by removing of capacity limitations (again, subject to limitations that may exist in arrangements with the third country).

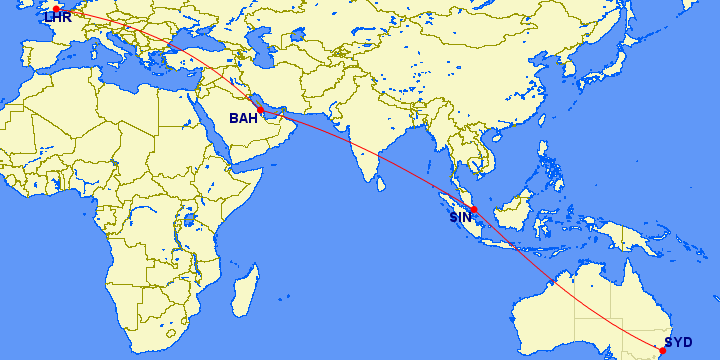

Liberalisation led to a sizeable increase in passengers numbers between Australia and New Zealand. Prior to liberalisation, the market was limited to a single designated carrier from each country (QF and NZ). The removal of capacity constraints allowed QF and NZ to increased capacity significantly, after several years of stagnant passenger numbers (Figure 2). It also opened QF and NZ to competition from AN, KC, and SJ (a subsidiary of NZ) in 1995 and 1996. AN and KC failed to gain a foothold, exiting relatively quickly, however SJ became an established player, reaching a market share of 13% by 2003. VA and JQ entered the market in 2004 and 2005, respectively. SJ lost ground after the entry of VA and JQ and it was absorbed into NZ by 2008.

Liberalisation also brought about an influx of fifth freedom capacity through a combination of new entrants and removal of capacity restrictions on incumbents. Pre-liberalisation carriers included AR, BA, BR, MH, OL, TG, UA, and WR, and they were joined by GA 1997 and LA in 1997 and 1998, respectively. After the introduction of open skies, CA (2000), CI (2000), EK (2003), BI (2003), PR (2015), SQ (2016), and D7 (2022) also joined the fray. Many of these carriers have since ceased flying fifth freedom routes, yet in all cases (except AR) they have continuing flights to/from Australia and/or New Zealand.

By 2019, the last full year before the COVID-19 pandemic, passenger numbers between Australia and New Zealand totalled 7.3 million, 209% higher than the 2.4 million passengers carried in 1995. At a group level, NZ and QF initially grew their market share post liberalisation, in both cases buoyed by the introduction of LCC brands (SJ and JQ) to complement mainline service. However, NZ lost market share when SJ exited. Subsequently, VA‘s entrance ate into both NZ and QF‘s market share.

The market share of fifth freedom carriers fell after the introduction of open skies although it recovered over time to reach a relative peak of 17% in 2016, still below pre liberalisation levels. However, fifth freedom market share fell rapidly and consistently after 2016. By 2019, it had fallen to 6%, its lowest levels on record. Notably, the home carriers have been the primary beneficiaries of market liberalisation, adding capacity quicker and more consistently, and even more sustainably, than fifth freedom carriers. Furthermore, incumbent carriers are more likely to loose market share (and dare one say, are more threatened) by new market entrance in the home markets than fifth freedom carriers, as evidenced by the entrance of VA.

It’s somewhat of a contradiction, but as access to fifth freedom opportunities increased, the relative market share has declined. It is difficult to generalise since each route or network is different, but in the case of Australia-New Zealand we argue that it is due to market and competition dynamics (while it is difficult to generalise, we would expect this to be the case in many countries/markets). Firstly, the removal of capacity constraints that opened more opportunities for fifth freedoms also applied to the incumbent home carriers who were better positioned to exploit liberalisation due to significantly stronger network effects, yield premiums, and distribution capacity in these markets.

