How to think, not feel about Qantas's Project Sunrise

Project Sunrise, the much vaunted strategy by Qantas to fly non-stop from the eastern seaboard of Australian to London and New York finally looks like coming to fruition in 2027. First announced in 2017, and originally slated to start in 2022, the first A350-1000ULR that Qantas acquired for Project Sunrise will arrive in late 2026. The first Project Sunrise flight - presumably Sydney to London - will likely take place at the start of NS27 season in March 2027.

Many observers initially labeled Project Sunrise a publicity stunt. Even Cam Wallace, currently the CEO of Qantas International but then an executive at Air New Zealand, initially wrote it off as one. Qantas are very, very good at PR, so it’s easy to be cynical about it. However, recent history has shown Qantas’s ambitions to push the envelope on ultra long haul (ULH) flying. In the last decade, Qantas have launched several new ULH routes, each significantly longer than their previously longest flight from Los Angeles to Melbourne. Qantas’s push into ULH flying was enabled by their acquisition of the B787-9 that allowed them to extend flight times by nearly two hours.

Route Distance Block* Start

PER-LHR 7829nm 17:50 2018

DFW-MEL 7814nm 17:40 2022

PER-CDG 7702nm 17:30 2024

JFK-AKL 7671nm 17:40 2023

DFW-SYD 7454nm 17:25 2014**

PER-FCO 7211nm 16:25 2022

LAX-MEL 6883nm 15:55

* Block time of longest/westbound leg.

** Prior to 2014, westbound leg was operated via BNE.In some respects, it’s not surprising to see Qantas pushing the envelop once again. We wanted to understand why they’re doing this? What’s motivating them in pushing block times to 21 or 22 hours that’ll be required for the westbound Sydney-London sector?

We’re not interested in how people feel about it, rather we’re interested in cutting through the nostalgia, resistance to change and spin, to understand the strategy and economics behind it. There’s a lot more nuance than meets the eye, so we wanted to challenge some of the simplistic narratives and understand the costs and risks involved, and the prize.

This analysis is very long, so apologies in advance, but there are a range of factors, and a whole lot of history that needs to be understood to help us reach an incredibly provocative conclusion: the tyranny of distance and the inability to compete on cost with one-stop carriers means they don’t have much of a choice other than a “deal with the devil”!

How people feel about it

Didn’t we just say we’re not interested in how people feel about it? We did, but let’s allow ourselves a short digression to reinforce why “how people feel” about it isn’t interesting or important. We know this sounds condescending, but bear with us.

Social media is a cesspool of engagement farming these days and Project Sunrise has been perfect fodder for asking people how they feel about 22 hour non-stop. The replies are just what you’d expect, with a lot of strong feelings about not wanting to do it. The algorithm will boost negativity and have us believe that the overwhelming opinion is that people hate the idea.

We’ve seen this before though. For those of us old enough to remember, there was a time when most long haul flights required several fuel stops. These have declined over time as aircraft technology improved. Old hands remind us how people bemoaned when flights like Melbourne-Los Angeles or Sydney-Johannesburg went non-stop following the introduction of the B747-400. Or how the 2nd stop was dropped from Sydney-London (and presumably the 3rd, 4th and 5th stops before that). These are now a distant memory, and most contemporary passengers would cry foul if any airline suddenly reintroduced a fuel stop in Fiji or Mauritius!

Los Angeles is no longer the frontier either, with non-stop flights to the United States now targeting more efficient connection hubs further afield (e.g. Dallas and Houston), providing passengers with more efficient connections to a wider range of destinations in the US. Really, who the hell wants to transit at LAX if you can avoid it?!?!

Nostalgia is powerful aphrodisiac and it’s hard to change the mind of someone who “feels” strongly about it. Qantas continue to shift capacity from Los Angeles and San Fransisco to Dallas, while American (Dallas) and United (Houston) have followed suit. We can only suppose they’re doing this because they’re following what customers want rather than strong feelings on social media.

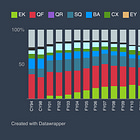

As an aside, have a look at a short “chart of the week” we published earlier this year showing how patterns between Australia and the US have evolved over time.

More importantly, we’ve also seen a comparable evolution of flights between Australia and Europe, beginning with Qantas shifting the stopover point on their Melbourne-London flight from Singapore to Perth in 2018. Technology played a big role in this with the introduction of the B787-9 allowing Perth-London to be flown non-stop. The Perth-London sector has been so successful that Qantas dropped the Melbourne leg in 2024.

Our analysis at the time showed that the share of Melbourne passengers declined consistently as the non-stop Perth-London leg became more popular over time. By 2024, Melbourne O&D passengers accounting for one-fifth of the total passengers while the flight boasted load factors of well above 90%. Quite frankly, nobody predicted this was an outcome in 2018.

Qantas have since introduced other non-stop flights from Perth to Europe: a seasonal 3x/week Rome flight and more recently 3x/week to Paris. The success of Rome has led Qantas to announce a 4th weekly frequency and a longer operational season in 2026.

Feelings and nostalgia aside, it seems the median Qantas passenger either prefers these non-stop flights or at the very least is ambivalent about it given the plethora of alternate options, whether that be one-stop flights to Europe or connecting through Los Angeles or San Francisco.

Analytic Flying is a reader-supported publication, so please subscribe. See our ethical paywall policy to understand if you need a paid subscription (incl. industry professionals and readers using for commercial purposes).

Putting feelings aside, what is Qantas’s strategy?

Some question whether or not Project Sunrise is a huge risk for Qantas. They’re spending a lot of money on at least 12 purpose built and highly customised aircraft. The more customised an aircraft, the greater their residual risk (i.e. risk that the resale value of the aircraft declines very quickly).

Conceptually, the more customised an aircraft is the more likely it is that residual values are likely to be lower as there will be fewer buyers for them on the secondhand market. Furthermore, previous attempts to stretch the range of aircraft have rendered them significantly less efficient and less suited to deployment elsewhere in the airline’s network.

And finally, the high cost of operating ULH flights requires much higher yields and unit revenues, not just to compensate for the higher costs, but to increase margins. It’s a point of nuance, but Project Sunrise needs to outperform incumbent routes to justify the risk. Simply matching the performance of incumbent routes doesn’t justify the capital expenditure and risk!

Let’s consider these two constraints in more detail. We’ll deal with the fleet question first, and come back to yield, revenue and cost after.

