Sydney single runway operation on 5 October 2023

Sydney (SYD) airport has well publicised operational constraints including a nighttime curfew and a cap of 80 aircraft movements (arrivals and departures per hour). It operates three runways, the parallel 16/34 runways, and the “cross-wind” runway 7/25. These runways are used in several different combinations resulting in several different operational “modes”. Particular modes are preferred during certain times of the day due to noise mitigation procedures, for example, “mode 1” using 34L for arrivals and 16R for departures is the preferred mode during the curfew (during which a limited number of operations are allowed). When weather conditions necessitate the use of some modes, a reduction in aircraft movements is required. This includes when intersecting runways or a single runway are in operation.

Yesterday (5 October 2023), strong and gusty westerly winds required the use of runway 25 for both arrivals and departures at times (mode 13), although other modes were also used throughout the day. This necessitates a reduction in the number of aircraft movements. Planning starts well in advance when Air Services Australia release the Air Traffic Flow Management Daily Plan (ATFM). Version 1 is released the evening before and establishes an hourly “flow rate”, or the number of arrivals that SYD can accept each hour, based on the expected runway mode in operation during each hourly block. The flow rate balances arrivals and departures, with the total number being roughly equal throughout the day, although the balance between arrivals and departures may differ during each hour. At approximately 6am, an updated version 2 is released that takes into account updated weather and consequently potential adjustments to the runway modes in each hourly block. Importantly, it also updates planning with expected arrival times for the now significant number of long-haul flights that are now in the air and had not yet taken off at the time of version 1. For example, yesterday’s first scheduled arrival was QF 2 from LHR via SIN at 6:10am. It departed SIN at 2:55am AEDT, well after the finalisation of version 1, with it’s expected arrival time being 10 minutes earlier than scheduled. BA 15, also from LHR via SIN was also scheduled to arrive at 6:10am, but has departed SIN late, and is now expected at approximately 7:10am. Thus, version 2 refines the availability of and the demand for arrivals slots as expected arrival times get updated (compared to scheduled arrival times). The ATFM is not cast in stone, and the flow rate may be increased or decreased at any given time based on the actual conditions.

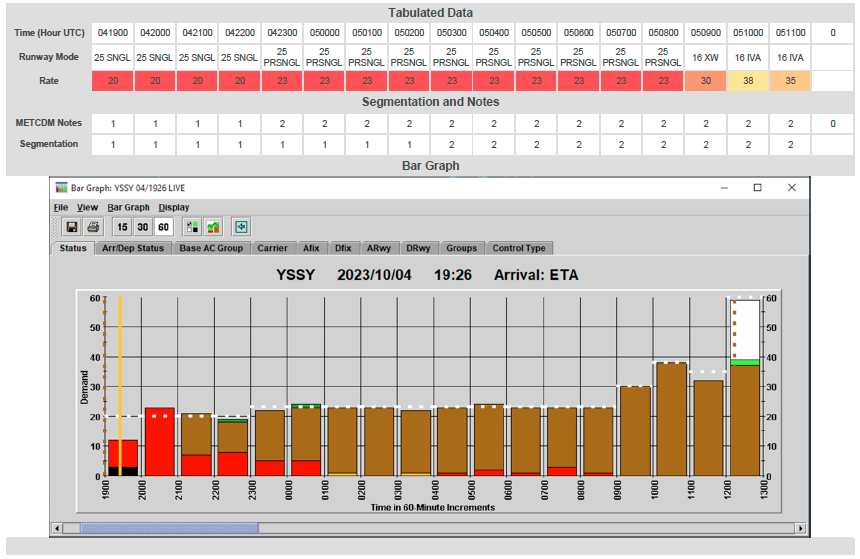

Yesterday, version 2 established an arrival rate of 20 aircraft per hour until 10am, 23 aircraft per hour until 8pm, increasing thereafter (see Figure 1). Furthermore, in addition to the weather staffing constraints also generated some limitations between 9am and 11am. This is roughly half the normal flow rate under optimal conditions. Airlines are expected to reduce their demand for arrival slots accordingly. International airlines are less affected due to fewer number of total flights. In practice, it would be “unfair” to force an airline with a single daily flight to cancel the flight given their limited ability to re-accomodate passengers through other means. The burden falls on the airlines with largest number of flights, in this case Qantas, Virgin, Jetstar, and Rex. The burden is not evenly applied, since the number of slots that each must give up depends when those slots are. Since demand for slots varies within the day, particularly for different types of flights, the impact might be felt harder on an airline if they operate a larger number of flights at times when demand is higher.

For example, in the early morning, demand for arrival slots from long-haul flights is relatively high meaning that Qantas, Virgin, Jetstar, and Rex are likely going to see a greater burden during this time. Furthermore, Qantas also has a relatively large number of early morning arrivals, for example, yesterday, 23% of Qantas‘s scheduled arrivals for the day were between 6am and 9am, compared to just 10% and 15% for Jetstar and Virgin, respectively. This means that they will potentially share a relatively heavier burden than Jetstar and Virgin. But since many of Qantas‘s early morning arrivals are long-haul flights they may face even more pressure to reduce their demand.

