Technical Thread #4: Qantas's Sunday morning IROPS masterclass

This last Sunday morning (23 November 2025), poor weather along the eastern seaboard of Australia resulted in major travel disruptions. The weather had a significant effect on inbound arrivals from the United States, resulting in several technical stops and diversions.

This short article outlines a technical thread we posted on social media on Sunday morning, highlighting Qantas’s IROPS masterclass! We thought we’d repost it here with a little bit more detail to work through the IROPS challenges and implications, and quite frankly, just how well they responded!

Additionally, our post was plagiarised, word-for-word, by at least one publication. We wanted to post it here to ensure our analysis was documented. As we’ve noted before, it’s why we’re considering placing our work behind a paywall and promoting the use of an ethical paywall.

Background

Thunderstorms at SYD and CBR meant QF22 DFW-MEL had to take unscheduled fuel stop at AKL, while QF12 LAX-SYD and QF8 DFW-SYD both diverted to BNE. Why does SYD and CBR weather force MEL bound flight to stop in AKL for fuel you ask?

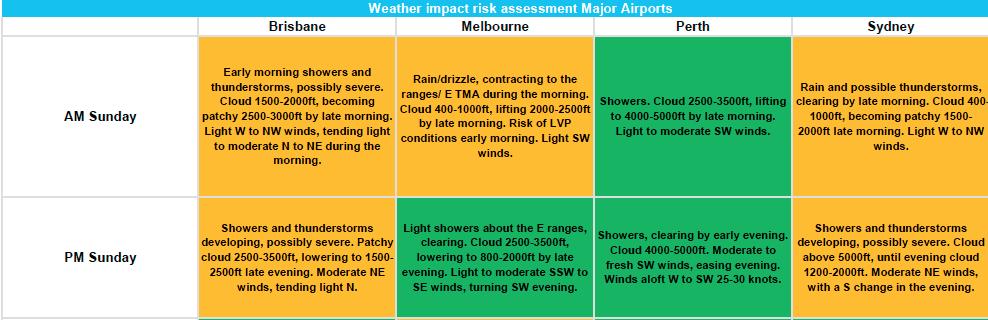

Poor weather was forecast on Sunday morning at Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney, as highlighted in the daily ATFM plan published by Air Services Australia. The forecast wasn’t catastrophic, however it included the chance of thunderstorms at both Brisbane and Sydney. A particular challenge with thunderstorms is their localised impact, while their exact timing and location can be difficult to predict. This makes planning flights around thunderstorms difficult with a lot of uncertainty.

QF22 DFW-MEL

QF22 DFW-MEL, operated by a B787-9, made an unscheduled fuel stop at AKL. It seems obtuse that thunderstorms at SYD and CBR meant a flight to MEL needed to stop along the way for fuel, however QF22 couldn’t use SYD or CBR as their alternate since poor weather was forecast. For flight planning purposes, one needs good weather at your alternate or a 2nd alternate further away with better weather.

This meant that QF22 needed to carry extra fuel for an alternate further away, however the flight is already carrying a significant payload penalty and pushing physical fuel carrying capacity. It’s one of the longest flights in the world and already operating at the edge of the aircraft’s capability.

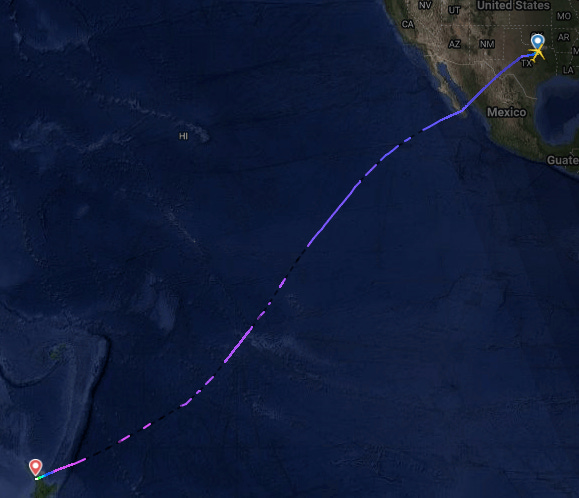

It’s likely that QF22 simply couldn’t carry any more fuel, or would’ve required a catastrophic payload penalty to carry fuel the additional fuel required. Instead, QF22 was replanned to depart DFW for AKL. The ADS-B data clearly shows the aircraft heading directly for AKL after departure.