Fleet: the A340-500

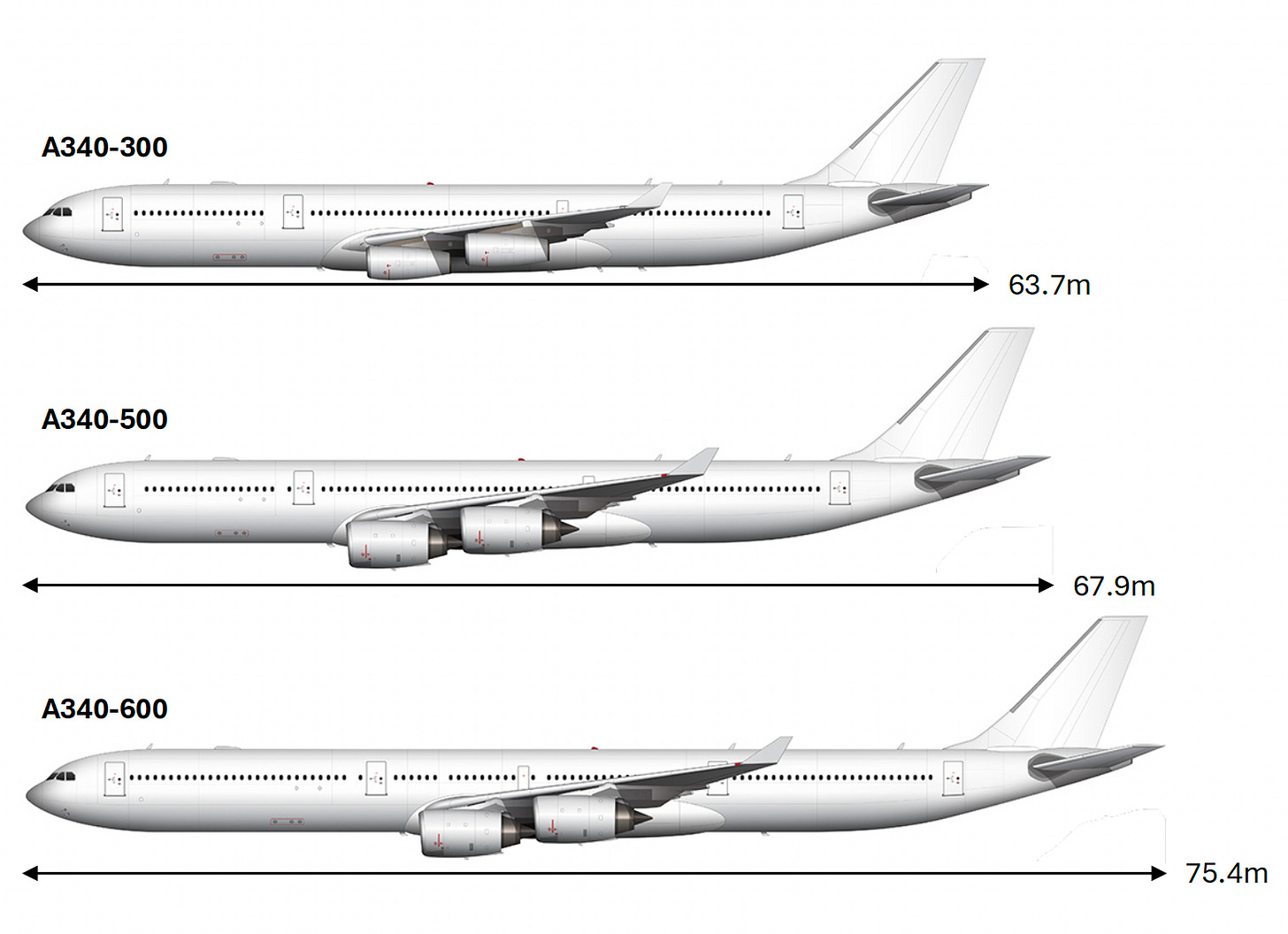

We need to take a step back into history and revisit the A340-500. The A340-500 was a progenitor of the current generation of ULH aircraft and its failure has important lessons for contemporary ULH strategies.

It was first introduced in 2002 and is a “shrink” of the A340-600, made shorter by removing several frames from the fuselage, but kept the rest of the structure and wings, and a very similar engine. The resulting aircraft was significantly smaller than the A340-600, making it a similar size to the A340-300, but because it shared the A340-600’s bigger wings, engines and fuel capacity, it lifted a much larger fuel load and carried it over an incredible distance. But there was a catch: while the burned fuel like the A340-600, it carried a similar payload to the A340-300!

It was a niche aircraft and only a handful of carriers ordered it, most notably Thai Airways and Singapore Airlines who were the only carriers operating them on ULH routes. Emirates and Etihad also ordered them, albeit not operating them on ULH routes, instead utilising its lifting power.

In order to operate it on ULH routes, Thai and Singapore both required very low density configurations. Thai introduced it with 215 seat configuration with only 53% of the seats in economy class (C60 W42 Y113). Comparatively, their B747-400s had a 84% economy class density. Singapore went with a straight 100 seat business class configuration.

Thai and Singapore’s low density cabin was not a choice, rather forced on them by payload restrictions required to enable non-stop flights from Bangkok and Singapore to New York. Just shrinking the A340-600 wasn’t enough to enable the non-stop flights and both airlines required a limited payload to make the trip. A secondary consideration was that the premium heavy cabins enabled higher yields and unit revenues to overcome the higher costs (more about that later).

Reinforcing our initial framing, this meant the A340-500 was a niche aircraft. The low density configuration made it difficult to utilise elsewhere in the network, effectively making them orphan fleets. But it wasn’t just the the configuration but also the higher fuel burn on comparative sectors. Let’s put this in perspective:

We previously noted that the A340-500 was a shrink of the A340-600, giving it a similar size to the A340-300, but with the fuel capacity and lifting power similar to the A340-600. See the scaled image below showing the lengths of the three aircraft remembering that they had the same cross section.

The implications are profound: while the A340-500 has a similar maximum payload to the A340-300 (54t versus 52t), it has a much higher structural weight with an indicative OEW (operating empty weight) of 168t, 37t higher than the A340-300 (131t). The heavier structure was required to carry the larger fuel load required for ULH flights. For comparison, its maximum fuel capacity is 175t, compared to just 110t on the A340-300.

This means that the A340-500 is carrying an extra 37t of structure for just 2t more potential payload. Unless you need that extra structure to carry fuel for an ULH flight, you’re carrying 37t of deadweight around your neck!

Meanwhile, when carrying the extra structural weight on the A340-600 (OEW 174t), you’re also able to carry a much larger potential payload (66t). The extra 12t or 14t of payload makes it more worthwhile as you can generate more revenue to overcome the higher costs! The net result is that the A340-500 is a gas guzzler, and unlike the A340-600 it’s not guzzling the fuel to carry more payload, but simply to fly further.

