Qantas Airways Limited FY24 financial results

Is Jetstar the orange/silver lining?

Qantas released their full year (July 2023 to June 2024) financial results yesterday. As expected, statutory profit, Qantas’s bottom line measure of after tax profit was down 28% to A$1.3 billion. Meanwhile, total revenue was up 11%, indicting a decline in the net margin from 9% to 6%. We say “as expected” since their half year (July 2023 to December 2023) results released in February were indicative of this trend with statutory profit down 13% while total revenue was up 12%, with the net margin declining from 10% to 8% compared to the first half of FY23.

Additionally, the weakening of international unit revenue and yields has been staring us in the face as market capacity has normalised following the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, as indicated from our analysis elsewhere, overcapacity between Australia and the United States has decimated loads. Much of this hadn’t been reflected yet in first half results published in February.

Simultaneously, regular reporting of official data on the domestic market has seen a softening with slower capacity increases being reported in BITRE passenger data over the last six months, and BITRE showing significant declines in discounted economy fares over the same period.

While profits fell, it was still an overwhelmingly positive set of results for Qantas. Unit revenues and yields are still outperforming pre-pandemic levels, while costs have remained flat despite the challenging inflation and currency environment. From a profitability perspective, margins remained very strong compared to pre-pandemic levels. Let’s take a little deeper dive into the segment performance …

Qantas domestic

Qantas domestic produced a very resilient result with unit revenue and yields increasing 2.4 and 2.6% over the full year, respectively. This was despite first half unit revenue declining 1.6% and yields increasing 0.8%. This means that second half unit revenue and yields were up 6.6% and 4.7%, respectively. This is particularly surprising as BITRE data suggested market level capacity increasing by 5% in the second half, after increasing 11% in the first half.

On the cost side, unit costs increased by 6.8%, resulting in decline in the operating margin from 18.2% to 14.7%.

Qantas international

Qantas international slumped, ultimately driving the bottom line result. Unit revenues and yields declined 14.2% and 11.4%, respectively. Again, this was not unexpected. In fact, it was somewhat better than we’d expected as first half unit revenues and yields reported in February declined 18.1% and 16.1%, respectively. This means that the second half improved to a decline of 10.7% and 7.9%.

This is somewhat unexpected since most of the dramatic over capacity between Australia and the US affected second half results dramatically more than the first half. There are two important conclusions from this:

Performance in non-US markets was still strong and that the over capacity in the US market doesn’t reflect over capacity elsewhere.

Qantas’s careful capacity management in the US market has somewhat insulated them from further unit revenue and yield declines. While Qantas have been criticised for slow capacity returns to/from the US, their pragmatic approach of pivoting capacity to other markets, particularly Asia and Europe has paid dividends.

On the cost side, unit costs increased by 9.0%, not enough to stop operating margins falling from 11.7% to 6.4%.

Jetstar

Jetstar have delivered! Several months ago we argued that Jetstar have become the saviour of the group. That way a bit of a hyperbole …

That analysis focused on international capacity and highlighted how Jetstar’s use of the A321LRs to take over shorter B787 flying to Bali was allowing their B787s to be redeployed into Asia. This was able to cover Qantas’s acute fleet shortages there, in some cases replacing mainline capacity (e.g. SYD-KIX, MEL-SIN).

Jetstar’s financial performance over the full year was sensational! While unit revenues and yields declined 7.2% and 7.6%, respectively, they did this while growing capacity (measured by available seat kilometres) by an astonishing 25.2%. You may ask how one can consider declining unit revenues and yields as astonishingly good performance?

Jetstar is a low cost carrier and so the degradation of unit revenues and yields while growing capacity would be acceptable provided it didn’t compromise the cost structure. Relative to a full service carrier they have a keener focus on cost discipline! They did better than that! Unit costs declined by 7.7%, overcoming the declining unit revenues and yields, and seeing operating margins increase from 9.5% to 10.1%!

Why is Jetstar is the orange/silver lining?

Jetstar’s performance must also be contextualised at a group level. The purpose of Jetstar within the Qantas group isn’t just to perform well on its own terms. It needs to generate synergies across the group.