Taking a tech-stop at AKL generates several externalities as crew will exceed their duty limits and time out at AKL. It’s not like airlines just keep B787 crew hanging out at AKL just in case. While Qantas do operate B787 flights to/from AKL, it’s not a B787 crew base. This meant that an alternative crew had to reposition to AKL. This may have occurred ahead or time, or possibly the crew was switched with QF3/4 (SYD-AKL-JFK flight).

ACARS messages show significant care to mitigate passenger disruptions. For example, this included arranging catering for additional leg in the middle of the night and rebooking of connections. We really loved this one:

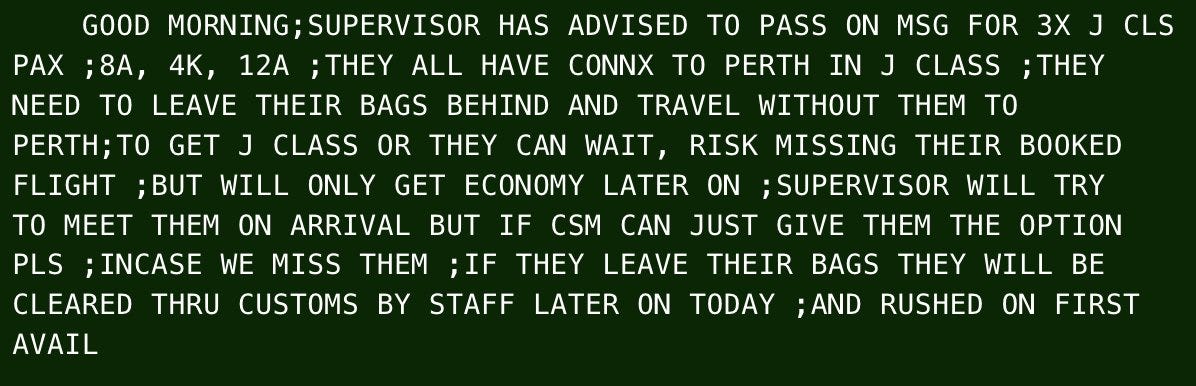

Onward business class passengers from MEL to PER were given option of rebooking on immediate onward connection without their bags, or a later connection with bags, however this would be in economy class due to limited seats available on that flight. Furthermore, the message gives a clear indication that ground staff were prepped to help, but also giving passengers autonomy to make decision!

All in, they arrived at MEL just short of 3 hours late which is good going for unplanned stop which required crew change! But that’s not all …

QF12 LAX-SYD

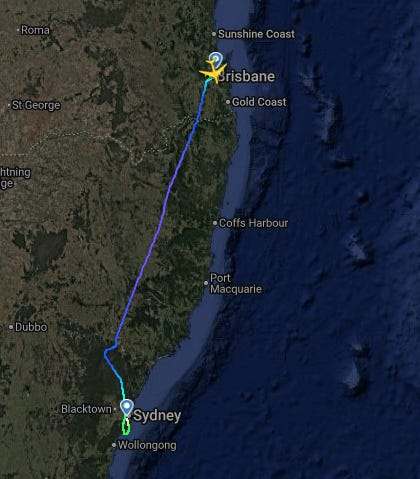

QF12 LAX-SYD, operated by an A380, diverted to BNE. Unlike QF22, this decision wasn’t planned ahead and a relative late decision was made a few hours out of SYD. This is obvious from the ADS-B data which shows the flight clearly heading to SYD.

Weather at SYD was somewhat worse than expected with the thunderstorm expected over the airfield near landing time which would’ve required significant additional holding. Waiting that out at SYD would’ve risked landing below minimum fuel or encountering a fuel emergency.

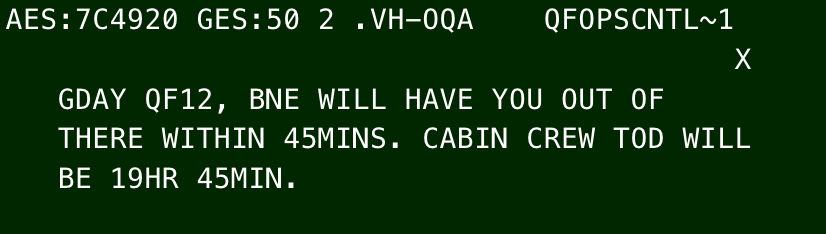

The diversion to BNE was ostensibly for fuel, however the much shorter length of the flight compared to QF22 meant that if the aircraft were refuelled quickly they could continue to SYD without exceeding the crew’s duty limits.