Rough estimates put the A340-500 and A340-300’s fuel burn at about 8.0t and 6.5t per hour in cruise, meaning the A340-500 burns 23% more fuel than the A340-300 on a comparable mission. But as we’ve just observed, it doesn’t carrying 23% more potential payload. It burns 23% more fuel to carry just 4% more payload and highlights why it made it cost prohibitive to operate the A340-500 on anything other than ULH sectors.

A few years down the line, Thai (2012) and Singapore (2013) ended their ULH flights and withdrew the A340-500s from service. They were unable to generate the necessary yield and unit revenue premium to make these flights viable. The aircraft were too expensive to utilise elsewhere in their network and, absurdly, it was cheaper to park relatively young aircraft than fly them elsewhere. They were less than 10 year old at the time!

Fleet: enter the A350-900ULR

After a 5 year hiatus, Singapore returned to ULH flights in 2018. It’s doubtful that the market changed that much of the 5 years, i.e. beyond cyclical variations in demand, it’s doubtful that customers were willing or able to pay significantly more for it in 2018 than 2013. Instead, the change has been on the cost side, with the significant improvements that the A350-900ULR offered. Let’s consider the aircraft in more detail.

The A350-900ULR’s long range capability isn’t generated by shrinking the aircraft like the A340-500. Rather, it took the A350-900 and significantly increased its fuel capacity while making a more typical trade of payload for range. This was achieved without larger fuel tanks, but modifications to the aircraft’s fuel system, including structural and software modifications allowing greater utilisation of its existing fuel capacity.

This means that the A350-900ULR doesn’t have the exaggerated fuel burn of the A340-500. In fact its fuel burn is similar to the baseline A350-900. Two A350-900s (one baseline and one ULR) with the same payload and fuel load will burn a nearly identical amount of fuel on the same route.

Let’s look in more detail:

Singapore’s A350-900ULRs have a MTOW of 280t. If it carries it’s maximum fuel load of 129t its usable payload is just 16t (using an indicative OEW of 135t).

While the baseline A350-900 has several MTOW options, let’s use the same 280t MTOW version to allow a like-for-like comparison. Its maximum fuel load is just 108t and assuming the same OEW of 135t, its usable payload would be 37t.

Note, the A350-900 is now available with a higher 283.9t MTOW, however 280t was the highest option when Singapore’s ULRs were manufactured. Presumably, they’d take the higher version now if they were ordering the ULR now. For the sake of the comparison we’ll stick with 280t.

So the A350-900ULR can carry 21t more fuel, but that costs 21t of payload. It’s a sizeable tradeoff since every 1t of extra fuel the ULR carries compared to the baseline A350-900, 1t of payload is given up. This clearly shows how the A350-900ULR is trading pure payload to carry the fuel, but they’re doing this without compromising fuel burn.

You may have noticed that there’s an externality to this. In trading off payload to carry the fuel, it’ll significantly limit the number of passengers that the aircraft can carry on ULH missions, far more significantly than the A340-500, but it’ll be a whole lot cheaper and less risky to do it!

“There’s no such thing as a free lunch”, but at least lunch is a lot cheaper flying the A350-900ULR compared to the A340-500.

The trade-off means that the A350-900ULR will still have to utilise a premium heavy, low density configuration. Singapore’s A350-900ULRs carry just 161 passengers (C67 W94). For comparison, Singapore also operates baseline A350-900s in medium and long haul configurations, carrying 303 (C40 Y263) and 253 (C42 W24 Y187) passengers, respectively.

While the operational and trip costs of the A350-900ULR will be comparable to the baseline A350-900s, they will be constrained by the configuration. This would still limited its ability to be deployed elsewhere across the network, however doing do would only be limited by cabin configuration, and not fuel burn like the A340-500.

Importantly, it has relatively lower residual risk. If the ULH routes fail, the A350-900ULR could be converted into a baseline A350-900 following a cabin reconfiguration and some software update, both things that an airline would do several times during the course of its normal working life. So if there’s a dramatic market shift or the project just doesn’t work, they’re not left with an expensive aircraft corroding away in the desert.

It would be remiss of us not to note the A350-900ULR’s limitations. Even with its much larger usable fuel load, Singapore’s configuration isn’t just a function of their desire to generate higher yields and unit revenues, but also its operational limitations. Its fuel capacity isn’t infinite and 161 passenger configuration is limited by the payload restrictions required to carry the larger fuel load. Simply put, it’s not making the non-stop trip with 200 or more passengers, so reducing density is a necessity, thereby generating a range of externalities including Singapore’s limited ability to generate higher utilisation by rotating aircraft through the network. So you don’t see Singapore sending the A350-900ULR on shorter runs to Bangkok or Jakarta during the day other than IROPS or AOG scenarios.

Fleet: enter the A350-1000ULR?

So if the A350-900 worked for Singapore, then why didn’t Qantas just copy them? Quite simply, it doesn’t carry enough fuel. Sydney-London is 900nm further than Singapore-New York, and additional payload restrictions would’ve been catastrophic! And even if it carried more fuel, what would the remaining payload be? Rough guess is that it would’ve been close to zero!

Qantas needed a new aircraft. While they considered various options from Airbus and Boeing, they chose the A350-1000ULR. We’re not going to analyse the choice of the A350-1000ULR against its competitors. It’s a sunk cost, so there’s limited value from considering the advantages or disadvantage of one or the other.

The A350-1000ULR bears similarities to the A350-900ULR. Airbus have used the same playbook to increase the aircraft’s fuel capacity. Initially it was thought that the increase in usable fuel would be achieved using the same fuel system modifications, however it’s now confirmed that the A350-1000ULR will also sport an additional fuel tank. The RCT (Rear Centre Tank) is a permanent fixture and similar in design to the RCT used on the A321XLR, albeit a lot bigger, carrying an additional 16t of fuel.

When combined with a boost in the MTOW to 322t, the A350-1000ULR’s range will be extended sufficiently without requiring the extremely low density cabin that Singapore requires on their A350-900ULRs. This doesn’t mean Qantas can deploy a similar cabin density to their other long haul aircraft like the A380 and B787-9, rather that it has somewhat more flexibility than Singapore.

Qantas will deploy the A350-1000ULR with a 238 seat configuration with 59% economy class configuration (F6 J52 W40 Y140). This compares to 70% economy class configuration on their A380s and B787-9s (notably, airlines tend to maintain a similar premium mix across their long haul fleets). Comparatively, Singapore’s economy class configuration varies between 70% and 74% on their A380s, B777s and long haul A350s, yet they have no economy class on their A350-900ULR due to operational necessities.