On the cost side, the synergies are well understood and easy to understand. It provides the group with greater economies of scale that can benefit things like financing, aircraft procurement, maintenance, etc. On the revenue side, synergies are often trivialised to “rightsizing” routes with the ability to operate different routes on different brands, matching capacity or even target market. A typical example is Jetstar’s focus on leisure heavy routes in Southeast Asia (e.g. Bali and Phuket).

In recent months we’ve argued that the synergies are more substantial, with a strategic focus to segment traffic between the brands, shifting lower yielding traffic onto Jetstar allowing Qantas to focus on higher yield traffic. This is more deliberate and strategic than just using Jetstar’s capacity on leisure heavy routes and Qantas on higher yielding. What do we mean by this?

The first part of this is Qantas’s drift towards lower density cabin configurations. On long haul aircraft this also coincides with a drift towards smaller aircraft, although this is not the case on short haul aircraft (for a different reason). For example, over the last 7 years Qantas have introduced 14x B787-9 aircraft that ostensibly replaced the B747-400 in the fleet. Qantas have fit the B787-9 with a low density configuration carrying only 236 passengers. Meanwhile it is replacing the B747-400 which carried 364 or 353 passengers.

B787-9 C42 W28 Y166 236

B747-400A C58 W36 Y270 364

B747-400B F14 C52 W32 Y255 353

B787-9 C18% W12% Y70%

B747-400A C16% W10% Y74%

B747-400B F4% C15% W 9% Y72%On a percentage basis the differences appear trivial, but on an absolute basis the picture becomes clearer. Instead of having to sell 270 or 255 economy class seats, they now only have to sell 166; instead of having to sell 32 or 36 premium economy seats they now only have to sell 28; and instead of having to sell 58 or 66 business and first class seats they only have to sell 42.

Further reinforcing this is of the 89 or 104 fewer economy class seats (or 4 to 8 fewer premium economy seats; or 16 to 24 business and first seats), they’ll look to use the declining capacity to reduce the proportion of lower fare classes in the ticketing mix to increase unit revenue and yields.

And this is where Jetstar comes in! It might confuse the casual observer to see Qantas and Jetstar operating alongside each other on the same routes, particularly on international routes. Excluding routes to New Zealand, Qantas and Jetstar operating simultaneously to Bangkok, Denpasar (Bali), Honolulu, Nadi (Fiji), Port Vila, Seoul, Singapore, and Tokyo (Narita). Jetstar’s only international routes they don’t fly alongside Qantas are Ho Chi Minh City, Osaka and Phuket.

What this strategy does is allow Qantas to focus on generating significantly higher yields while siphoning off lower yielding traffic onto Jetstar. Not only does this happen on long haul routes but also on short haul routes (both domestic and international) where Qantas and Jetstar overlap significantly. The strategy is really staring to yield fruit!

We can examine it in more detail looking at the evolution of Qantas and Jetstar’s yields and unit costs over time. While there are many things to critique Qantas over, including governance, one can’t fault the detail of their financial reporting. It’s incredibly detailed, including segmentation of revenue, profits, and capacity by brand and even sub-segments. This detailed reporting allows us to breakdown Qantas and Jetstar’s yields and unit costs for more than a decade.

Yield is an important revenue metric for airlines, measuring revenue earned per passenger weighted by the length of each flight. The typical measure is the revenue per revenue passenger kilometre (RPK), thus excluding non-revenue paying passengers. As you might expect, Qantas’s yields consistently exceed that of Jetstar, even while following similar trends over time.

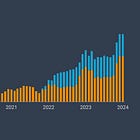

Between FY12 and FY19, Qantas yields varied between A$0.15 and A$0.17 per RPK, 64% to 78% higher than Jetstar’s yields that varied between $0.09 and A$0.10 per RPK. Yields of both carriers spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic (FY21 and FY 22) but have moderated since. While Jetstar’s yield is still 23% higher than the pre-pandemic average (FY12-19), Qantas’s is a whopping 36% higher. It’s yield premium over Jetstar now stands at 88% compared to an average of 70% during the pre-pandemic period.