No crew had been repositioned and there was a significant risk of hitting duty limits. If the aircraft wasn’t refuelled quickly it would’ve required termination of the flight at BNE.

Once again, ACARS messages show s sense of urgency with ground crew prepped to hustle for 45 min splash and dash. That’s clearly aspirational since it was very unlikely to turn an A380 that quickly. Nevertheless, they managed to get out of BNE in time and made it to SYD a little over three hours late.

QF8 DFW-SYD

QF8 ran into similar troubles to QF12, with an even later decision to divert to BNE. Also operated by an A380, QF8 has a longer block time than QF12 meaning that it was inevitable that the crew would exceed their duty limits as a result of the diversion.

As a result, the flight was terminated at BNE and passengers rerouted to their final destination on domestic flights from BNE. The aircraft ferried empty to SYD later that day.

BNE isn’t an A380 crew base and with no relief crew available at BNE it highlights how the proactive decision to replan QF22 to AKL limited the impact of diverting like QF8 did.

Concluding thoughts

In practice, managing IROPS is incredibly challenging. While an individual passenger is focused on their flight, staff at Qantas’s integrated operations centre are handling multiple flights simultaneously. Three flights took unscheduled stops or diverted, but the same attention would’ve had to be applied to countless other flights that didn’t stop or divert.

Furthermore, the environment is dynamic with parameters changing constantly as evidenced by the situation devolving through the night while the flights were already in the air. This is evident by the examples, highlighting how different flights encountered different constraints (e.g. flight duty limits affected each flight differently).

It’s all good having great IROPS plans and procedures in place, but implementing them in a dynamic and evolving environment is difficult, especially when resources are limited. Airlines simply can’t have unlimited redundancy (e.g. it was possible to plan for crew redundancies on the B787 at AKL, but not for the A380s at BNE).

No doubt a lot of passengers will be irate, but this is as good as it gets! There’s no better outcome here, just much poorer outcomes. The public doesn’t get to see what happens behind the scenes. They don’t see how decisions - invariably focused on the least worst outcome rather than an optimal outcome - get made under pressure with imperfect information.

But this isn’t the public’s fault. They aren’t technical experts and we shouldn’t expect them to see the big picture. They will inevitably focus on their flight and the impact on their plans!

We can’t ignore that airlines don’t do a great job at communicating just how complex and difficult this is! Actually, they do a terrible job often dumbing things down and being incredibly vague, and Qantas are far from the worst!

As we’ve argued before when analysing the potential impact of flight delay and compensation schemes, it often appears to the customer that the airline is hiding information or not being truthful.

Airlines are simply too scared to say too much. A culture of risk aversion dictates that they mustn’t say anything that the public may use to hold them to account. So instead they’ll say vague things like “your flight is delayed by weather”. It’s true, but is infuriating to hear because it’s obvious.

Why don’t more they communicate more transparently? Do they think people don’t want to know, don’t care or can’t understand? We’re not suggesting a sinister motive, rather just risk aversion, but we argue that transparency builds trust and shows customers that they’re not the victim of a random bureaucratic decision.

This was a great opportunity for Qantas to communicate the challenges that running an airline encounters and just how professional their handling of it was. It was a masterclass!

I was on NAN-SYD in May last year, connecting to Perth, and we were an hour late out of NAN due to late arrival of the inbound aircraft, which cut my connection down to just 45 minutes - onto the last service to Perth. Qantas were fantastic. They called ahead to SYD when we got within range, got us moved to land on the main runway to reduce the taxi time to the terminal, and got the Perth flight held so we could make it. The CSM came around and spoke to all PER pax (there were 11 of us) and gave me super clear directions for where to go when I exited customs (I have never I/D same day transferred at SYD before, so wasn’t sure) and without her instructions, I 100% would’ve gotten lost. It took a fair bit of sprinting, but with all the coordination, I made the connection and so did the other 10 pax!