This gives Qantas a more versatile aircraft, while also reducing operational risk and increasing flexibility compared to Singapore as it’ll be easier to deploy it elsewhere across the network . Similar to Singapore, residual risk is reduced as the aircraft can be reconfigured and integrated into the regular fleet if needed. Just a reminder, Qantas have an additional 12 non-ULR A350-1000s on order with additional options to replace the A380s in the next decade. This highlights and reinforces the existing economies of scale and reduced residual risk.

In the same way that we considered the externalities of Singapore’s ULRs, we should consider the same for Qantas’s ULRs. The most significant externality isn’t the cabin density. In fact we’d consider that an advantage compared to Singapore’s strategy. The externality is the higher structural weight of the A350-1000ULR due to the RCT. While it’s not in the same realm as the A340-500, it can’t be ignored. Unfortunately, the specific weight of the RCT hasn’t been published by Airbus yet, limiting our analysis in this regard.

Prices, yields and unit revenue

Is Project Sunrise a bet on whether or not people will pay higher prices for a non-stop flight? It’s a popular narrative, but somewhat of an oversimplification.

Qantas have been open about how they expect to generate a 20 to 30% revenue premium, but this has been misinterpreted as 20 to 30% higher prices. They’re not the same thing! So how do they generate a 20 to 30% revenue premium without increasing prices by 20 to 30%? Higher yields, right?

“Yield” is one of the most misused term amongst avgeeks, mostly because it’s often confused with “unit revenues”. A typical example is when our dear friend Caleb says Airline X should fly so-and-so route because it’s “high yielding” and, as all avgeeks know, high yielding means it’s a sure thing, right? The only more egregious use of terminology is when passenger load factors as used as evidence of a route being successful.

By themselves, yield and load factor are meaningless! You can fill any route, generating a 100% load factor if you sell tickets cheaply enough. Alternatively, you can generate stellar yields with just one passenger. Both routes will fail miserably, so Caleb’s strategy of just flying high yielding routes isn’t going to work, nor will the alternative of maximising load factor. However, a route with high yields and a high load factor will be very successful, because high yields combined with high load factors generates high unit revenues! But what do these terms even mean?

Yield is the revenue earned per passenger, often weighted by distance to allow comparison across routes (i.e. revenue per revenue passenger kilometer). It should now be obvious that yield by itself is problematic, since if you only sell one ticket on the flight but sell it for an incredibly high price, you’ll have a very high yield. And that’s where unit revenue comes in, instead of dividing revenue by passengers, it divides revenue by the available seats on the aircraft (i.e. revenue per available seat kilometer).

Meanwhile, the load factor is simply the number of passengers divided by the number of seats available. A keen mathematical eye (read: high school maths) would notice that unit revenue is the product of the yield and the load factor. All else held constant, maximising unit revenue is what maximises the airline’s revenue on a flight, not yield or load factor by themselves.

When trying to maximise unit revenue, or at least increase it, the airline needs to either increase the yield or the load factor. In the real world, yield and load factor are not independent of each other. Increasing the load factor often involves a trade-off with yield as you will likely have to sell more cheap tickets to increase the load factor, thereby reducing the yield.

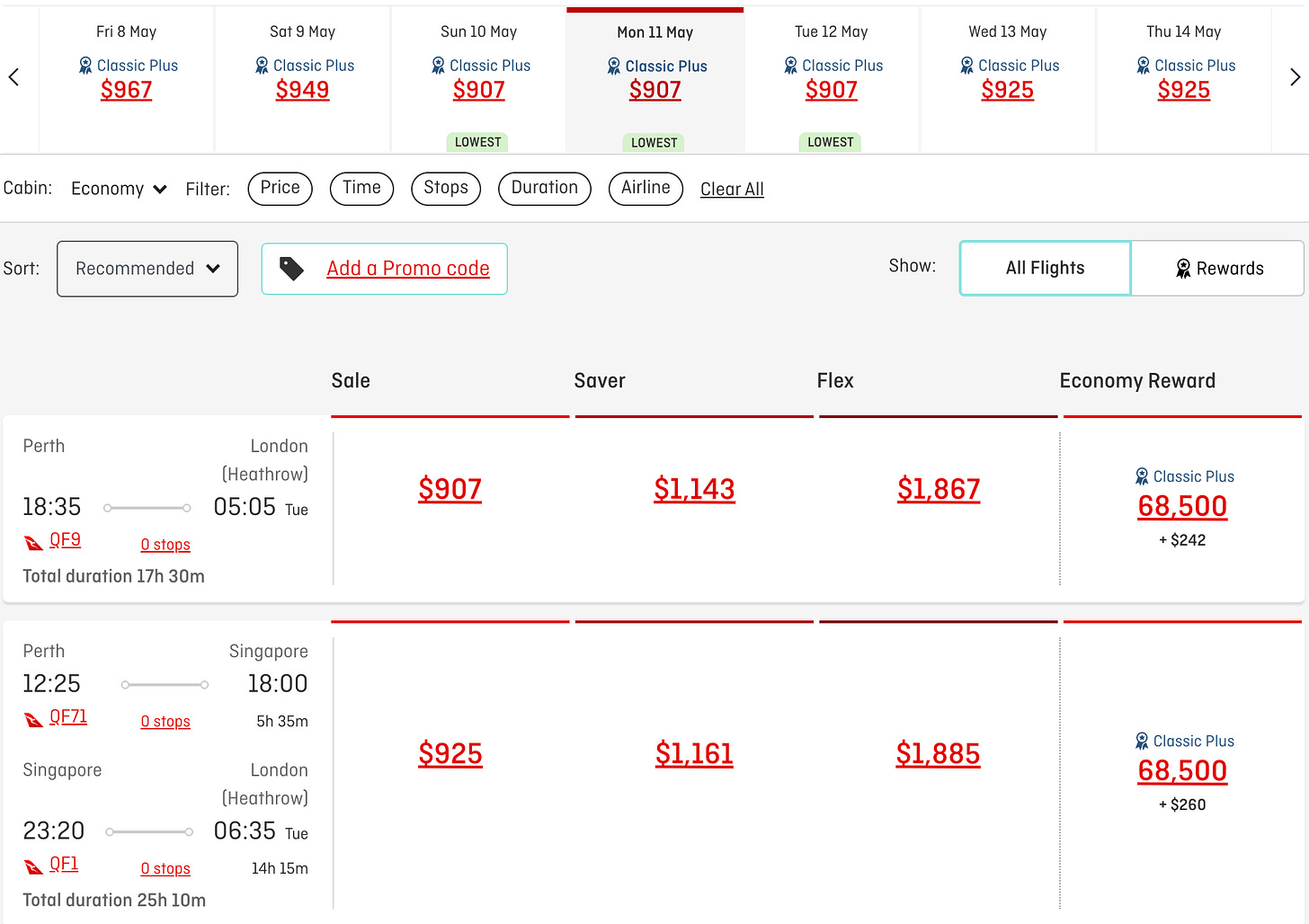

But we digress, back to the point at hand. Let’s consider a practical example of how Qantas prices non-stop and one-stop flights using the existing Perth-London flights, and how it is aims to increase unit revenues, not just yields, on Project Sunrise. Perth-London passengers have two options:

Taking the non-stop Perth-London flights (QF9/10), or

Connecting through Singapore, taking QF71 from Perth to Singapore and then connecting onto QF1 (originating in Sydney); taking QF2 to Singapore and connecting onto QF72 on the return.

