Vietnam and Turkey show Qatar how to go about it

Several months back, we covered the rather aggressive and public approach that Qatar Airways (QR) took in their engagement with the Australian government in seeking additional market access to Australia. Their strategy focused on a concerted media campaign that attempted to lay blame on the feet of Qantas Airways (QF) and Catherine King, the Minister for Transport.

The campaign exploited the public outrage targeted at QF and then CEO Alan Joyce due to their perceived poor performance during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. It culminated in a Senate enquiry during which QF admitted to lobbying the government in opposition to QR. Some commentators described the media coverage as a pile-on on QF, while the media ignored that most carriers seek to protect market access.

We argued that QF were unlikely to gain significantly from denying QR additional market access and that other carriers, including Singapore Airlines (QR) and Emirates Airline (EK) were the most significant beneficiaries. The data supporting this argument was that too little of QF capacity was focussed on routes beyond Doha (DOH) and that the bulk of QF‘s capacity was focussed elsewhere, particularly Asia and the Pacific.

We also highlighted that QR were seemingly negotiating directly with the Australian government. This appeared unusual since Bilateral Air Service Agreements (BASA) are agreed to between governments, not airlines, and that they formed part of broader diplomatic engagements. As with any negotiation, compromise is achieved when both parties make concessions to achieve an outcome of mutual interest.

Expansion of capacity to Vietnam and Turkey

The most recent update (December 2023) by the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Local Government shows two notable expansions of BASAs.

Capacity between Vietnam and Australia has been increased considerably. Previously, each country were limited to 35 weekly frequencies between Vietnam and Sydney (SYD), Melbourne (MEL), Brisbane (BNE) and Perth (PER). An additional 7 weekly frequencies were available provided they operated via or beyond to another point in Australia (other than SYD, MEL, BNE or PER). Furthermore, capacity to points other than the four main gateways was unrestricted, and there were no limitation on aircraft types, seat capacity or the distribution between cities.

Capacity to the four main gateways has now been increased from 35 to 49 weekly frequencies, and will increase further to 63 and 77 per week from the end of October 2024 and 2025, respectively.

Capacity between Turkey and Australia has also been increased considerably. This is notable since there are no scheduled flights between Turkey and Australia at present. In the case of Vietnam, all frequencies available to Vietnam have been allocated to Vietnam Airways (VN), VietJet Air (VJ) and Bamboo Airways (QH), and are presently utilised. QH recently cancelled all long haul flying and their frequencies will likely be reallocated to VN and/or VJ in due course.

Previously, Australian and Turkish airlines were limited to 7 weekly frequencies between Turkey and SYD, MEL, BNE and PER. This placed a limitation on Turkish Airlines (TK) who wished to serve both MEL and SYD daily. TK argued that less than daily frequencies undermined the viability of the flights. The updating of the BASA has extended capacity from 7 to 21 flights per week with immediate effect, with further increases to 28 and 35 weekly frequencies from the end of October 2024 and 2025, respectively.

This will allow TK to serve both MEL and SYD daily, with the opportunity for expansion to BNE and PER, or increasing frequencies to MEL and SYD to multiple daily frequencies. The updated agreement clarifies the use and placed some limitations of fifth freedom services.

Implications of the expansions

The expansion of the agreements have significantly different implications given the different strategies of the incumbent airlines as well as the geographic locations of Turkey and Vietnam, as well as the different bilateral relationships between Turkey and Vietnam, and Australia.

The Vietnamese-Australian market has grown and is expected to continue growing rapidly, driven by a multitude of factors, including:

According to the 2021 census, there were 257,995 people in Australia who were born in Vietnam, accounting for 4% of all people born outside Australia. 59% have been in Australia for more than two decades, indicating a larger community of second and third generation Vietnamese in Australia.

Outbound tourism, including Vietnamese Australians visiting family and relatives, and Australian tourists to Vietnam have increased considerably. ABS data shows that annual outbound tourist numbers increased from 165,140 to 317,090 between 2008 and 2019.

Inbound visitors from Vietnam have also increased considerably, with the same ABS data showing annual inbound short term visitors to Australia from Vietnam increasing from from 31,610 in 2008 to 123,460 in 2019.