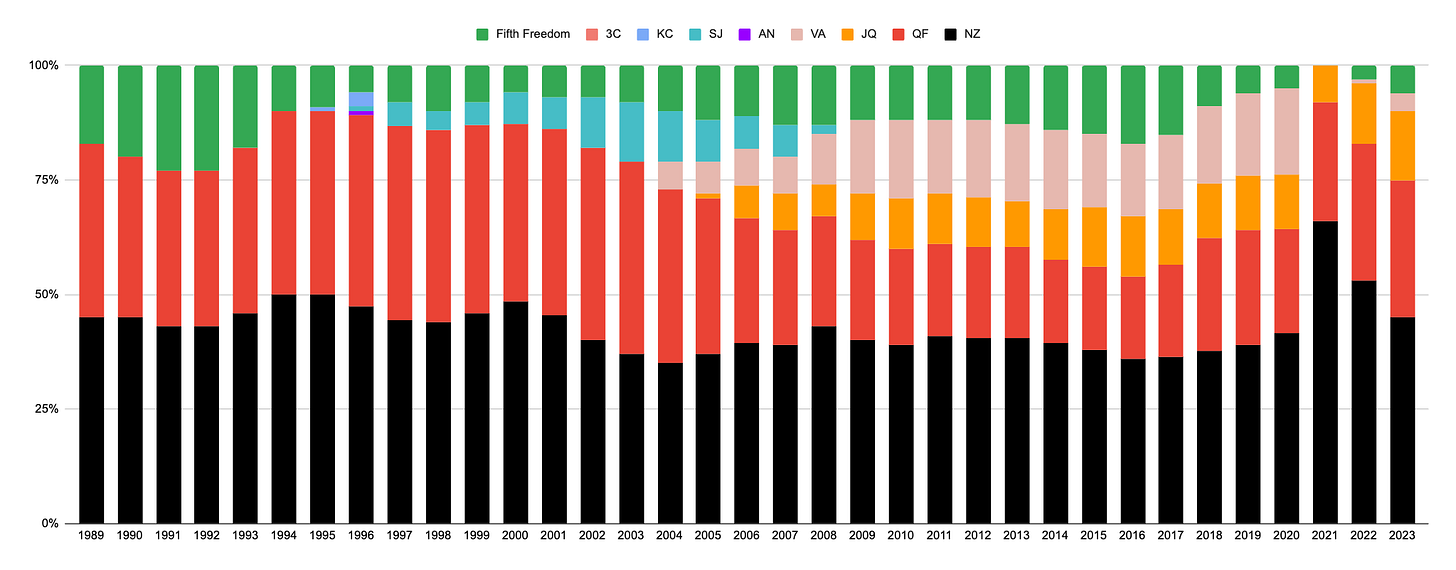

A fifth freedom carrier will operate at a significantly narrower network, a small number of routes and city pairs, at lower frequency. QF and NZ offer a large number of city fair, often at high frequency. For example QF (including JQ) connect four Australia ports (SYD, MEL, BNE, and OOL) with four New Zealand ports (AKL, CHC, WLG, and ZQN), thereby offering 16 city pairs (Figure 3). NZ fly 17 city pairs by offering 8 Australian destinations from AKL (ADL, BNE, CNS, HBA, MEL, OOL, PER and SYD), and a smaller range from CHC (BNE, MEL, OOL, and SYD), WLG (BNE, MEL, and SYD), and ZQN (MEL and SYD). NZ‘s operation is somewhat different to QF‘s with a greater centralisation from their AKL hub they are able to serve more destination in Australia, while QF‘s greater fragmentation serves fewer Australian ports but compensating for more direct city pairs.

Table 1 shows the contemporary timetable for SYD–AKL services (SYD–AKL is the highest traffic Trans Tasman route, connecting the largest hubs on each side). QF (including JQ) and NZ fly multiple frequencies, with departures from early morning through late late evening. D7 and LA are the only fifth freedom operations with one daily frequency, scheduled at a similar time. Their schedule is ultimately defined by exogenous considerations (discussed later).

Challenges operating fifth freedom routes

Incumbent home carriers have significant network effects, providing domestic and even international connections from their home ports (JQ even has a small domestic network in New Zealand that provides network effects at the destination). They also have established sales and distribution capabilities in the home markets. Airlines have significantly smaller network effect and sales and distribution capabilities in foreign markets. However, when operating to a foreign market, the disadvantages in the foreign market are balanced by the advantages in the home market. However, when operating a fifth freedom route, a foreign carrier is subject to disadvantages on both ends. An exception to this might be a LCC that is designed to operate with a lower cost structure that mitigates these competitive shortcomings, and is less dependent on the network model.