Qantas don’t necessarily price tickets higher on the non-stop flight, at least not in economy class. For example, picking a random date in the future we see the non-stop is actually priced slightly cheaper than the one-stop via Singapore. The variance is isn’t due a difference in base fares, but rather the additional airport charges and government taxes for the stop in Singapore. The base fare, i.e. what Qantas is charging, is the same for both the non-stop and one-stop flights.

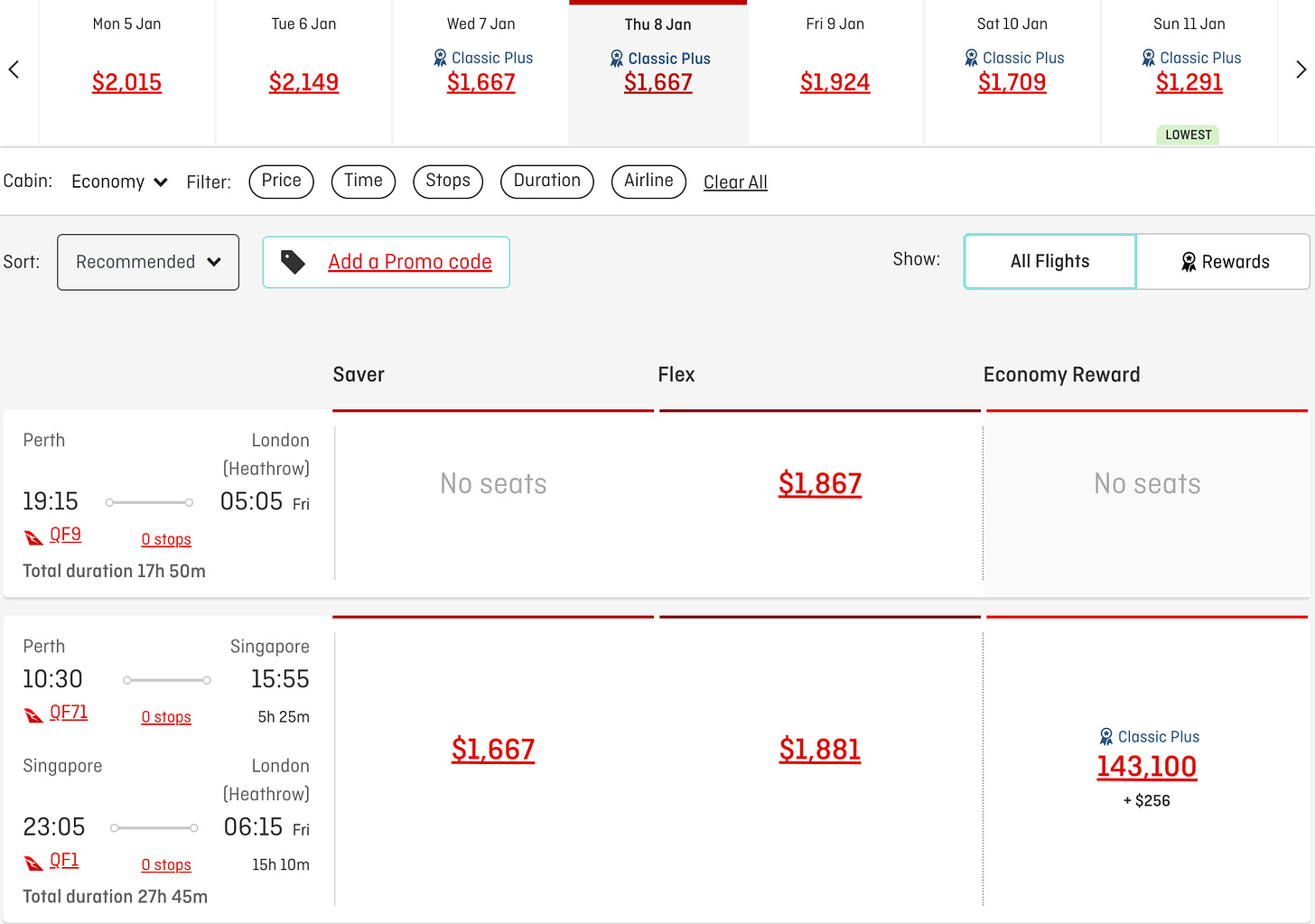

If you bring the date closer, you start to see a variance between the flights with the non-stop flight now more expensive than the one-stop option. Critics might push back at this point, see it’s more expensive! Not so fast!

The fare on the one-stop option is in a cheaper fare class (i.e. saver fare), while the non-stop is a more expensive fare class (i.e. flex fare). There’s a crucial nuance here: the base fares in each fare class is the same. So the prices are the same, but one or both of the following are happening:

The cheaper fares are getting sold more quickly on the non-stop flight, and/or

There are fewer cheaper fares available.

The irony of the 1st point isn’t lost on us. How could that be with everyone on social media telling us they don’t want non-stop flights? Well, it’s always the dissenting voices that are the loudest!

The 2nd point should be obvious since there are simply fewer economy class seats available! Let’s consider this with a conceptual example of a very simplified market and assume Qantas offer three economy class fares of $1200, $900 and $500. These are made-up bullshit numbers, but bare with us:

On the one-stop flight via Singapore, capacity is limited by the smaller A330-200 that flies the Perth-Singapore leg (rather than the A380 that flies the Singapore-London leg). Qantas’s A330-200 has 243 economy class seats. Simplistically, if we assume they sell one-third of the seats at each price point (i.e. 81 seats at each price point), this would generate total revenue of $210,600 and unit revenue of $867 per seat.

On the non-stop flight, they fly the B787-9 that only has 166 economy class seats. If they followed the same strategy of selling one-third of the seats at each price point (i.e. 55.3 seats at each price point), they would generate a lower total revenue of $143,780, but the same unit revenue of $867 per seat.

But why would they do that? If they were able to sell 81 seats at $1200 and 81 seats at $900 each on the A330, then why wouldn’t they just sell 81 seats on the B787-9 at $1200, and 81 at $900, and only the remaining 5 seats at $500.