But as we’ve said before, yields aren’t everything, especially to Jetstar! Qantas thrive by generating strong yields, whereas Jetstar thrive by keeping costs low. Unit cost is the metric for comparing costs between airlines and over time and typically estimates the costs per available seat kilometre (ASK). Where this is different to the yield, the denominator is all available seats weighted by distance rather than just revenue paying passengers. The difference is intuitive since empty seats still cost money to fly whereas on the revenue side an airline would rather sell one ticket for $100 than two tickets for $25 dollar each!

Between FY12 and FY19, Jetstar maintained a consistent unit cost of A$0.07 per ASK, whereas Qantas’s unit cost varied between A$0.11 and A$0.13 per ASK. Thus, Qantas’s cost base was between 62% and 85% higher than Jetstar, showing Jetstar’s clear cost advantage! Costs of both carriers spiked during the pandemic but have have declined since. Jetstar and Qantas’s costs are approximately 28% and 29% higher than he FY12-19 average.

A clear trend has emerged with Qantas growing it’s yield premium over Jetstar, while both carriers have maintained relative cost discipline. A superficial interpretation is that Qantas have outperformed Jetstar. In fact, Qantas was responsible for generating 77% of operational profit in FY24. Furthermore, Qantas’s share of operating profit has grown from between 71% and 73% in the years immediately preceding the pandemic. So how can we argue that Jetstar has been the star performer?

We argue that Jetstar has actually enabled Qantas to focus on yield generation through the market segmentation strategy shifting lower yielding traffic onto the lower cost base. This is evident when we bring capacity into the mix! Qantas’s share of group capacity has declined consistently over time, falling from 71% to 68% before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a more rapid shift has occurred since the pandemic with Qantas’s share of group capacity declining relatively rapidly to 65%.

Some might argue that the shifts are an artefact of the pandemic and fleet decision making during the pandemic. While the pandemic has had some externalities in respect of the fleet (e.g. early retirement of 2x A380s and slow pace of refurbishment of the A380s) decisions that have had a more significant impact on these trends were deliberate strategic decisions taken well before the pandemic including the withdrawal of the B747-400 and replacement with a smaller number of B787-9.

These are focused on Qantas’s capacity, but as noted earlier the impressive performance of Jetstar was how they were able to increase their operating margin while increase capacity an astonishing 25.2% in the last year. The enabler of this was the delivery and entry into service of the A321LR that enabled the A321LR to take over a lot of B787-8 flying allowing Jetstar to redeploy these onto longer routes into Asia, in most cases operating alongside Qantas and in some cases even replacing Qantas capacity (e.g. Osaka).

This strategy is not lucky or opportunistic but rather reflects a deliberate and well-considered long term strategy to segment traffic across the two brands, but more importantly across two cost structure. While this has been occurring on domestic and short-haul routes for many years, however the recent trends show an expansion of the scale of this segmentation on international routes.

Consequences now and into the future

The importance of this increasing segmentation of international flying is highlighted by looking at the difference between Qantas’s domestic and international unit revenues, yields and margins. Unfortunately, the financial statements don’t allow this segmentation of Jetstar’s earnings. What is clearly evident is how Qantas’s domestic operation is significantly more profitable than its international operations. In many respects, international is the laggard in the group and has been for years.

Changes brought about under Alan Joyce’s leadership brought about dramatic turnaround in Qantas’s international fortunes. The recalibration of the perennial loss-making European routes brought international into consistent profits, but it still lags domestic performance. This was evident between FY17 and FY19 where domestic margins grew while international margins declined.

It remains to be seen if the improved post-pandemic margins for Qantas international are sustained, but we are optomistic that the impact of increased segmentation between Qantas and Jetstar on international routes will sustain the improved Qantas international’s performance by helping them maintain higher yields going forward. This is certainly something to monitor as Jetstar are likely to continue reinforcing international capacity with eight more A321LR due in FY25 and four more in FY26.

Thanks for the write up. Jetstar Japan improved its statutory loss from $54m to $16m (net to QAN), despite a $19m net impact from depreciation in the Yen, which is a big underlying swing. JS Asia is increasing capacity 50% in FY25 although its unclear how much, if any, applies to Japan. Do you prospect Qantas could actually see benefit - cash or kind - back from this investment?