Moreover, not all carriers that may otherwise be interested in fifth freedom services have the spare capacity (aircraft and/or crew), or the scheduling flexibility. Others may have strategic partnerships – including joint ventures – with home carriers that would provide more efficient network effects. For example, UA would benefit from NZ and VA‘s higher frequency and wider number of city pairs more than it would from a single low frequency fifth freedom service (UA has a joint venture partnership with NZ, and a codeshare partnership with VA). This was particularly evident during the ACCC approval of the QF–EK joint venture which focused extensively on the effect on Trans Tasman services (given EK’s existing fifth frequency services).

While the liberalisation allowed all carriers to expand frequencies, destinations, and capacity on both sides, the benefits have accrued mostly to the incumbent home carriers rather than fifth freedom carriers. There is no doubt as to the public benefit of liberalisation, however the analysis underscores that fifth freedom capacity (and possibly cabotage) is not the most important element to increasing competition.

Why do carriers fly fifth freedom routes?

At present, a small number Trans Tasman fifth freedom routes are flown (see Table 2). The number and frequency have decline in recent years although several new fifth freedom routes have also recently been announced. There are several motivations for airlines who fly fifth freedom routes, and we categorise the Trans Tasman routes into three groups with significant overlap.

Firstly, tag-on flights where an airline wants to operate to two destinations but may have insufficient traffic to operate one or both destination independently. By combining the two destinations (operating as a tag-on flight), they may also serve one or both destinations at higher frequency than they otherwise might do independently. An example of this is LA‘s SCL–AKL–SYD flight which carries fifth freedom traffic on the AKL–SYD sector. The economic benefit to LA is that it exploits the revenue earning potential of the empty seats on the AKL–SYD sector created by the passengers flying only the SCL–AKL sector. This compensates for the competitive disadvantage of a longer SCL–SYD flight compared to a non-stop sector.

A second motivation is aircraft scheduling. Many flights to/from major international transit hubs are timed to depart from and arrive at the hub during specific windows. Banking – as it is termed – allows airlines to provide the largest number of optimally timed connections. To achieve this, airlines may schedule significantly ground time at outstations to optimise schedules. EK is a prominent proponent of this strategy: some of their flights to Australia spend nearly half a day on the ground before returning home. For example, EK 414 (DXB–SYD) and EK 408 (DXB–MEL) arrive in the late evening before returning as EK 415 (SYD–DXB) and EK 409 (MEL–DXB) early the following morning (see timings below), ostensibly connecting from/to the same banks in DXB.

EK 414 DXB–SYD 2:05am 10:25pm

EK 415 SYD–DXB 6:00am 1:10pm

EK 408 DXB–MEL 2:10am 10:30pm

EK 409 MEL–DXB 6:15am 1:05pm

An alternative series of flights, EK 412 (DXB–SYD) and EK 406 (DXB–MEL) arrive early in the morning before returning in the evening as EK 413 (SYD–DXB) and EK 407 (MEL–DXB) (timings below). The ground time lowers fleet utilisation and generates a large opportunity cost. Simply put, aircraft do not generate revenue sitting on the ground. Furthermore, airports charge significant parking fees for aircraft with long turnaround times since they also face an opportunity cost. Fifth freedom services puts the aircraft to productive use instead.

EK 412 DXB–SYD 10:25am 7:05am+1

EK 413 SYD–DXB 9:45pm 5:15am+1

EK 406 DXB–MEL 10:05am 6:30am+1

EK 407 MEL–DXB 22:15pm 5:15am+1

The combination of the late arrival (EK 414/415) and early departure (EK 408/409) does not provide a strong platform for onwards fifth freedom services to New Zealand since the scheduling would be somewhat obscure (and also run into curfew challenges in SYD), the early morning arrivals (EK 412/406) and late evening departures (EK 413/407) are more conducive to onwards fifth freedom services to New Zealand. EK exploit this by extending EK 412/413 from SYD to CHC. Additionally, it allows EK to serve an additional destination that it might not otherwise serve. Until 2018, EK 406/407 continued to AKL, but this was dropped in favour of increased services by joint venture partner QF, reinforcing the earlier argument regarding the network efficiencies of fifth freedom flights compared to partner network models.