This is exactly what they would do, and this generates total revenue of $172,600, resulting in unit revenue of $1037 per seat, 20% higher than the A330, and this is the 20% revenue premium!

The smaller economy class cabin means there are simply fewer seats to fill and by filling them from the front they generate a unit revenue! It’s a gross over simplification, but highlights how lower density configurations can generate revenue premiums - in the same cabin - without having to increase ticket prices. As a reminder, Qantas’s A350-1000ULR will only have 140 economy class seats, even fewer than the B787-9, despite it being a larger aircraft!

Analytic Flying is a reader-supported publication, so please subscribe. See our ethical paywall policy to understand if you need a paid subscription (incl. industry professionals and readers using for commercial purposes).

Premium cabins are different though and we would expect to see higher prices for the non-stop flights. For example, looking at the same dates as the previous example, we observe a higher base fares in business class for the non-stop compared to the one-stop flight for the same fare classes. However, these premiums are nowhere near the 20 to 30% quoted earlier, rather about 7% and 9% for business saver and flex, respectively. Premium economy is unavailable on the A330, so there is no point of comparison, while first class isn’t available on either aircraft.

Even in the premium cabins, the revenue premium isn’t generated by higher prices alone, but by smaller cabins. Comparatively, the A350-1000ULR will have 6 first class seats compared to 14 on the A380 that currently flights Sydney-London, 52 business class compared to 80 on the A380, and 40 premium economy compared to 60 on the A380, and 140 economy class compared to 341 on the A380. There’s a lot of scope to increase unit revenue by filling from the front!

Higher unit revenues, but won’t costs also be higher?

In our analysis of the A350-900 and A350-900ULR we noted that the cost of operating them on the same (shorter) route would be similar. Specifically, we highlighted how carrying the same payload over the same distance would burn a similar amount of fuel. We can extend this to the A350-1000 and A350-1000ULR, albeit the ULR will be slightly more costly since it’ll be carrying the additional structural weight of the RCT fuel tank, however we don’t expect this to be very large.

This is a distortion view of the cost dynamics since it only considers "trip cost”. While the trip cost will be similar, the unit cost or average cost per available seat kilometer will be different. Since the A350-1000ULR will seat fewer passengers than the A350-1000, it’ll have a higher than the A350-1000, with the specific magnitude dependent on the configurations of the aircraft.

We don’t know the configuration of Qantas’s non-ULR A350-1000s yet, but it’ll certainly be less dense and have more seats than the 238 seat ULRs. For comparison, British Airways, Cathay Pacific and Qatar Airways seat 331, 334, and 327 on their A350-1000s, respectively. If Qantas follow suit, this would mean that their fuel unit cost of the ULR would be approximately 39% higher than the baseline A350-1000, at least on the same route.

But fuel isn’t the only cost meaning that this cost premium isn’t directly comparable to the revenue premium. In FY25, fuel accounted for 24% of Qantas’s expenditure. If we simply scale this it’ll translate into a 9% unit cost premium, still well below the revenue premium of 20% to 30% that they are targeting, generating a significant boost in margins.

Even then, a 9% higher unit cost might be an overestimate as non-stop flights will generate other cost savings, particularly lower crew costs (single crew working a longer flight is cheaper than two crews working two shorter flights, especially when taking into account the extra stopover), lower airport costs (see the example of the Perth-London non-stop), IROPS costs from additional connection, etc.

While we don’t have a lot of hard evidence to go on here, we can’t simply isolate the cost impact to reduced cabin density. But even if we did, we must consider that Qantas haven’t had to compromise cabin density to the same extent that Singapore have, reinforcing our earlier discussion.

Yet, we’ve also seen Qantas show a willingness to compromise unit costs by employing payload restrictions to enable some of its current ULH routes. Dallas-Melbourne is a good example of this: Qantas operate 4x/week flights, increasing to daily during peak season, operated by the B787-9. This is Qantas’s 2nd longest non-stop flight, however the westbound leg encounters significant payload restrictions due to en route weather. We’re able to investigate this more utilising USDOT data.

Over the last 12 months, Qantas’s declared capacity on the eastbound leg averaged 235 seats, compared to just 225 on the westbound leg (the B787-9 seats 236 passengers). This indicates an average gap of 10 seats, meaning the payload restriction on the westbound leg averaged 10 seats more than the eastbound leg over the last year. For comparison, there was no gap between the east and westbound legs of their Melbourne-Los Angeles B787-9 flights over the last year (excluding those operated by the A380).

There’s a lot of seasonal variation in westbound payload restrictions. There was no gap in October, while the gap remained less than 10 between July and January, however it grew from February to a peak of 22 in April.

The impact of payload restrictions is profound since it reduces the denominator that costs are shared over. An average payload restriction of 10 seats implies a 4% higher unit costs. While this may appear trivial, it highlights that Qantas are willing to tolerance higher unit costs in search of higher yields and unit revenues on ULH flights.

Given Qantas’s recent capacity increases on the route, it is a tacit acknowledgement of the revenue premiums they’re generating from ULH flying. It goes a long way to reinforce their confidence that such premiums are exceeding the marginal cost sufficiently.

But there’s a caveat: on ULH missions, one carries fuel to carry fuel! Simply put, an A350-1000 taking off at 283t is going to burn more fuel over the same route as the same aircraft taking off at a lower weight. Thus, a 22 hour non-stop flight is going to burn, on average, more fuel per hour to carry the same payload than the same aircraft and payload taking a well-timed fuel stop halfway.

But here’s where the A350-900ULR and A350-1000ULR have taken a giant leap forward. Unlike the A340-500, they’re not carrying the same deadweight! As fuel is burned during the flight the aircraft gets lighter, however the A340-500’s excessive structural weight to carry the huge fuel load just didn’t get lighter as the flight wore on.

While this may appear abstract, the fact that the A350-900ULR and A350-1000ULR aren’t meaningfully heavier structures compared to their baseline peers means that they’re more efficient than a previous generation of ULH aircraft. The “delta” to carry the extra fuel for their ULH mission is significantly less than their predecessors.

Project Sunrise isn’t that original!

As our discussion has highlighted, Singapore Airlines have been pushing the boundaries of ULH flying for some time, while Qantas have been doing the same. Project Sunrise will pushing the boundaries further, and significantly so with Sydney-London being 900nm or 11% further than Singapore-New York. Yet, our thesis speaks of it as somewhat inevitable, driven by the technological gains and Australia’s “tyranny of distance”.

While opposing voices will be the loudest, we might look back on this in a few decades as the inevitable evolution from 5-stops to non-stop. And if you don’t like it, then don’t do it. In addition to the plethora of one-stop connecting options, Qantas have indicated that they’ll also maintain one-stop flights to London (via Singapore) and New York (via Auckland).