Airlines can reduce their demand for slots in two different ways. Obviously cancelling a flight reduces the need for a slot, but airlines can also delay flights, cascading flights later in the day to when demand may be less than the maximum flow rate. They may hope that weather conditions improve allowing an increase in the flow rate, or other airlines face greater delays that open slots. Airlines also have different strategies and capacities to mitigate the challenges, including rebooking connecting passengers through other hubs to reduce demand for SYD flights, or increasing the gauge of existing flights. For example, Qantas may consolidate two SYD–MEL flights into one by operating a larger aircraft (SYD–MEL flights are typically operated at high frequency with 174 seat B737-800s; whereas Qantas also operate the larger A330-200 (251 or 271 passengers) and A333-300 (297 passengers)).

Who handled yesterday better?

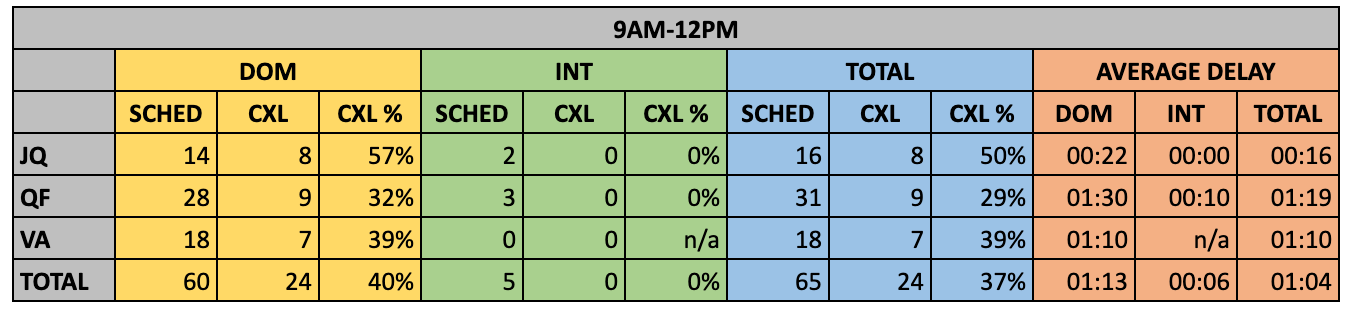

So how did the airlines handle this yesterday? We tracked all Qantas, Jetstar, and Virgin arrivals yesterday using ADS-B data (passenger flights only). Of the 333 scheduled arrivals, 73 were cancelled (22%), with the remaining 224 flights operating with an average delay of 47 minutes (see summaries for the whole day as well as 3 hour blocks in the tables below. Throughout the course of the day, all three had a similar cancellation rate, although Qantas was lower than the average (19% compared to 22%), with Virgin and Jetstar suffering higher cancellation rates of 26% and 24%, respectively. However, Qantas a higher average delay (56 minutes compared to an average of 47 minutes), while Virgin and Jetstar achieved average delays of 44 and 28 minutes, respectively. One might argue that Qantas traded cancellations for delays, cancelling fewer flights, but operating with larger delays as a result. While a delayed flight is inconvenient, it is somewhat less inconvenient than a cancelled flight. On this basis, some may argue that Qantas outperformed, with its significant lower cancellation rate. However, the aggregated view of the day obscures some of the within day variation, and the operational constraints that each airline faced.

Given Qantas‘s higher share of morning arrivals, we might expect a higher cancellation and/or delay rate during the 6-9am block compared to Virgin or Jetstar. However, since many of those arrivals (13 of 39) were international flights, Qantas‘s cancellation rate was only 23% during that block, compared to 60% and 62% for Jetstar and Virgin, respectively. Notably, no international arrivals operated by Qantas, Jetstar, and Virgin were cancelled yesterday, highlighting how the burden on domestic flights. A consequence for Qantas was more flights being delayed, and being delayed for longer Virgin and Jetstar. Essentially, Qantas traded cancellations for delays, while Virgin and Jetstar traded delays for cancellations.

Moving to the 9am to noon block, Qantas cancelled more flights, ostensibly since earlier delayed arrivals were now cascading into later blocks, cannibalising increasingly scarce arrival slots. Increasing cancelations now were required in order to reduce the likelihood of increasing and cascading delays. Conversely, Virgin and Jetstar were able to reduce their cancellation rate as they were not suffering from the cascading delays to the same extent as Qantas. This goes a long way to identify why Virgin and Jetstar had such a high cancellation rate in the morning block, effectively proactively trading delays for cancellations to protect the integrity of the operation. Qantas had less latitude to do this given the larger number of long-haul arrivals. As the day progressed, cancellation rates stabilised somewhat, as did average delays.

Obviously, nobody wants their flight delayed, although one might argue that a delayed flight is better than a cancelled flight. A delayed flight is frustrating, and it’s common to see passengers taking to social meeting to vent their frustration, comically sharing anecdotal evidence that other flights arrived or took off on time. Indeed, through all the carnage yesterday, some flights arrived on time, and some even arrived early. To some extent, this is the luck of the draw.

Different airlines have different constraints, balancing their scheduled slots with ATFM flow rate requirements alongside their own operational constraints and capacity. Simply put, Virgin cannot suddenly increase the aircraft size, and Qantas can’t cancel a long-haul flight already in the air. However, we see from the data how different airlines handled the situation and the obvious trade-offs. From the outside, it is difficult to know how well airlines handled the operational situation (ignoring how well or poorly airlines handled the customer service element), but it does appear from the data that all three airlines adopted different strategies, adapted to their network and capabilities. While there were many delays and cancellations, a cancellation rate of 22% when the ATFM was estimating a flow rate of approximately 50% highlights how well the airlines and ATC performed under the circumstances. Furthermore, the lack of cascading delays and cancellations through the day is testament to proactive planning.