EK 412 SYD–CHC 8:50am 1:55pm

EK 413 CHC–SYD 6:20pm 7:40pm

Another scheduling motivation are flights that are timed to fly overnight to increase the yield potential of premium passengers. This also results in significant ground time at the destination, generating similar costs. An example of this is CI‘s Australian operation flights. CI fly from TPE to SYD, MEL and BNE, with all flights arriving in Australia in the morning before an overnight return flight (schedule below). BNE flights continue to AKL, exploiting the idle time, but also likely ensuring that BNE and AKL are both served, and at higher frequency. One might argue that one or both of BNE or AKL would not be viable as a standalone service, and the tag-on and fifth freedom revenues ensure its viability. Services to SYD and MEL do not operate with a tag-on and/or fifth freedom services and are assumed to be independently viable. Furthermore, passengers for the tag-on destination would cannibalise SYD and MEL bound traffic and fifth freedom revenue would need to exceed the foregone revenue on the direct service. The higher the yield premium on the direct service (likely bolstered by the overnight scheduling) the greater the opportunity cost, and thus the less viable the fifth freedom tag-on would become. The fifth freedom service would only be viable if passengers and revenue are large independent from the direct service.

CI 57 TPE–MEL 11:30pm 11:45am+1

CI 58 MEL–TPE 10:10pm 4:40am+1

CI 51 TPE–SYD 11:30pm 11:45am+1

CI 52 SYD–TPE 10:10pm 4:40am+1

CI 53 TPE–BNE 11:55pm 10:45am+1

CI 53 BNE–AKL 12:55pm 7:00pm

CI 54 AKL–BNE 8:30pm 9:20pm

CI 54 BNE–TPE 10:50pm 5:45am+1

The third motivation is for LCCs like D7 and OD. Scheduling would otherwise not enter the equation since they would normally not schedule flights based on connecting opportunities, rather focusing on O&D traffic. Furthermore, their strategy does not require the network effects generates by higher frequency services, and their cost structure would not require the yield premium generated from higher frequency services. The viability of fifth freedom services would be determined by their market demand and supply and their relative costs advantages. They will still be hampered by limited sales and distribution capacity in the Australian and New Zealand markets. Given the relative paucity of LCC services between Australia and New Zealand, there likely exists an opportunity for LCC orientated fifth freedom traffic.

Conclusion

It is worth noting that many fifth freedom markets to/from Australia remain underutilised, not just between Australia and New Zealand, but many other markets. For example, routes between Australia and the US are open to significant fifth freedom competition due to an open skies agreement that entered into force in 2013. Carriers from several third countries could conceivable operate fifth freedom routes between Australia and the US, yet none do. These include EK and EY (the Australia-UAE BASA has no limitations on points beyond, while the US and UAE have an open skies agreement), and potentially carriers from China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, India, New Zealand, the Philippines, and Vietnam, amongst many others.

While carriers from these countries have not exploited the privileges, others have attempted to. SQ have long been interested in flying fifth freedom routes onwards to the US. In 2006, they were denied fifth freedom privileges between Australia and the US. The Australia-Singapore BASA is often described as an open skies agreement due to its lack of frequency and capacity between Australia and Singapore, but it has limits on onwards routes. Singapore has long advocated for a true open skies agreement which would remove any impediment to SQ flying onwards to the US. However, Australia favours a multilateral ASEAN open skies agreement that in addition to include open skies with Singapore, would also extend open skies to other countries in the region. While Singapore is most interested in its market access to Australia, Australia is most likely more focussed on its market access to other ASEAN countries like Indonesia.

However, it is no guarantee that SQ would exploit fifth freedom frequencies at this point. It’s previous interest was prior to the implementation of open skies, and the Australia-US market is substantially more competitive now than it was in 2006. As with the Australia-New Zealand open skies agreement, open skies has also removed constraints from the home market incumbents hold, and SQ would face a tougher time as a fifth freedom competitor than is may have in a constrained market. Furthermore, their partnerships with UA and NZ may deter them in a similar manner to how its partnerships with NZ and VA have deterred them from Australia-New Zealand fifth freedom routes. The benefit of open skies for SQ may now lie in greater integration with joint venture partners rather than fifth freedom routes.

It is often argued that opening more markets to greater competition from fifth freedom services would benefit consumers through higher capacity and ultimately lower prices. However, as this analysis has shown, the magnitude may be overstated with the outcome affected by an array of factors including networks effects and scheduling. In many cases, fifth freedom operators face significant challenges competing against incumbent home carriers and the economic incentives may not encourage large investments by fifth freedom carriers. The same challenges may apply to cabotage services. The larger public benefit lies with the removal of frequency, capacity and scope constraints of home market carriers, including those operating to/from large international connecting hubs.