Many commentators continue to argue that it’s just PR and spin. Yes, Qantas are very, very good at this, but one can’t ignore the technological, regulatory and operational challenges that Qantas have had to, and still need to overcome. They’ve had to order a highly customised aircraft, engage with regulators to reform flight duty limits, and renegotiate employment terms. Nevermind the massive reorganisation of their network that will have to occur (e.g. have a look at our previous analysis on the difficulty in coordinating their existing slot portfolio at Heathrow simply to schedule the Sydney-London flight). This seems like a lot of work, money and risk for a stunt!

So if it’s not about the PR, then what is it?

So far we’ve looked at the technological, operational and economic considerations, but it hasn’t answered the question why they feel compelled to take the risk. These are actually more strategic in nature.

First and foremost, it’s about competition. Qantas’s one-stop flights are forced to compete on price and/or product with other airlines, and in many cases, they’re at a significant cost disadvantage, making it a battle they simply can’t win. This has been a significant contributor to the reduction in their London capacity over the last two decades.

When it comes to Project Sunrise, the competition can’t or won’t do it! This may appear flippant, but it’s at the core of the strategy. Simply put, there are no other airlines that have a fleet capable of non-stop flights between Melbourne or Sydney and London, nor are they likely to.

British Airways are the only other airline with direct flights between Australia and London. They don’t have an aircraft capable of making the non-stop trip and Qantas are making a relatively safe bet that BA won’t suddenly order the A350-1000ULR. Firstly, it simply doesn’t make sense for BA to acquire the niche aircraft on just one route. BA won’t have the scope to build scale over several routes and there aren’t many other 22 hour routes from London that BA would want to fly that would enable them to build a fleet of A350-1000ULR aircraft. Secondly, even if they were to do so, Qantas have the first mover advantage, reducing the likelihood of BA doing it.

The same factors also apply to Virgin Atlantic (or Delta UK as some might tease), who have shown little interest in recent years beyond Trans Atlantic flights or flights that benefit from Joint Venture feed. The other Virgin, Virgin Australia are only operating long haul flights on wetleased aircraft at present. They are a long way away from returning to their own long haul operations, nevermind trying to operate a niche sub-fleet of ULH aircraft. It could take a long time before Virgin could even consider it, and more to operate it if they wanted to. It would appear as thought Project Sunrise would give Qantas a monopoly on non-stop flights to London, and probably to Western Europe as well.

A similar case can be made to the US. Are United, Delta or American Airlines going to acquire a special fleet simply to operate non-stop flights to Australia? Again, the question would be are there other ULH routes that may interest them to build scale around an ultra long haul business? The scope is a little broader for the US carriers, but despite their growing international ambitions, there have been no suggestions that they’re interested in it. US carriers haven’t attempted to cover Singapore’s New York routes, and there’s no indication that they’d do the same to cover Qantas’s New York route.

The lack of (potential) competition on non-stop routes gives Qantas an advantage that competitors can’t match, or at least are unlikely to. In fact, Qantas’s most significant competitors to London aren’t BA or Virgin. It’s the one-stop options, primarily Emirates, Qatar, Singapore, Cathay, etc.

The most recent market share data between the Australia and UK shows Qantas and BA with just 20% and 5% of the market, respectively. The remaining 75% is held by one-stop carriers, led by Emirates, Qatar and Singapore with 23%, 17% and 12%, respectively. It’s this 75% that Qantas are targeting with near certainty that they’ll have a monopoly on non-stop flights between Australia and the UK!

In addition to the strategic advantage, the lack of competition brings two practical advantages. Firstly, pricing power, allowing Qantas to generate higher yields and unit revenue, particularly from the front cabins, but secondly reducing the need to discount to attract or defend market share!

At the same time, Qantas are being rewarded for their patience. While Singapore got to market first, Qantas’s patience means they entering the stage with a better solution and considerably lower risk. A dalliance with the the A340-500 would’ve cost Qantas a lot of money and set them back a long time. The evolution to Project Sunrise isn’t a zero risk strategy, however they’re not facing a catastrophic scenario if things don’t go as planned. The aircraft will simply be converted into a regular configuration and fly on across the rest of the network.

But really, why are they doing it?

By this point it’s taken a lot of convincing and not everyone would be convinced by this argument. Despite the relatively lower risk compared to a decade or two ago, it’s still a risky endeavour. We’re made the operational and strategic case, but it still involves a leap of faith. These arguments don’t explain why Qantas feel they need to take the risk. They’ve have had a run of incredibly strong results, so why now?

We titled the article “how to think, not feel about Project Sunrise”, yet the question we pose now asks “Why does Qantas FEEL compelled to take the risk?”. We’re on shaky ground here, so one final point of analysis to nail the argument:

Qantas’s international operations are the worst performing part of the Qantas Group. This isn’t a shot at Qantas International and shouldn’t be misinterpreted as an argument that they’re performing poorly, rather it’s an empirical point that Qantas International is lot less profitable than Qantas Domestic and Jetstar. This relative profitability within the group has implications for capital allocation.

In FY25, Qantas International contributed just 25% of airline EBIT (earnings before interest and tax), despite accounting for 41% of airline revenue and capacity (measured by available seat kilometers). We’re referring to airline EBIT and revenue, so stripping out the non-airline parts of the business including Qantas Frequent Flyer and corporate.

This isn’t a recent trend and Qantas International didn’t suddenly have a poor year. In fact, FY25 was a very good performance, as the years leading up to the pandemic saw its share of airline EBIT consistently lagging its share of airline revenue and capacity, and by even wider margins in most years.

Some commentators argue that Qantas International’s profitability is undervalued given its importance to Qantas Frequent Flyer (QFF). QFF is an immensely profitable part of the group, earning A$ 556 million in EBIT during the last financial year. Let’s humour this for a moment: if we generously add all of QFF’s EBIT to Qantas International, it would contribute 39% of EBIT, broadly in line with its share of capacity (41%). However since QFF’s revenue is also now included, the share of EBIT is still lower than the share of revenue that now stands at 47%. FY25 is consistent with historical trends, including the periods before the pandemic.

Thus, it would require the most generous assumption for Qantas International’s performance to even be comparable to the rest of the group, highlighting a clear underperformance of Qantas International. The reason for this is fairly simple: Qantas International faces a lot more competition compared to the Qantas Domestic as the domestic market faces larger barriers to entry. While this is somewhat beyond the scope of our analysis, the implications are relevant.