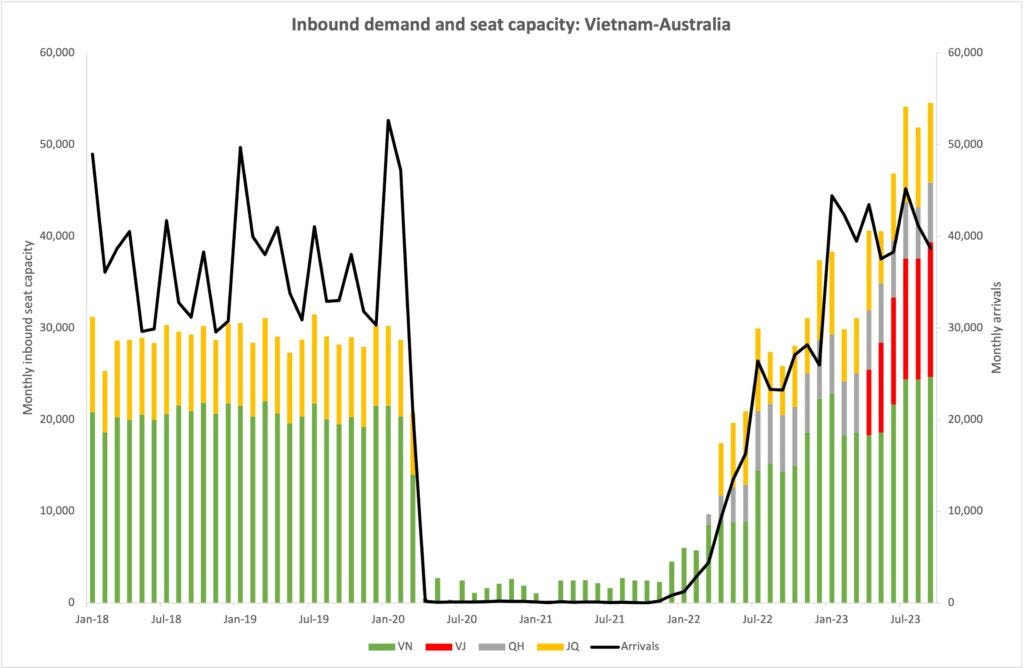

In recent months, flights to/from Vietnam have begun to carry considerably more onwards connecting traffic as data from our Capacity Tracker shows that inbound seat capacity generally exceeds inbound demand (combination of short term arrivals and returning residents using ABS data) whereas the pre-pandemic showed inbound demand exceeding seat capacity.

Arguably, this is a more significant threat to QF given the significant scope that VN and VJ have for connecting traffic to/from large and important markets throughout Asia (e.g., China, India, etc). The exceptionally low cost base that Vietnamese carriers enjoy in comparison to QF gives them significant advantages.

The entry of TK into the Australian market can be considered alongside the broader market of westbound stop-over carriers, but also in the context of the significant Turkish immigrant population in Australia. While smaller than Vietnam, it is significantly nonetheless. TK have developed into a significant stop-over carrier, rivalling the capacity and scale of QR, EK, and Etihad Airways (EY).

TK also have a significant comparative advantage over QR, EK, and EY in that their Istanbul (IST) hub is located somewhat closer to Europe, allowing connections to a larger number of secondary cities at higher frequencies by utilising narrowbody aircraft on these sectors.

Furthermore, the significantly larger O&D market between Europe and Turkey results in more favourable market access, with Turkey enjoying open skies access to the EU. For example, in Germany, TK enjoy open skies whereas EK suffer from significant capacity constraints. Arguably, this presents a more significant threat to QF than QR given TK‘s unlimited market access at the destination.

The lesson

Unlike Qatar, Turkey and Vietnam did not litigate the issue in public, nor did they attempt to negotiate through the media. QR‘s strategy caused significant embarrassment to the Australian government. Whether this was the intent, one might argue that it was tantamount to using bullying as a negotiating strategy. It has not, as yet, resulted in any concession from the Australian government.

As BASAs are negotiated alongside broader diplomatic activities, it is not clear how litigating the negotiation in public and through the media serves to advance discussions between Qatar and Australia where Australia may seek a concession in return in another areas of interest (e.g., potentially on trade policy or military cooperation). This is somewhat important given that there have been areas of disagreement between Australian and Qatari diplomats in recent months.

On the other hand, Turkey and Vietnam took alternative approaches. While TK did discuss the issue in the media, they made no attempt to criticise or pressure Australia, whereas there has been no discussion even of the expansion of the Vietnamese rights in the media until this week.

One might also consider two counterfactuals. On the one hand, you may argue that none of this matters. BASA rights are entirely political and that countries come to agreements favouring allies. Australia is simply favouring Turkey and Vietnam at present for purely political or strategic reasons. However, if that were the case, then QR‘s actions were entirely pointless to begin with.

Secondly, one might argue that countries take purely technocratic decisions based on actual capacity needs. Again, in that case, Australia’s decision would be purely rational. We raise these counterfactuals since there is an element of truth to both, and one cannot discount the role of politics and actual needs in the development of BASA policy over time.