At a group level, it’s not rational to disproportionately deploy capacity - and thus capital - towards the least profitable part of the group. In the long run this has the potential to drag the rest of the group down with it. This is particularly consequential for an airline given the highly capital intensive nature of the business. Again, this isn’t the focus of our current analysis, but have a look at our previous work on the topic to give more context why this is so important:

As noted, Qantas International’s relative underperformance isn’t a new phenomenon, and it’s arguably already had consequences for the group’s capacity allocations. Qantas International accounts for 41% of ASKs, down from 46% in FY19. However, if we go back even further back, Qantas International accounted for 77% of group ASKs in FY01 (it’s the furthest we could quickly find). It’s a different baseline (i.e. no Jetstar), however it clearly shows how Qantas have steadily “underinvested” in Qantas International’s capacity.

This shouldn’t be interpreted to mean that they’ve marginalised the business, rather the more profitable parts of the business have attracted capacity more rapidly. And before anyone quips that Qantas International’s poor performance is due to this underinvestment, let’s remind readers that we’re not using the term in an absolute manner, rather relative. In fact, Qantas’s mainline fleet is slightly younger (average age of the A330, A380 and B787 fleet is 15 years) than the domestic mainline fleet (average age of the B737 and A321 fleet is 17 years).

My head is spinning right now, so can you pull it all together now?

So here is our hypothesis: Qantas is in the early stages of an extraordinary and near total fleet renewal. With the exception of the B787s and a handful of newly delivered A321XLRs, every mainline aircraft will be replaced in the next decade. The order book already includes replacements of all B737s, A330s and A380s, with the bulk of the B737s and A330s being replaced within the next 6 years.

The relative performance of Qantas International makes the business case for this investment relatively weak compared to Qantas Domestic and Jetstar. To justify this incredible capital expenditure, Qantas International has to make a deal with the devil by increasing its margins, and by a lot! If it’s unable to do so, the board will have little option but to continue the relative underinvestment in Qantas International, limiting their capacity growth or even shrinking capacity.

Arguably, the A350-1000ULRs have been ordered to provide incremental capacity growth as they’re not replacing an existing fleet, at least for the time being! The rest of the order book is replacement capacity: the A330s will be replaced by a confirmed order for more B787s and A350-1000s (non-ULR version). However, it’s notable that the A380s, which are due for replacement from 2032 or thereabouts, don’t have confirmed replacement orders. While Qantas have confirmed that the A380s will be replaced with more A350-1000s, these orders aren’t confirmed (at least based on most recent AFS) and will utilise purchase options that were part of the previous orders.

A “deal with the devil” means making a risky and morally questionable agreement with a powerful or dangerous entity for personal gain.

And this is Qantas’s failsafe: if Project Sunrise doesn’t live up to expectations and if Qantas International are unable to increase margins significantly between now and 2032, or at least show some evidence of their ability to do so, the Board won’t hear a convincing case to exercise the options to replace the A380s. Instead, it’ll make more sense to limit Qantas International’s growth, or maybe even reduce capacity or shift capacity to Jetstar or joint venture partners, all things they’ve done in the recent past. Instead, the A350-1000ULRs could/would become the de facto A380 replacement.

In the introduction, we pointed out that Cam Wallace, the CEO of Qantas International, initially wrote-off Project Sunrise as a publicity stunt. So we wondered what changed Cam’s mind? We think Cam was convinced that Qantas International needed a paradigm shift to increase margins and maintain its relevance within the group. Gimmicks and small changes weren’t going to drive the structural shift needed in margins.

Project Sunrise is a paradigm shift! But it’s also a bet, a big bet, that they can increase margins by shifting a significant portion of capacity to routes with limited competition, allowing them to gain pricing power and exploit lower density cabins to increase unit revenues (doing so significantly quicker than unit costs will increase). Moreover, it does this with a relatively low risk failsafe! While it’s not zero risk, it’s not taking on same degree of risk that Singapore and Thai did with the A340-500.

Analytic Flying is a reader-supported publication, so please subscribe. See our ethical paywall policy to understand if you need a paid subscription (incl. industry professionals and readers using for commercial purposes).

Now before you think it’s too fanciful, we’re not trying to suggest that this was a grand strategy plotted in a smoke-filled room more than a decade ago. Instead, Qantas International faced a challenge: develop a strategy to increase margins to justify their capacity! They were simply sick and tired of seeing the relative investment in Qantas International declining over time.

The problem that lead them down the path is there aren’t many things that can systematically increase their margins. They’re already exceptionally good at generating strong yields and competition limits their ability to increase this further without increasing costs quicker. Frankly, they’re already a pretty efficient operation. It’s not like there’s a trick they’re missing on the cost side. No doubt, everyone has their pet idea, something that they think can improve margins, but Qantas recognised the need for a paradigm shift, rather than small ideas.

While the idea isn’t novel, the relative success of pushing the envelope with the B787 on ULH routes like Perth-London, Melbourne-Dallas and Auckland-New York, has convinced them that the concept works. They’ve seen the data and it shows them the secret sauce: increasing unit revenues quicker than costs increase, thereby increasing margins. It’s reinforced their confidence that this will also be the case from Sydney and Melbourne, non-stop to London and New York!

It was just a matter of when to roll the dice. They remained patient, waiting for the technology to find the sweet spot where they could do this without risking the whole show! They’ve eventually found their aircraft and pulled the trigger!

Hopefully this provoked you more about how to think, and not feel about Project Sunrise! Thanks for reading, and please share it with colleagues and friends!

I really appreciate how much time and effort you put into this detailed analysis!

I would love a complimentary article about how the new Perth Hub can work as a margin and capacity boost to QF international business, like PS.

Fascinating piece of analysis.

A couple of technical points:

- It looks as if you are assuming that Qantas will route the Sunrise aircraft to London westbound. That is certainly the shorter great circle distance (by around 800nm). But from a series of 2017 Leeham articles, with input from Qantas, it seemed pretty clear that the London route would usually be flown eastbound and over the pole (imagine a waypoint around Anchorage) to take advantage of the prevailing westerly winds. The Leeham analysis said that, using this and other techniques to maximise range, the flight planning distance for Sydney-London could effectively be capped at around 9500nm. Here's the link (paywalled): https://leehamnews.com/2017/06/29/qantas-ultra-long-haul-dream-part-2/

- Then there's the ACT. I think Qantas (the PR team?) is making mischief with the term "rear centre fuel tank". They are familiar with the RCT because it's in their new XLRs. But apart from their use of the term I have seen no evidence that Airbus has engineered an integral tank similar to that in the XLR. In the case of the XLR that involved a substantial design, engineering and certification effort. Airbus released photos along the way and there was extensive reporting around the certification issues. We have seen nothing that I'm aware of pointing to development of a modified rear fuselage to build in an integral tank into the A350-1000. Unless someone has evidence to the contrary I'm assuming this is just a case of Qantas deciding they don't want people to see pictures of a big ugly 20,000l spare gas tank at the front of the hold.